Articles published in March, 2025

The morning after a night of frenzied dancing outside the Barpeta Road police station.

A Girl in Gauhati, Assam

Friday January 14th

Morning, uneasiness persisted. It seemed even less likely that we would get our passports back so easily – although there was no real fear of anything unpleasant happening. Deb Roy came in and heard our account. We went to market, bought eggs, tomatoes. I ate two eggs. A crow ate the rest. We also got a tin of dried milk and had to sign our names in a register. Deb Roy said that after the Bangladesh war, refugees brought about a wave of shortages which lasted up to the Emergency, which was greatly exacerbated by sharks who bought up basic commodities and cornered them, making great profits. Many of them were later punished, and shopkeepers protect themselves by keeping a record of such purchases. Deb Roy continues to impress as a man with a good heart and a real curiosity for life. His bookcase too includes The Pentagon Papers.

So off to the police again. The Sober SI was there at his table on the verandah. He said he had not yet had instructions, though it was now 10.30. Shortly after, however, the phone ins his office rang. He sprang up, leaped off the verandah behind him, ran round the flower bed and up the verandah steps into the building and to his office. I saw him do this several times.

It was obviously much more pleasant to do business outside, and almost certainly he would have had difficulty getting an extension cord for the phone. But there were always minions floating about who could at least have picked up the receiver and called him. In the West he would have done it that way even if he was sitting next to the phone, for the status value.

But he preferred to propel his bulky body and arrive at the phone breathless. Why? Probably the only people who could call him would be superiors, so a hint of breathlessness would be a good thing. Servility is valued above efficiency. In 1957, Chaudhury Nirad C said, “People who are endowed with the power to provide employment in India are incapable of seeing any merit in a man without having it dinned into their ears.” Probably he would say the same twenty years later, and it goes without saying the sweeter the din the better, nothing being sweeter to the undiscerning than flattery and conspicuous awe.

Where the phone itself is concerned, in Assam it is still clearly an instrument of the Gods. I would not be surprised one day to see a calendar depicting Shiva on the telephone to – who? When, some days later I was in hot pursuit of a further set of permits, I was walked about in Gauhati preceded by a khaki clad messenger to no avail, when a simple call should have established that it was unnecessary. People like to send people on errands. It gives them a Caesarean glow to know that legions of messengers and supplicants are marching all about their empires on their business. They have not yet learned, as we have, that the territorial imperative can be asserted by telephone.

While the SSI was shouting “Yes Sir,” in his office, the DSI, now sober, sat behind and between us, still in his jacket and long red scarf. He had the slightly mournful look of a bloodhound which had lost the scent, but was otherwise of a quite sweet disposition. I had feared that on the morning after, memories of the night before might embarrass him and make him irascible but not so. I was glad for him that the uninhibition of the previous night could be so integral a part of his life that they required no explanation or compensation.

Above the SSI’s desk was a poster with thirty portraits of Wanted Men. Later, looking again I was startled to see that one of them closely resembled Nixon. And then I spotted Willy Brandt, et alia. They were the political leaders of the world in 1970. I remarked on it and the SSI laughed, but whether in recognition of the joke I couldn’t be sure.

The SSI returned. I can’t say he looked crestfallen. He simply said that his superior also felt incompetent to decide this issue, and that he advised that we be “produced” in Gauhati before the Special Branch for interrogation. His man would carry our passports, and we would accompany him on the train. The bike would stay at Barpeta Road.

I objected strongly to such a waste of our time and soon he agreed that if the DSI could get the use of the jeep he could convey us to Gauhati. So, resigned, we prepared for the journey, said “Fairwell” to Deb Roy, and then learned that the DSI’s jeep had been taken home by its driver, the passports had already gone by train, and we were free to make our own way.

Halfway there we stopped to photograph a stork, and were invited to a Bihu meal by a very gentle villager by the roadside, where two men were scooping water from one tank to another to catch fish – (water chestnuts). Food was rice cake with seed fillings. Rice & cardamon & sugar, in small enamel bowls. Very gentle ceremony.

In Gauhati just after dark, after crossing the immense and impressive Brahmaputra by the splendid double-decker road and rail bridge. To tourist lodge. Nice room.

