This may well be the last bulletin from Jupiter in 2023, so here’s hoping you aren’t hiding in the ruins of Gaza or freezing in the trenches of Ukraine, and I can wish you a warm and happy Christmas holiday – whatever your religion, even if, like me, you don’t have one.

At the end of last week’s piece I offered a ten-dollar deal on my Camera book, because I thought it would make a really nice present, but I’ve only had one taker, possibly because people don’t always read to the end. The deal runs through Monday, so if you want to buy the book for $40 use the code askingnicely when you checkout.

I wrote a little last week about my reception at the Triumph headquarters on the edge of Los Angeles, but there is more to say that I didn’t write about in the book.

During the ten days that they looked after me at the Griswold Inn they gave me another Triumph to ride while they took my bike apart.

The mechanic who was working on it didn’t care for conversation. He didn’t seem to understand that I had a personal relationship with it and that I was anxious to know how and why it had given me trouble.

In particular I wanted to know why I had run through two barrels and various pistons and rebores, but nobody there appeared to find that anything but normal. It was astonishing, in retrospect, that nobody paid any attention to the air filter, which was nothing more than a piece of paper in a perforated box.

Most of my troubles were caused by bad stuff getting into the combustion chamber. I only heard of K&N oil filters after my journey had ended, two years later, but apparently they had already been on the market for one or two years. Presumably they would have made a big difference, but nobody there seemed to either know or care. In fact, the prevailing belief in America seemed to be that Triumphs were only good for a few thousand miles of fun hauling ass before they fell apart.

Anyway, the people in the office were really just waiting for the place to crash around their ears. My mechanic told me he already had a job lined up at Yamaha.

What they did do was try to get a little publicity. And they told me, triumphantly, that they had secured an invitation to the Petersen Ranch on the edge of LA.

Looking it up now I see that there are two Petersen Ranches. One of them is a long-established spread belonging to deeply religious ranchers, devoted mainly to cattle – Holy Cows, I suppose. That is not where Triumph sent me.

The other Petersen was a publisher of mainly automotive magazines who had done well enough to buy his own ranch. Apparently, I was told, there were people there riding dirt bikes who would be enchanted to meet a man who had ridden half way round the world.

Brian Slark drew me a map to find the place. It was a very simple map with only three or four lines on it. It looked as though it was just around the corner. He didn’t explain that it was a hundred miles away.

It was a time when the highway engineers were experimenting with rain grooves on the freeways and they were not compatible with my tyres. Half the time it felt like riding on a skating rink and when I arrived at the ranch I was very ready for some warm appreciation.

What I found instead was a bunch of overweight, self-important middle-aged men on trail bikes, in suits that reminded me of the Michelin Man. Some of them had been World War Two bomber pilots. Clearly I had not been expected and they took no interest in me at all, until one of them peeled off from the group and asked me where I’d come from. I explained what I’d been doing for the past two years and he said, “Oh, yeah, I rode down to Guatemala one time.”

I had a beer and left.

Back at the factory I did make friends with a couple of mechanics who were working on a bike to break a speed record. One of them, Brent, was a particularly pleasant and thoughtful man and when my time at the Griswold was up and I had my own bike back he invited me to stay with him for a few days before heading North. I seem to remember that they lived in a garage in Paramount. It must have been a very big garage. Thanks to him and his very gorgeous wife, I learned that it was possible to live a pleasant, rewarding life in Los Angeles, after all.

From there, at the end of June, I rode north to San Francisco and, as you probably know, my life took a quite unexpected turn.

See you again in 2024. Happy wassailing!

If you remember, I came through the US border at Nogales with remarkable ease. It was late afternoon on a Saturday in May of 1975. I was tired after a day of riding through hot Mexican desert. My bike was limping along and would only run on full choke. I had no real sense of the distances I would have to cover in America and imagined myself to be practically there – in Los Angeles, that is. I stopped as soon as I could after about thirty miles. My notes became very sketchy, and need fleshing out to make sense.

