Four days on the road to Quito

Feb 14, 1975

We Left Guayaquil in the rain, over the bridge again and back along the same road to El Triumfo, a busy, muddy cross-roads with roadside stalls selling bananas, pineapples, small mangoes, and muddy-looking juice. Bought two pineapples for 4 sucres (7p). These stalls always look crammed with a variety of foods until you look closely – also striking how hard it is to get vegetables in the countryside.

Passed some enormous banana plantations – kilometres long. Thickest, lushest vegetation I’ve seen. Then the rapid rise into the Andes again, and soon we are up to 2,500 metres, but the hills here are smoother than in Peru, the countryside more ordered, better worked, with some large houses. Had the idea of being invited at a hacienda and chose a large white house, below the main road, to the right shortly before Riobamba.

Met in the yard by a peon (but in Western clothes) who invited us to sleep inside. Building seemed deserted. In fact it is used as a school (one room) filthy and bare, as was our room. B wanted to use the hammocks, and pulled up a gate post, under the appreciative gaze of the custodian and his family – an Indian woman and tots. The post went on the windowsill against the steel frame windows. Another post went inside the cupboard, diagonally across the room and the hammocks were slung between them. Four eggs lay in some grass in the cupboard.

The Indian woman with her tots

We asked if we could buy some food – eggs or meat. They said there was a tienda (shop) cercita (nearby) down the road. We decided to walk there and we walked forever down the hill and eventually met the custodian coming back on his horse. He pointed out a house and we asked for a chicken. They were dubious at first (three men and a woman) then tried to decide which bird to sacrifice. At first they went for a cock but it was too expensive so we settled on a mottled pullet for 50 sucres and had a fine chase all around the yard to catch it.

The walk back took me over an hour. It would have been shorter if I had been as enterprising as Bruno and caught the back of a passing bus. I tried to wring the chicken’s neck and failed. B chopped the head off with his machete. The family plucked it, I gutted it, and we boiled it. It was a stringy bird but the legs were tender. The family also gave us a plate of pork, but it was too much after all for one meal. There was still the chicken’s carcass in the pot.

Feb 15

Woken in the morning by a hen at the window, anxious to get to its nest and bewildered by the change of scenery. It stood on the windowsill observing us from every conceivable angle and clucking. At last it managed to edge its way along my hammock and with much floundering and shattering made its way to the cupboard, but failed to lay.

Before leaving I at last took the trouble to examine my rear axle. The bike had been wobbling strangely since Lima where I had aligned the wheels (i.e it was much worse than before when the wheels had been really out of line). Found to my stupefaction that both spindle nuts were loose and presumable had been for 1000 miles or so. What I get away with! Terrifying what omissions I’m capable of. Got the wheels straight and tight, and of course the wobble is no more.

Getting out was an ordeal for Bruno. His van couldn’t make the climb up the dirt path. He had to take a series of dives from off the road to get enough speed up but eventually he got out.

Riobamba was a pleasant town. People seemed more relaxed here – less aggressive. Many plazas, a few nice buildings, a nice working market, helpful shopkeepers, little attempt to sell things to us. Went on until dusk when I found an inviting field by the side of the road. Children all said we should stay there, so we went in. Then adults arrived. Owner’s wife and her sister. Sister was very inquisitive and aggressive but invited us in to talk. They were enraptured by Bruno, gasped at his exploits, plagued him with questions and took no notice of me at all. For me a very unusual evening since I have become used to being the focus of curiosity and attention. Most of all it astounded them that he insisted on sleeping out. They were sure he would freeze to death, and I thought he’d find it chilly (he did).