Next day, phase two of the ordeal began. At the Special Branch office, I had to tell the story twice, each time in the face of resistance– to Dutta and then Das. Both seemed to have been won over, but it was holiday until Monday, so the “regularisation of Manas” had to wait till then.

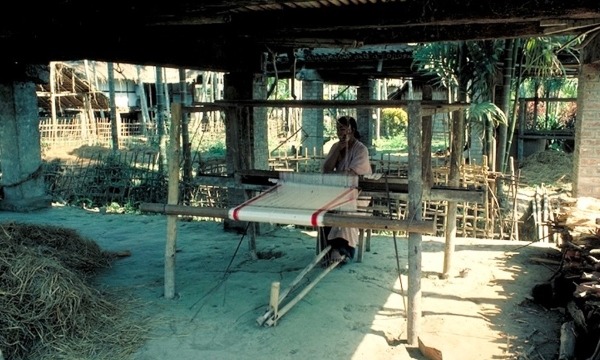

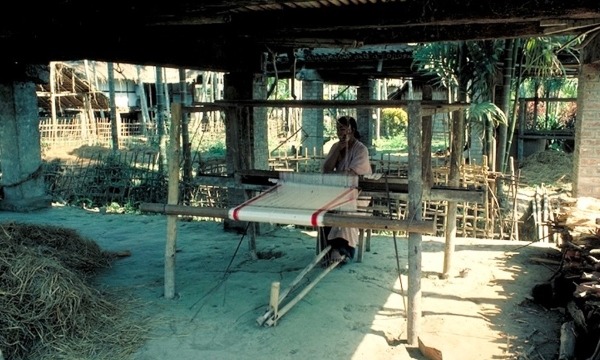

Meanwhile our application enabled us to visit Sualkuchi [Centre of textile/silk handlooms] the following day.

Silk weaving under the houses of Sualkuchi

[I listed the various deficiencies of the Indian bureaucracy. Normally I just took these things for granted and didn’t waste time complaining. Too easy to look like the pompous white man instructing the natives. I must have felt unusually frustrated.]

The 1st Secy at Nepal:” This permit is also valid for Manas.” Untrue

“You can go to Gauhati.” Untrue

Immigration officials: “You can go to Manas.” Untrue

Barpeta Road: No signs to indicate the correct road, or presence of a police post.

No understanding by police or SIB at Barpeta Road of correct procedure.

No machinery to assist tourists with correct information at Gauhati. In particular the officer at the Tourist Office in direct contradiction with the police on where permits are to be had.

Result: Six days at least spent in various police stations with no knowledge of what, if anything, can be achieved. And four days in which our passports were taken from us with no receipt.

Finally on Monday we get the retroactive permit and, planning to go to Dispur, we called at the Tourist Office. The officer was enthusiastic and insisted that we should not go to Dispur but to the Deputy Commissioner for Gauhati, Mr Misrah.

I found him that evening just as he was leaving his office, and he said come back next morning. He seemed competent to do it, a small man, quiet spoken, carefully controlled. At the Lodge itself police were also present – in the shape of a stocky man with white hair whom we came to know as “Snow White.” He asked us apparently aimless questions, cautioned us against visiting Sualkuchi, although Das had authorised it, and was anxious about our permits.

“Mr. Simon,” he said. “You seem much reduced.”

We also received Dutta in our room, who brought a copy of his poems and asked me to write some comment on them. His manner was always awkward, veering between expansive authority and stiff incomprehension – the contradiction between his roles being perfectly manifested in his behaviour, and his dress which was alternately dapper and down-at-heel. On a further visit he brought his wife, a lovely child-like lady in a beautifully embroidered shawl. He seemed embarrassed by her and apologised for her lack of English. He said she had insisted that a group photograph of us should be taken (but I wondered afterwards if it wasn’t his idea) and rushed out to find a photographer with a flash.

Thanks again, everyone, for letting me know you’re there.

I just came across an article I wrote for The Sunday Times after I had returned from my first long journey, in 1978. I think it makes for an interesting read today. They gave it a rather corny title, but I can’t think of a better one.