To Rio Rica – campsite. Met young guys – one Viet vet – to girl friend’s house – soup, sandwich. Beer. Slept in hammock. Next day couldn’t get gas – man gave me some from truck. Talked about trying to get work – made it sound difficult.

Rode on through Tucson, Phoenix, into Mojave Desert.

Surprised at distance without gas – at desert itself – as hot as Mexico. Wind and sand. But the freeway made it seem less hostile. The Colorado River took me by surprise. Took a $3 berth at a KOA site by riverside. Much friendship and hospitality (beer generosity) – swam in river.

This was my first introduction to the snowdrop community – I was amazed by the RVs with their huge awnings, Astroturf and white picket fences. I can still remember how delicious was the ice-cold Coors. It never tasted so good again.

Next day more desert and high crosswinds made life quite difficult.

The bike would only run well at about 50 mph, so I was limited to the right lane, leaning over to compensate for the wind. The big trucks passing on my left cut off the wind abruptly, giving me some bad moments until I learned to deal with it.

Into LA – but it wasn’t.

I must have had an address for the Triumph offices in Duarte, but I had no idea that Duarte was a separate city. A young Englishman called Brian Slark received me with a handshake and a beer.

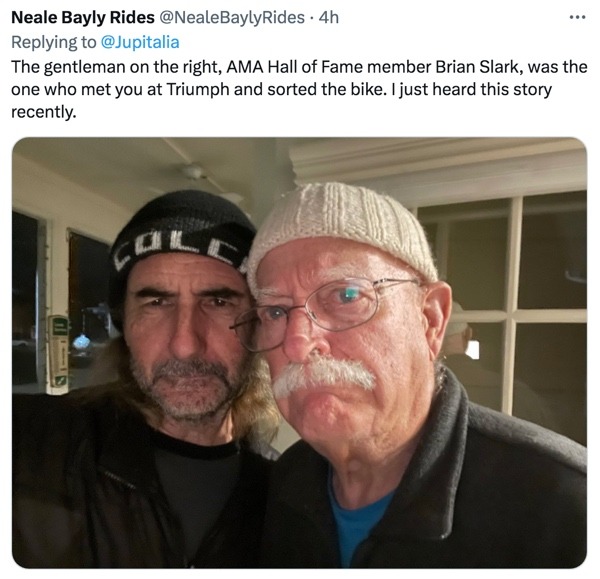

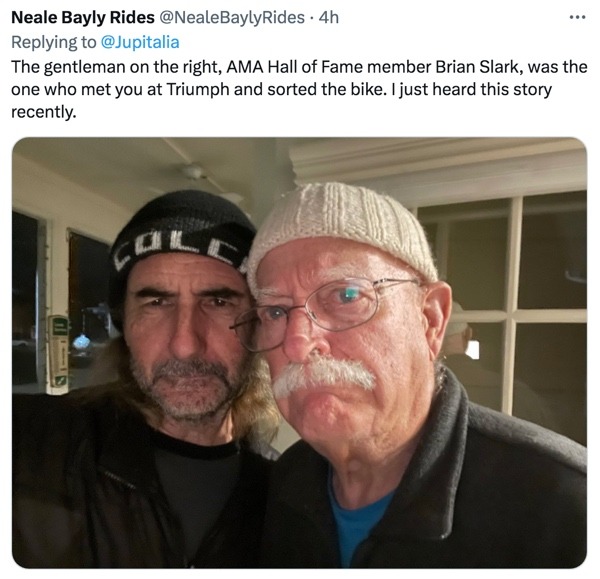

Just the other day Neale Bayly sent me a picture of Brian as he is today, from the Barber Museum in Alabama.

At this point I think it best to repeat what I wrote in Jupiter’s Travels:

I looked around Triumph’s prosperous offices with an optimistic eye, anticipating some sort of unspecified “good time.” Sure I wanted a beer, and a shower and a chance to change my clothes and even to rest for a bit, but what I really wanted was company, nice enthusiastic, appreciative company. As a Hero I naturally assumed that people would be tumbling over themselves to accompany me. All the keen athletic executives in the front office were extremely cordial. All the pretty girls at their stylish mahogany veneer desks smiled very nicely at me, but as the minutes passed my bright eyes glazed over. I wasn’t making contact. In spite of all the niceness, I knew they couldn’t really grasp who or what I was, and maybe, even, they were too preoccupied with other matters to care.