Bruno and his audience

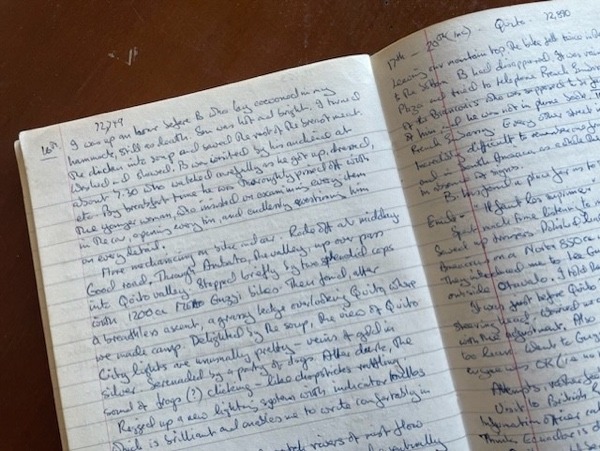

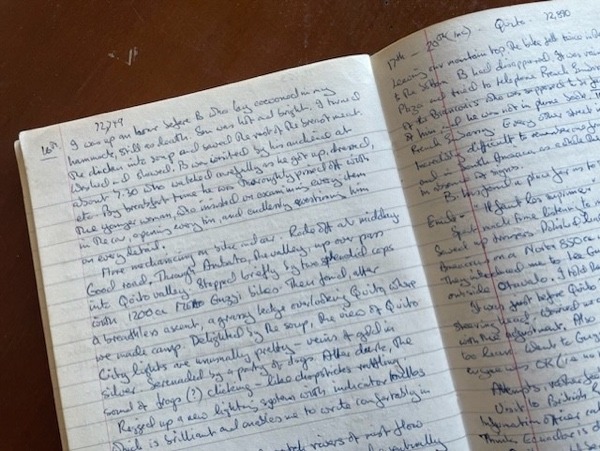

Feb 16

I was up an hour before Bruno, who lay cocooned in his hammock, still as death. The sun was hot and bright. I turned the chicken into soup and saved the rest of the breast meat. Washed and shaved. Bruno was visited by his audience at about 7.30, who watched carefully as he got up, dressed, etc.

By breakfast time he was thoroughly pissed off by the young woman who insisted on examining every item in his car, opening every tin, endlessly questioning him on every detail.

The road to Quito was good and we made good time. Crossing through Ambato into the Quito valley we were both stopped by a pair of splendid cops mounted on shiny 1200cc Motoguzzis, but after a short period of mutual admiration, we went on to find ourselves on a pleasant grassy ledge above the capital.

Comforted by the chicken soup I had made that morning, we looked down on city lights which were unusually pretty – veins of gold in silver. A party of dogs serenaded us, and after dark a sound like chopsticks rattling which we thought must be frogs. I was particularly pleased with a new lighting system I had rigged up using indicator bulbs – brilliant, and allowed me to write in my tent.

Just before going to bed we watched rivers of mist flow down and engulf the city. Then came a chorus of distant shouts, sounding like a political demonstration. The P.C.M.L.E (Partida Communista Marxista Leninista de Ecuador) was busy agitating for oil nationalisation without compensation to ensure a bright future for everybody. But it turned out to be a football crowd.

Feb 17

Bruno hoped that some French volunteers in Quito would put us up, so the following morning in light rain we went down to the city. Well, I slithered down, and went over twice in the mud.

By the time I got to the bottom Bruno had disappeared. I found the central plaza and tried to find the friend of a friend who was supposed to be famous, but nobody had heard of him, and he wasn’t in the phone book.

It took me two hours to find Bruno at the French Embassy. Every other street in Quito is named after a date – incredibly difficult to tell one from another – and in South America the traditional revolutionism is reflected in an absence of signs.

Bruno did find a place for us both to stay, with Emile and Claude, who also had a gramophone, and we spent half a day just playing, again and again, at top volume, the overture to Tannhäuser. Our conversation with the two volunteers was inevitably about our experiences and frustrations. Emile had not benefited by his time in Ecuador and thought its inhabitants should be put down. “Il faut les supprimer.” After a while we realised he wasn’t joking, which made us uneasy.

Bob and Annie, from California on their Norton

The following day, riding around Quito, I came across an American couple on a Norton 850. Of course we stopped and talked. Bob and Annie were from California. They told me about a hacienda near Otavalo where we would be welcome. They were on their way to Cuzco and I told them to take the road from Huancayo. They introduced me to Lee Guzman and his garage, where I took up the play in my steering head, and changed my 140 jet for 150, 140 being too lean.