TRAVEL FAR AND LEARN ABOUT LIVING

The twin track of molten tyre rubber began halfway round the bend, a steeply descending right-hander on a Turkish mountain. I kept to the right side near the rock face, and watched the tracks veer away to the left and across the far edge of the road where they disappeared. Beyond the edge there were several hundred feet of nothing. Some policemen in rough khaki with red insignia stood nonchalantly looking down. I stopped the bike and joined them. Far below, the rear end of a lorry was visible. I rode on contemplating those fresh black tracks, imagining myself in the lorry driver’s seat as he was launched into space. It made me shudder.

I thought of the various ways it could have happened. One lorry overtaking another on the way up? Steering failure? Terminal fatigue? Some drivers on this Eastern run use opium to keep going. I went on to imagine how I would react if a lorry like that came hurtling round a corner towards me, and paid homage to the dead man by using his example to stay alive. It was one of the methods I employed to survive a 65,000-mile journey on a motorcycle.

On the road from India to England there were endless chances to learn from other men’s’ tragedies. At times one could imagine there was a war on. Seven thousand miles strewn with wrecks. A TIR juggernaut sliced in two, the cab here by the roadside, the container in a river 200 feet away. How could that happen? A new white Peugeot rammed down to chest height under the rear axle of a trailer. Tankers ripped open. Innumerable vehicles upside down. All the way through Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iran and Turkey the carnage mounts up as the traffic concentrates. On the Iran-Turkey border (a wonderful old-style frontier where you have to pass through a stone gateway) the biggest TIR trucks queue up, two abreast, in a two-mile-long line.

At the Pakistani end I was, in a sense, lucky. Newly proclaimed curfews and martial law had reduced the traffic to a trickle. I was privileged to see a great city, Lahore, apparently deserted by all life except for the cows moving majestically in herds along the broad thoroughfares, quite independent of man.

Worst of all was the notorious Yugoslav Autoput from Skopje to Zagreb. Juggernauts and impatient German tourists bound for Greece pack these 800 miles of two lane monotony as tightly as the meat in a sausage skin. The skin of course bursts in frequent and bloody accidents.

Nowhere on the 7000 miles from Delhi to London is it a difficult ride, unless one chooses to cross the high passes in winter. (In Africa and along the South American Cordillera I had a much tougher time with rocks, sand, mud, flood, and corrugation). After four years of traveling I was glad to have this relatively easy – and often tarred – surface rolled out for me all the way home but, thank heaven, I had also acquired the road sense to survive on it.

Many people who took an interest in my journey consider that my greatest accomplishment was to come back alive. With my mind full of more positive benefits this seems like the least important achievement, though it was done with great effort. But at least it proves that the odds, however bad they may seem statistically, can be defeated. The only serious injury I suffered –to an eye – was due to a fishing accident.

I found the best aid to survival was the old truckie’s motto, “drive the next mile.” to which I would add my own corollary for motorcyclists “and don’t let the other fellow get you.” Most people believe that situations can arise on the road which make them helpless victims of chance. I think you stand a much better chance if you believe that everything that happens to you on the road is your own fault. Everything.

The truly astonishing volume of traffic that now surges up and down the Great Orient Expressway has rather overshadowed what used to be called the Hippy Trail. but the Hippies still flourish. The “freak buses” still plough between Munich and Goa, Amsterdam and Khatmandu, advertising stereo sound, free tea and fully collapsible seats. In little rooms in Kandahar, Europeans wearing odd combinations of ethnic dress, from Turkish Depression gear to Gujarati mirror clothes, still fondle polished slabs of compressed hashish and dream about the price on the streets of Paris and Hamburg. And dope-hunting Iranian police still make tourists turn their camper vans inside out at the Afghan border where cornflake packets and supplies of Tampax blow away in the high wind. So it is all the more bizarre to find oneself riding in central Turkey among bountiful acres of white and purple opium poppies, their fat pods ripening for another harvest of morphine base.

The anti-Hippy crusades pursued with gusto by some Asian authorities may have been justified but seem designed mainly to clear the way for the big spenders of tourism.

What is a Hippy?