I must have been a strange sight. The desert sun had burned me very dark and printed a goggle pattern on my face. My shirt was threadbare, and my jeans were shredded across the knees and awkwardly patched. My hair was unfashionably short and disheveled, and I was a bit crazy at the thought of having actually arrived. I imagined myself to look quite romantic. After all, I was the real thing, but their nice, orderly eyes gradually convinced me that I was a bit of a mess, and the best thing I could do was go and clean up.

The credibility gap widened into a yawning chasm and never closed. They were unfailingly nice to me, and materially generous. They took the bike into their workshop and promised to give it all the care that could be lavished on it. They gave me another bike, the same model, to use in the meanwhile. They took me to a hotel about ten miles away and booked me in at their expense and left me there until the next day.

My hotel room was at ground level and had thick glass sliding doors instead of windows, with two sets of curtains. I had a square double bed with freshly laundered sheets every day. At the foot of the bed was a big color television set. There was a writing desk, itself quite a decent piece of furniture, and in the drawer was a stack of stationery and leaflets describing all the hotel’s services and telling romantic tales about its supposed history. I read them all avidly.

The bathroom had apparently been delivered by the manufacturer that morning. Everything in it was still wrapped or sealed by a paper band guaranteeing 100 per cent sterility. Not even the boys from homicide could have found a fingerprint in there.

They kept me there for ten days, a slave to luxury. That’s all for now. May I remind you that Jupiter’s Travels in Camera makes a really gorgeous Christmas present. If you ask me nicely I’ll knock $10 off the price for the holiday season (enter the discount code askingnicely when you checkout before 18th December.)

Two weeks ago I buried myself in the past to avoid the present, and today I can’t see any point in coming back. Almost anything I might have to say about current events would almost certainly provoke fury and outrage. So please join me again in 1975.

I had just crossed into the USA, limping along with a sick engine to Los Angeles where I hoped to get help.

Nothing had prepared me for the culture shock when I got there. After a week or two I wrote about it for The Sunday Times. They gave me a full page, and a bit more, and I can’t think of anything better to offer you now. It’s a long read, but I think it stands the test of time, so here it is:

What is it worth to make a Californian go “wheee!” or ‘wow!” or “Hey, look at that, will ya.” Millions? Billions? Whatever it is, Disney has spent it. Why, the Disneyland carpark alone is as big as Battersea fun fair, so big that it has its own transport system. Flowing gently under California’s great solar grill, the people come rolling over the tarmac on human baggage trains, hundreds at a time, starry-eyed again, about to take those rides again. Clickety, clickety, clickety, clickety… through the longest row of turnstiles you ever saw, £2 a head, just to get in.

First thing inside the gate is Main Street “where America grew up,” celebrating the Bicentennial Boom with gas lamps, trolley cars, barber poles, candy counters, girls in gingham and mutton-chopped waiters in baize aprons, clean as a whistle and neat as a nip (though not since Libya have I been in a land where never a drop of alcohol may be sold).

The main attraction for me is to watch the American families themselves – “Wilbur, don’t touch the gentleman” – parading in pastel pinks and greens and blues, in chiffon and jersey, bare backs and Bermuda shorts, Stetsons and sideburns, freckles and sneakers, and tons and tons of deodorant that keeps you “dry, drier, driest” for longer than ever before with absolutely NO ZIRCONIUM as advertised.

They spill out over the kingdom of fun and thrills in their tens of thousands but sooner or later they disappear, like bees among hives. Where are they going? How do they all fit in? The mystery is resolved underground, for Disneyland is an illusion floating on an illusion, and the heart of all this laboured hilarity is a subterranean labyrinth.

Here the technology of trivia comes to its climax. You float on a barge through a seemingly vast grotto where humanoid pirates enact scenes of battle, arson, pillage, rape, and various other rum doings, under a moonlit Caribbean sky. I stumble out to contemplate the immense resources that have been marshalled to distract me for a few moments.