Quito would be a pretty city in better circumstances – nice buildings, plaza, etc – but rain too heavy for appreciation. Next day we leave for Otavalo.

I’ve been reading my old notebooks again and enjoying the memories. There is so much that never made it into the book. Sometimes the story is written out in enough detail so that I could lift whole episodes straight onto the computer as I did a couple of weeks ago, with the story from Sri Lanka. At other times the notes are very brief but I can reassemble the story from memory. That is the case with my visit to Gauyaquil.

Forty-eight years ago this week I was still travelling in the company of Bruno, a young Frenchman with a much-battered white Renault van. His own companion, Antoine, had left him to fly back to Paris from Lima. Now we were making our way up the coast of Peru towards Ecuador and we had just spent two glorious days on a perfect beach, feeding off the sea.

Without the fish the impoverished people living on this arid coast could not survive. It never rains and water has to be delivered by tanker. But the sea off the coast of Peru was said to be among the richest fishing waters in the world, and we took full advantage.

Not that we caught anything ourselves, for all our efforts, but two fishermen who had brightly painted boats anchored there were happy to sell us a big, beautiful sierra and another fish they called a lenguada which we grilled and ate with tea and cigarettes.

The beach was scarcely visited but as I was packing up to leave three men and a woman came down to the sea. I was some distance from the water’s edge, just able to see their faces, and I saw the men ducking the woman in the water.

She was fully dressed in a short black skirt, a yellow blouse and a pink scarf round her hair.

She scrambled out of the water and appeared to be laughing, but they threw her in again. I went on packing but every time I looked up they were doing the same thing and as I rode off the last thing I saw was the men throwing the woman into the sea again. Needless to say I felt uneasy.

SAN JOSÉ, PERU

It took us two days to reach the frontier with Ecuador, passing through an oil field at Tumbez where we ate enormous oysters, and suffering a hot, sticky mosquito-ridden night at Puerto Pizzarro on our way. The border at Aguas Verdes was extraordinary – quite unreal. On one side, everything was dry as bones: on the other side a profusion of humid vegetation as though nature had conspired to create this barrier between two nations. Thick banks of tall grass interspersed with banana trees extended from the roadside into the surrounding hills, making any thought of camping difficult, and rising up from the grass, here and there were wooden houses on stilts, some quite lovely, all wreathed in air misty with moisture.

The road left the coast and climbed up into the Andes again, but there were wearying police controls, six of them, before we got to Durán and the bridge that took us back down to the coast and the important port of Guayaqil.

Quite why we went there escapes me now. Perhaps Bruno was hoping to do something useful with the French consul. We found a hotel that rejoiced in the name of a five-star Parisian hotel, the Crillon, but there the resemblance stopped. As I entered my room I heard the stampede of cockroaches making a dash for the shadows, and the ceiling plaster over the shower had fallen away to reveal the plumbing of the shower above. Even so, with the help of a Sanyo Widemaster fan I spent two nights without too much discomfort.

Before leaving England two years earlier a friend who was also an Olympic yachtsman had told me that if I should ever find myself among sailors the mere mention of his name, Tony Morgan, would guarantee that they would take me to their hearts. I noticed on a folder for tourists that there was a Yacht Club in Guayaquil so in the afternoon we trod the boards of the port to find the massive carved door of the club firmly shut. I persisted, ringing and knocking, until a porter came to open it, and I explained that I wanted to meet some yachtsmen. He appeared to be bewildered and it took him a minute to register. Then he said, “Señor, there are no yachtsmen here. Nobody sails. They only come here to drink.”

We were equally disappointed in our efforts to find the beautiful part of old Guayquil promised by the tourist flyer, and after tramping around some mouldering but far from charming neighbourhoods we thought we would at the very least find the lobster that had eluded us since Lima. We found a restaurant with lobster on the menu and paid a rather high price for lobster that was not especially good. Furthermore, there was no wine. It must have been all these disappointments that made me particularly vulnerable. When a boy of about 12 came to the table to offer me (and it’s interesting that he chose me and not Bruno) a bottle of Dubonnet at an absurd price. At first I laughed at it, but as the price began to come down to something almost reasonable my scepticism dissolved in the pool of my greed and I bought it. As soon as I’d given the boy the money I opened it. The seal was in perfect condition, but by the time I’d tasted it he had gone. It was a bottle of vinegar.