“If you are found dressed in shabby, dirty, or indecent clothing, or living in temporary or makeshift shelters you will be deemed to be a Hippy. Your visit pass will be cancelled and you will be ordered to leave Malaysia within 24 hours . . . . Furthermore you will not be permitted to enter Malaysia again.”

Signed: Mohd. Khalil bin Hj. Hussein

Dir Gen of Immigration

The above definition would have included me with my tent and jeans as well as a high proportion of the native population.

In Nepal “every guest who is in Immigration for their problames (sic) should be polite and noble behaved, any misbehaved activities and discussion by the guest shall be proved a crime”.

Difficult advice to follow in view of the impolite and ignoble behaviour of the officials there.

However Mother India remains mercifully benign to all comers. A few more people in shabby clothes and makeshift shelters are not going to make much of a dent on several hundred millions in the same state. As long as India is India the Trail will live on.

These have been four crucial and violent years to travel in the world. Of the 45 countries I visited, 18 have been through war or revolution. Many of the rest have faced economic depression or internal violence. Yet my own experience has been overwhelmingly peaceful, marked by kindness and hospitality everywhere.

I have returned to find prices double, the European pecking order changed, and the political complexion of Europe much pinker than it was. Britain seems a bit chastened but otherwise unchanged. People are as oblivious as ever of their relatively great material wealth. I suppose they are right to be, since what we have here is not really important to the quality of life; indeed most of it, to my mind, is a burden. My mother’s garden, about half an acre of lawn, flowers and fruit trees, could accommodate an Indian slum of a thousand inhabitants (not that I suggest it should). I watch her move about in it alone, pruning and trimming, and I imagine she wishes there were less to do.

I used the word slum, but for me that denotes people who have abandoned hope in their squalor. The Indian slums that I saw were not like that. They were scrupulously maintained in the village tradition. Given just a few amenities (a source of clean water within reach, drainage, a supply of roof tiles, they would reach an acceptable minimum standard. Direct comparisons between European and Indian lifestyles are as fraudulent as ever.

I have spent a lot of time wondering how “they” could arrive at some sort of parity with “us”. During these four years “they” have acquired much more power to press their demands. I see no alternative: we shall have to sacrifice some of our abnormal privileges. If we did it gracefully and imaginatively we could benefit a great deal from the sacrifice, but I expect it will be a bitter and bloody business in the end. Around the world I have been asked to defend Britain in her “decline” and have tried to conjure up some notion of a British “genius” at work. Under the stresses of these last years I thought maybe new directions would be found, new social forms experimented with. I see now that this was foolish. We still carry so much fat. There is no sense of change, just an occasional whiff of decay.

But things will change. Having been among the two billions who will demand it I know they are not just images on a screen or on posters for Oxfam. They are real. We will have to accommodate them.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

“How will you ever be able to settle down?” people ask. “Will you want to do it again?” I used to laugh. The prospect of stopping in one place, of doing some real work and living among familiar faces was all I could dream of. The book I have to write has been on my mind too long, but now I realise that until the book is written the journey will still not be over. And already I know what makes the tramp go back on the road. There’s a tingling vista of freedom that is as elusive as it is intoxicating, and it is peculiar I think to those who travel widely alone. There is a wild pleasure in being able to vary one’s behaviour at will, with nobody around to remind you of what you said or did yesterday.

For example, I used to take it for granted that I preferred to sleep on a bed. In these four years I have slept on all kinds of surfaces, wet or dry, hot or cold, in a prison and in a Maharaja’s palace, still or moving, in pin-drop silence or in railway platform bedlam. I now find that I would choose, whenever possible, to sleep on a rug on the ground in the open air.

Why does it matter? To me, enormously. The habits of sleeping, eating, drinking, washing, dressing that I learned in youth had great influence on my state of mind and body. But they are not habits I would have chosen and in these four years they have all changed. In many ways I find that the old ways of doing things were unnecessarily complicated and expensive. Today what I do is much closer to what I am.