It wrenches my mind, standing here, to recall that I am the same person who, a few months ago, was riding alone across the Bolivian Altiplano, more than two miles above sea level in a curtain of freezing drizzle. The day before, I had fallen in a river and lost the last of the plastic bags I used to protect my gloves from rain. My hands were frozen tight, and the cold was reaching up my arms.

My usual defence against cold is to sing, uproariously and defiantly, into the flying air – sea shanties and folk songs dimly remembered from the News Chronicle Song Book of 1937. For once the antidote failed. It became intolerable to continue, intolerable to stop. Rummaging in my mental attic for other remedies, I came across a story told to me about an Italian climber who survived a four-day blizzard on a vertiginous Alpine shelf while his companions perished. His method was rhythmically to clench and unclench his fingers – the only movement he could perform without falling.

I began to do the same on my handlebar grips. At first it was simply agonising. Then a biological miracle occurred in my arms. Warmth flooded down to meet the cold. It was such a precise reaction that I could tell where the interface was at any moment, felt it moving down past my wrist to the knuckles then the fingertips. Soon my whole body was tingling with life, and I travelled on to La Paz in an invisible bubble of warmth and comfort. There have been few other moments on the journey when I have known as great a sense of triumph.

On the bleak and frigid plain around me small herds of llama sat among the stony scrub, their long necks sticking up through the grey haze like periscopes in the North Sea. By the roadside, also squatting, were occasional Indian herdsmen wrapped in woollen mantles. The rain ran off their hats and trickled down over the sodden material. I pitied those grey pyramids of humanity and was as astonished by their stillness and acquiescence as they must have been by my frantic motion. I think now that they were probably quite as comfortable as I was. Perhaps we each wondered how the other could stand it.

It is customary to explain all feats of Indian endurance by their use of the Coca leaf but the information I gathered about that, in Potosí and other places, doesn’t support that view. Coca is an aid and a strong habit, but Indians (like all of us) have other more personal ways of generating defences against hunger and the elements.

Here in Los Angeles, I think about those Indians and, for the first time, it occurs to me to wonder how much they were worth in dollars. How much money, I mean, is represented by their possessions and the services provided to maintain them in their way of life? I don’t suppose it comes to a hundred dollars (fifty pounds) a head – maybe much less.

The question is unavoidable. Here, everything speaks to me of money. First the vast freeway constructions, a mesh of concrete carpet, four to eight lanes wide, laid out over thousands of square miles, with spiralling flyovers at every intersection. And the machinery that pounds over them day and night; it’s thirty miles there and thirty back to see a movie, visit a friend, eat a hamburger on the beach, do a job of work. Then the supermarkets and “Shopping Malls,” temples of a thousand options where you must look hard to find anything that a person really needs. Or the Marina del Rey, a nautical metropolis where unimaginable numbers of pleasure boats sprout from the quaysides like figs on a stick, most of them never having gone beyond the harbour wall.

What then would be the capital investment to maintain a citizen in his Los Angeles lifestyle? Divide the population into the value of rateable property, throw in the roads and freeways, the utilities and services which protect and succour him, and the figure cannot be less than 50,000 dollars a head. It may be twice that. Whichever the amount, it strikes me as utterly preposterous.

Is life a thousand times more rewarding, more healthy, more secure in LA than on the Altiplano? If I want access to education and medicine, to libraries and blood banks, must I defend myself first against smog, noise, crime and ugliness on every side? It’s easy to understand that the Indian has little choice, and even less practice at exercising it, but why in heaven’s name does anyone choose to stay in Los Angeles?

Los Angeles is certainly at one extreme of my American experience, just as the Altiplano is at another, and there is a perversity which attracts many kinds of person to extremes. I found that, while most North Americans living elsewhere profess to detest LA, those I met who lived in this city seemed quite content.