I was mortified by my gullibility, but Bruno was outraged. He dashed out of the restaurant and seizing two of the boys always loitering in the streets he charged them with the job of finding the miscreant for a reward and sent them off in opposite directions. They came back after a while and both said they’d found him, but one was more credible than the other. Bruno followed him, but instead of a boy he found himself facing a man who looked so villainous that Bruno decided justice could wait for a more worthy object.

The following day we met a man who thought our “wine” was delicious. But that’s another story.

Last Sunday I joined a small group of bike riders on Zoom to talk about depression, not everyone’s favourite subject but a difficult one to ignore. I met with Eva Strehler, who is translating my latest book into German, and Claudio Gnypek, who was recording the meeting for a podcast, but the main man was Dieter Schneider. Dieter is in his youthful sixties but he had a son who suffered from depression and committed suicide, an unimaginable tragedy no less awful for being one of many thousands.

He found he couldn’t simply accept it. He felt he had to do something, and after long journeys looking for a solution he appealed to his friends to join him in a ride, to focus attention on the problem. He discovered, of course, that he was far from alone, and his ride is now a regular thing with hundreds of bikers taking part. He thinks of it as a fellowship and calls it the Fellows Ride. There is even a film going the rounds in Germany.

I have never been depressive and like most people, however deep in the dumps I might be, I can generally find pleasure in just being alive. But in my early life there were aspects of my personality that I did find depressing. I was self-conscious to a fault, convinced that I was always being judged and found wanting. I went to unnecessary lengths to please, and I was timid in the face of authority. I rehearsed all my important meetings ahead of time and never really learned to think on my feet. I was quite aware of all this and it sickened me, but I couldn’t overcome it. I relied almost entirely on my intelligence to make progress in life.

My big journey, the one that crystalised out as Jupiter’s Travels, changed all that, even though the change was totally unexpected. It never crossed my mind that the journey would have any effect on me. I was driven by curiosity, not self-improvement, and yet the effect it did have on me was life-changing. I have spent a good deal of time since trying to extract from the experience the elements that brought this about and released me from my earlier inhibitions.

First of all, I was alone, with nobody to judge me or help me or take over. I was on a machine that I had only recently learned to manage, and only in quite easy circumstances. I knew that, as a novice, I was in danger and that the danger would increase as I moved into ever more unfamiliar surroundings. Inevitably there was always a degree of fear to overcome, and I found a way to work with it and learn from it.

Then there was the machine itself. I had only basic mechanical knowledge, a few tools and a workshop manual. I had to keep it going, meaning I had to learn about it, be aware of it all the time, check it out every night looking for problems. It was all I had for the next 50,000 miles.

The travelling itself was demanding; finding shelter and food, managing currencies and borders, learning the rudiments of languages, learning how to avoid accidents, and of course keeping notes of everything. And to balance against all this drudgery was the sheer excitement of it all and, at first, the wonder that I was actually able to make it all work, that it was really me here in the desert where I once as a child read about Rommel’s Afrika Korps battling with Montgomery.

There was no time or reason to think about I how looked; I was unique, a traveller on a motorcycle, a phenomenon and I set the standard. Who would care how I was dressed, whether I was clean or dirty, shaven or bearded. So I soon forgot about myself and found that I could see others much more clearly. And all those hours alone with myself inside my helmet? They were busy with thoughts about what I had seen and what lay ahead, people I had met, the scene I was passing by and how I would describe it.

What I am trying to demonstrate is that I was so physically and mentally stretched by the enterprise that there was no room for negative thoughts about the meaning of life. I am convinced that by being voluntarily exposed to great physical and mental effort I defeated my old mindset.

I am afraid this may all sound naïve and boastful. Would it be impossible for someone suffering from clinical depression to launch themselves into such a project? I don’t know. But I have had letters (via email) from people thanking me, profusely, for helping them fight off depression simply through reading my book.

Is there a way . . .?