It does not take much imagination to see that the same process applies to less tangible but even more potent habits of behaviour. I think I used to make great efforts when meeting people for the first time to impress them. This kind of thing obviously demands a lot of energy and creates a good deal of anxiety as well. If I had tried to sustain it through four years during which I met, practically every day, new people from whom I wanted help, often with no common language to fall back on, it would have made me a quivering wreck. Relax or crack were the only possible alternatives. I managed to relax by abandoning expectations.

“Whatever it is you want” I told myself, “you don’t need.” Whether it was a visa or a pound of rice, or permission to sleep on somebody’s land, I prepared myself in advance to be content with refusal. The result was a revolutionary illumination. I was almost always given what I wanted and at the same time I found I wanted much less.

These personal discoveries once begun, became the foundation for a philosophy which, while in no way startling, is intensely real to me, having arisen out of my own personal experiments.

Towards the end of the journey the power I had built up in this way began to fail. There is obviously a limit to a learning process like this; in my case about three years. After many months in India I began to wish I was home. I knew the wish was dangerous and debilitating. To hurry now would invite the accident I had avoided for almost 60,000 miles.

In Delhi I became absurdly frustrated by a delay of two weeks in getting some spare parts. When I finally climbed out of Old India through the Khyber Pass into Afghanistan, I experienced a psychological dizziness that astonished me and kept me in Kabul days longer than I intended. It had a lot to do with the way I had adapted to the pressure of Indian life, the permanent exposure to people, their curiosity, hunger and clamour. Coming out of that was perhaps like decompression for a diver, but earlier in the journey I would have taken the transition in my stride.

On the long route home, I made mistakes attributable only to apathy. For the first time I looked for companions to ride with and used them to support my faltering spirits. And finally, in Istanbul, I lost all restraint, and I rode for home almost non-stop, getting to Munich in three days although I dared not take the bike over 50mph.

Somewhere along the way I wrenched my back and so, having spent four years in almost perfect health I managed to arrive home a physical wreck. And my imagination having worked overtime for so long went into a coma. For many days I could hardly recall, with any conviction anything that had happened to me “out there.”

For a while I felt as though those four years had never happened at all.

Bengal Tiger at a reserve in India. Photo by Soumyajit Nandy.

Thursday January 13th

After morning ride with Debroy, back to tent, a meagre breakfast (one egg and a chapati between us) and packing. To see the Beat Officer, a curiously evanescent character whose ornate English phrases are unequal to the thoughts he tries to capture.

“I will be performing my utmost to render your visit…” and so on. But his answer to all questions an enthusiastic but uncomprehending, “Yes.”

We talk a little. He says his superior has decided to waive the camping charge, and we get off with 30 rupees each for three days. He presses me to take the boat ride, but I demur. I ask him about himself. He is 27.

“You cannot say I have many years. Still there is the main part to come.” And, “loneliness is my companion.” He repeats this several times. Wistful, and more endearing than before.

So we ride away, much faster and surer than before over the loose surface. Carol has the beginnings of a toothache. We are both hungry and looking forward to a meal. Then the plot suddenly takes a strange twist. At the point where, on the way in, we did our mistaken loop off the main road, we keep on the road and are unexpectedly stopped by a painted barrier held down by a padlocked cable.

A man asks us to show passports. I’m so surprised, I react a bit uppish, but we follow him in as it dawns on me that this is a police post of some sort which we inadvertently avoided on our way in. The two men who take our passports go through a very similar routine as the two at the frontier of Assam, but this time roles reversed.

The writer is an unusually sophisticated young man with a cultivated understanding of our feelings. The other is a ponderous, bull-headed man. He and I start with a foolish argument about how we came to take the wrong road coming in. He says there’s a sign. I protest that there is none. The suave one cuts in saying very pleasantly, “Please sit down. Did you enjoy Manas?” Then they read through the passports and Carol has to tell them that she’s a history teacher. We too smile and joke about the misunderstandings.

“You do not have a permit for Manas.”

“This is the permit here, given in Katmandu.”

“But it does not mention Manas.”

“But we were told it was valid for Manas.”

“You should have a special permit.”

“How were we to know. We have told everyone we were coming here. No-one mentioned that a special permit was need, etc., etc.”

After consultations and phone calls they say our passports must be sent to Tezpur.

“How far away is that?”