The inhabitant of LA has no generic label, like Londoner or New Yorker, to identify him. He calls himself a Southern Californian and is not properly speaking a city dweller at all because, in reality, there is no city, only an immense concrete waffle filled with property, most of it single-storey. He deals with in by creating an enclave for himself on one of those rectangular lots into which Los Angeles County is divided, and from there he exploits the stores, offices, studios and factories, paying very high rates for the privilege.

His car is an instrument of survival. Moving along the freeway, as though on a conveyor belt, it becomes a monkish cell in which he can contemplate, undistracted by the uniformly boring panorama outside and the dully predictable within. At other times, it enables him to get out of it altogether.

The art of life in LA, in short, is to block out as much of it as possible all the time and to escape quite frequently. As a solution for living it is fairly successful and very ingenious. It is also fearfully expensive.

Consumption is more than conspicuous, it gallops, despite recession or unemployment. Take paper products. In many homes paper plates seem virtually to have replaced china. In Californian “rest rooms,” by law, there must be a dispenser of large circles of sterile paper to interpose between your squeamish self and the lavatory seat (they have been dubbed “Nixon party hats”). There is a new product on the television, a douche, which is so disposable that it has apparently gone before you use it. “Just read the directions,” says the ad, “and throw it all away.”

If I had just flown in from Europe, it would have seemed merely extravagant (perhaps pleasantly so). But I come from nearly two years of living in open spaces, tent and hut, where human life is simple and the extravagance is left to nature. I find this custom of perpetual consumption physically and morally offensive. I can’t stomach it and it seems important to me to track that feeling to its source before it fades.

In the last fifteen months I have travelled 15,000 miles in Latin America from the north of Brazil to the south of Argentina, then from Chile up into the Andes of Bolivia and Peru, through Ecuador and Colombia, into Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala, and Mexico. Trying now with my mind’s eye to encompass this experience, three related impressions stand out.

First an intrusive presence everywhere of North American products, sales methods, and cultural appendages; second, the sense that, while Africa was a colonial empire, dismantled, Latin America is an economic empire still at its peak; and third that, compared with Africans, Latin Americans carry a heavy load of trouble and frustration.

Do not let me give the wrong impression. We live in a world of trouble. The essential thing is to distinguish between different kinds and degrees of trouble. I am not speaking here of revolutionary movements or clashes between nations, but of the quality of individual lives.

I also want to explain why the motorcycle turns out to be such a good instrument of exploration. It exceeds my greatest hopes. Its outstanding advantage is the very quality which once worried me most: it attracts attention.

Along all the endless thousands of miles of roadside in Africa and South America, excepting only the cauterised wastes of northern Kenya and the Argentine Pampa and Chaco, there is human life in all its manifestations. So much of my last two years has been spent riding past people that I have learned inevitably to read a great deal from people’s expressions. The Triumph and I are a rare if not unique event in most of these places, and the reactions to our passing are spontaneous and revealing.

Above all there are children and I know by heart, as though engraved there for 10,000 years, the attitude of the small boys, naked in the sun, half crouched, arms thrust out, fists clenched, grinning and howling half in fear, half in wonder, ready to fight, to run, to submit. Or the little girls, up on their toes, arms outstretched, palms open, arched towards me wanting instinctively to embrace this marvel before they turn to flee leaving a trail of enticing giggles behind them.

With age, dress and social conditioning, this basic vocabulary grows and ramifies to become the subtlest language of any but, because it is my language too, I have learned to read it. There is no time for dissimulation as I hurtle past. The messages I read are true, and they tell me whether these people are clear or confused, hostile or hospitable, oppressed or free, industrious or indolent, bright or dull.

Against the background of this almost continuous input of information there the casual meetings. At petrol stations for example.

Here’s one in South Africa:

“Ooooooh! Where you come from in that one, baas?”

He’s black, short, boiler-suited, working on the pumps. His face is a pantomime of wonder and appreciation. The servility is a game. It suits him to have me on a white man’s pedestal. He can enjoy me better up there. For us to meet on the same level in this white racist territory would be a long-drawn-out and painful process. I protest at the baas bit, but then we agree to humour each other.