400 kilometres.

“And what do we do meanwhile? Stay here?”

The writer smiles apologetically.

In a heated fashion I ask whether the First Secretary in Katmandu will be put to the same inconvenience for misleading us. After another pause, he says our passports will be sent instead to Barpeta Road to save us inconvenience. A man will take them on a bus and we should report there to the police station.

We leave, and I lose an opportunity to convey to the civilized one that I respect him.

At Barpeta we go to the Sikh truck stop to eat paratha, rice and curry. Then to the IB [Inspection Bungalow]. Where we meet Debroy and tell him our story. He ponders the matter, but it seems he can do nothing to affect the issue. The IB is very pleasant and homely – nice beds, clean carpet, a dining room, new mosquito nets, and bright lighting – a real pleasure.

So we leave for the Police station. The duty policeman already has our passports. He seats us and asks what it’s all about. My explanation runs through three quarters of its length before he interrupts. (I am never able, really, to explain the whole thing to anyone. It’s as though they are listening for another kind of meaning behind my words}.

He is increasingly polite and friendly – a good-looking, athletic – warlike – man. He was in Kashmir for the Pakistani war. He apologises that his superior is at the market and will return in half an hour. Then we will get our passports back. While waiting, observe the office. A door behind us opens onto the Super’s office. On my left two barred metal doors labelled Male and Female lockup. On the facing wall another such door labelled Malkhana – which means House of Evidence where case exhibits (like our passports) are kept. The floor is eroded cement. A dusty box has a collection of empty bottles standing on it. Some standing shelves between the lockups have old files, all very dusty.

We ask leave to go and return in half an hour. At the IB is a medical officer travelling around heath centres to eradicate smallpox. He has studied the map on the bike, explains that he has understood exactly where I come from and what I have done.

“This is the Union Jack,” he says jovially. “We were saluting this flag for a long time.” Then he tells me immediately who he is and what he does.

“We have succeeded in almost eradicating it.”

We go back to the station. Now we are received by the Superintendent. (Actually, a sub-Inspector) a precisely efficient (if humourless) man in khaki.

“What is your problem?” he asks. How can he fail to know? He claims to be principally concerned that our passports were taken and no receipt given.

“This should be penalised,” he says. “I shall take action. Meanwhile if there is anything I can do . . .” and he offered immense but unspecified services. Then the extraordinary man in the orange scarf and the jacket from Chicago, already quite drunk, came in and added to the profusion of wishes, compliments, promises of immediate restitution, justice and unlimited aid. Then he started singing ‘Clementine’ followed by ‘Yippy-yippy-yay’ and an unknown song about Seven Lonely Days and Seven Lonely Nights. As he sang the superintendent held his hands before his face in mute embarrassment. But then I began to sing with the drunk and perhaps that helped. Anyway we were brought tea and rasgulis (delicious) and told that next morning, as soon as the Supt. had his instructions, we would receive our passports. Meanwhile we were to be the guests of the drunk, and we followed him to his cramped quarters where the duty policeman and some others were already helping themselves to brandy and water.

The drunk sang and talked and quoted proverbs. “If this drink is intoxicating, why is not this bottle dancing?” and so on. And the others also warmed up. One was a nice but sober Brahmin landlord – owns a lot of the land of Barpeta. The other was, astonishingly, introduced as India’s foremost actor of stage and screen, a Mr, D……… Pal who smiled shyly. And so we all trooped out to the lawn in front of the polices station where some constables had lit a wood fire.

Then came another dramatic transformation. This ragged band of PCs, some with bare feet, some with cloths round their heads, some in civilian clothes, became an eloquent tribal group of dancers and drummers. The drunken sub-inspector had kept up a continuous level of song and nonsense, but so far there was no sign that anyone else’s spirits were raised at all.

Occasionally to the tune of Clementine he danced a strange little jig, with one leg bent and the other sandalled foot raised and jabbing at the air under his tubby body which also twisted about. Sometimes he took the ends of his endless scarf and held them out from his body like some ceremonial dress, in a rather feminine gesture, while sweet expressions suffused his face. Though of course from one point of view he was just a drunk making a fool of himself, in this context he was a catalyst for all of us to lose our senses.