“From England? Ooooooeeee! No! I couldn’t believe…Huh! All the way in this one?” And so on, and so on. He’s sly, but there’s no bitterness. I’d lay my life on it.

Here’s another, in Argentina:

“Where do you come from?”

The question is abrupt, even harsh, and uttered with a studied absence of interest. He’s 19 or 20, wearing salmon-pink bellbottoms, a plastic crocodile belt, a cotton shirt with the names and pictures of the world’s capitals printed on it, open to the waist and cut at the short sleeves to stretch nicely over his biceps.

He’s one of a group who are hanging about between the pump and the bar, punching each other occasionally on the arms. He wants to know only how fast the bike goes, and how much it cost. He suggests that I came most of the way from England on a ship. When I tell him otherwise, the explanation hardly appears to register. He’s so muscle-minded that he can’t see through his own image of himself. He’s proud, resentful, and curious, in that order. It’s too much work for me now to dig down to the curiosity. He saunters off disdainfully satisfied that at least I am no threat.

These two meetings, I find, represent very well the major social difference between Africa and Latin America. In Africa things appear much more straightforward. People seem to have their motivation fairly clear and simple and look reasonably at peace with themselves. There are glaring injustices. There is great cause for anger, confrontation and change, but in thinking how people are in themselves, I am left with a general sense of tranquillity and good humour (the one exception, Ethiopia, seems to prove the rule almost too nicely.)

Latin America leaves a different trace. The self-destructive aspects of the mestizo personality are eloquently described by many writers (e.g. Madariaga’s “Fall of the Spanish Empire”). A great part of any Latin American male’s behaviour is formed by a continual pursuit of his own identity, since he seems to exist for himself largely through the eyes of others. This makes him particularly susceptible to flattery: vulnerable to any challenge to his manhood, however puerile, and reluctant to seek information if doing so might reveal his ignorance.

He is, in short, a natural victim for anyone taking a colder, more collected view of his environment. A people for whom social respect opens the way to profit cannot hope to compete in business with a man who seeks profit first and then buys respect. The scene for the sacking of Latin America by the Anglo-Saxons was set centuries ago by the Conquistadors.

My journey to the United States began, I now realise, when I stepped off the ship in Brazil. I don’t know where else in the modern world one could pass over so great a landmass, among so many different nations and races all paying tribute to one distant power. At first, though, this didn’t occur to me. For one thing, I was locked up almost immediately by the Brazilian police which concentrated my mind for some weeks on a much closer and more frightening power. For another, motorcycling Gringos are a rarity in the north-east, and people did me the courtesy of asking where I came from without assuming that I was a North American.

I was 2000 miles further south in Rio before the prejudice became unavoidable. Then I was on foot, in a laundry, looking for some clothing that they had lost.

“Are you American?” the man asked, with his own peculiar brand of American accent, and an expression which showed that he was ready to jump either way. I said I was English.

“Good,” he said eagerly, jumping off the fence onto my side. “Americans are shit.”

If I had said I was American, he would probably have told me about some relation of his living in New York.

It didn’t occur to me to protest. I am no stranger to prejudice. The Libyans are contemptuous of the Egyptians. The Sudanese despise the Ethiopians. Africans have little good to say for Arabs, and none at all for Asians. Whites turn their noses up at blacks. A fine old Tunisian peasant entertained me handsomely in his mud hut and then, sipping coffee within two feet of me, told scandalous stories about Jews (I am half Jewish, whatever that may mean) and claimed to be able to smell all Jews from a great distance.

There is no shortage of prejudice between nations and races in South America either. It exists between Indians and mestizos, between Chilenos and Peruanos, Argentinos and Brasilleiros. Even in Brazil itself, supposedly a melting-pot of races, the rich white south is openly content to have few black skins to darken the view, and it is all too clear everywhere that the whites are on top of the pile and mean to stay there.

Yet none of this compares in generality and virulence with the prejudice against the United States, its power, its policies and its people. Whether expressed by thousands of people chanting slogans, or by hypocritical asides from the Spanish gentry; whether directed at dollar diplomacy, the US military, the CIA, or Yanquis and Gringos in general, it is heard everywhere as the one unifying idea in Latin America.

It is hard not to share the resentment. South American towns are often a parody of North American life. Shiny curtain-walled banks loom over hovels. In countless decrepit streets a brightly enamelled Coca cola or Pepsi cola sign juts out above every single doorway. Village shops are stocked less with what the peasantry needs than with what American technology produces. Everything has this lop-sided, disjointed feeling. The two cultures do not meet, they collide, and in spite of themselves Latin Americans know they haven’t the force to resist.

They never had time, or the inclination perhaps, to evolve their own independent systems. And yet, unlike the subjects of the British Empire in Africa, they were always nominally in charge of their own destinies. The gap between the myth and the reality was far too wide to bridge, and corruption was the only possible consequence. Nobody I have met in government or law really believes this process can be reversed. I am bound to say that I much prefer the consequences of British rule in Africa to what United States economic domination has done for the Americas.

The Latinos are quite imaginative enough to perceive the humiliating position they occupy vis a vis the “Gringos.” Their accumulation of rage and resentment is sad to observe, and sometimes personally unpleasant. On the West side of the continent, where the so-called Gringo Trail of tourists begins, I was spat on once from a lorry, had mud thrown at me twice, and heard the mocking cry of “Gringo” all the way from Bolivia to Panama and beyond. How I wished then I’d remembered to bring my Union Jack with me.

The British, in fact, are now perfectly placed in South America to enjoy maximum respect and affection. A once great nation reduced to “harmless uncle” status, we suit the psychological needs of Latin America very well. It’s half a century since the pound gave way to the dollar as the major source of foreign investment. There are nostalgic references to the railways we built, the polo tournaments we play, the shops and clubs we opened, and much flattery of London as the best city to live in.

I was fortunate to follow the Royal Yacht’s progress along the coast of Central America (at a respectful distance) and saw how well the old royal magic still works. By popular consensus, we are now all that the North Americans are not. We are civilised, sensitive to the feelings of others, clear of speech and clean of habit, and of course imbued for ever with the spirit of fair play. We are also comfortably old-fashioned.

The impression is helped along by the British communities which still remain. I had never thought to hear again the clarion voice of the ante-diluvian English girls prep school conclude a sentence with a ringing “What!” across the dinner table.

On the playing fields of the Bogota Sports Club I played my first full cricket match in 25 years. And in a smart hotel 10,000 feet above Lima, a tweedy English couple entered for dinner, each with a bull mastiff on a lead. Scanning the room, the gentleman loudly enquired of his spouse, “Same hole?”

For a traveller in search of space and beauty, South America is a heart-stopping experience. Everywhere I saw places where I felt I could cheerfully spend the rest of my days. Like the Atlantic beaches between Bahia and Rio, the luscious farmlands above the Parana River, or the lower slopes on either side of the southern Andes. I revelled in the spectacular fertility of the Colombian valleys and mountains, and countless other times felt myself in complete harmony with my surroundings.

Most of the time I had been moving alone through great vistas of plain and mountain, and it is to these memories that I am most drawn, rather than to the cities. For one who wants to live an economic, hard-working, balanced life in a natural environment, the world still seems to have room enough. I have at least a year of travelling left before the journey brings me back to England, but already I am impatient to stop, to put down roots and grow things. I am totally convinced now that this is the only healthy way to go.

For nearly two years I have been self-sufficient with what I carry on the motorcycle. I am delighted to discover how little a person needs, or even wants, as long as the mind and senses are kept open to the excitement that life itself has to offer. It is this knowledge, finally, that made the ride into Los Angeles such a bruising shock. I see the American consumer as an addict in the grip of a habit at least as, and vastly more expensive than, the Indian’s Coca leaf. It’s a habit which the planet cannot support for ever, certainly not for all its inhabitants.

But worse than that, it seems such a pity that all those resources, all that effort and ingenuity and promise of freedom, which people in Africa and Latin America envy so much, should lead to a sea of waste paper and a desperate attempt to get people to recycle their aluminium beer cans.