He had promised songs and dances. The drummer came across from the other side of the fire, a lean man with a fine grin, hooded by a scarf. His drum was of the truncated egg variety with string longitudinally stretched on the body. He tapped the rhythm on the side with a stick – double hand clap to four-time, then finished each sequence with a great flourish of beats in quite subtle combinations. “This is the bull” says the Inspector.

The first dance took us quite by surprise. The DSI (Drunken sub-inspector) was declaiming something to the houses but this time his remarks are greeted by a chorus of responses and animal growls. Then the Duty Constable (DC) raised his arms and went into a sinuous dance while the others with one sustained howling first note broke into a song of simple, powerful forms supported by drum and hands. The group in the firelight became as solid and intense as the Turkana were at Lodwar, and it was all the more extraordinary because these were policemen in uniform and the trappings of their trade were all around, while we, sitting there as honoured guests, had our passports locked up in their Malkhana.

The dancing continued with even greater effect. The DC’s hands moved with great eloquence over his forehead and behind his back. Another young man joined in and danced a completely different movement that may have been from another area. The DSI continued his jig, weaving among them and occasionally confirming that they were all in heavenly ecstasy due to our presence. The DC also kept telling us not to mind.

“Don’t mind.” We danced ourselves. Carol wore the DSI’s shawl, made by his mother, and then the scarf too. I wore his funny leather peaked hat. He called us brother and sister.

While my enjoyment and appreciation were undiluted, I still recognised a small voice murmuring “tomorrow maybe they’ll throw you in the lock-up.” Not pure paranoia, though I recognised the South American influence. But the emotional ties that bound us to them tonight were fireworks, and would be dead sticks in the morning. Meanwhile we were there under their supervision and they had our passports.

[By this time I had discovered that we happened to have arrived on a day of state-wide celebration called Bihu.]

Eventually the dinner was ready. The Supt. and the Brahmin came over saying “Yes please,” in that strangely abrupt way they have which leaves you wondering whether you’ve been invited or ordered to come. In the circumstances one wondered whether the sober ones were quite as friendly towards us as the drunks. But the landlord was very friendly to Carol at the feast, and the Supt. continued offering his services vociferously into the night. Although his persistent idea of giving us a constable to guard over us had a sinister side.

We did our best with the food, served on segments of banana trunk. It was delicious but far too much. Then we were whisked off with extraordinary speed and violence. The DC who was now smelling heavily of liquor seemed determined to walk us (or march us) back to the IB and was pushing and prodding us toward the exit. Then the Supt. took over and we were bundled into the jeep instead. There was scarcely time to say goodbye to anyone, enhancing the feeling that we were mere cyphers, or symbols, or ghosts at the feast.

Contemplating it all afterwards I felt as uncertain about the next day as if the celebration had never taken place. One other thing occurred to me. The Superintendent’s emphasis on the business of receipts for passports echoed loudly Debroy’s own remarks when we first told him of our troubles. Had Debroy quietly called a friend and suggested this line of defence against the SIB. Perhaps we’ll never know.

[The SIB, or simply IB, was India’s Intelligence branch, supposedly capable of making life very unpleasant, or worse.]

The moment I sit down to write this memoir, a knock on the door. Our hero, the DC, had come out on foot. Why? “Are you all right?” he demanded, as though he had just relieved us from a siege. He seemed to swell up and fill the door frame, beaming down on us with drunken eyes and breath. “Anything you want, you may call for me,” and then astonishingly he advanced on me, seized both my biceps in his hands and kissed me firmly on each cheek. And in the same mood of heroic resolution, he did the same for Carol, though there was a brief moment when his mouth seemed to be aimed at hers and only a mighty effort deflected it at the last moment. Then he stumbled off into the fog, nursing his Punjabi passions.

Still in Nepal, we’re moving across the lower reaches of the Himalaya to the Indian border. First, I wanted to visit Darjeeling, famous as an outpost of Empire and for the tea that bears its name. After that we intended to enter the state of Assam, and visit two tiger sanctuaries, Manas and Kazirenga. Assam was politically sensitive, and tightly controlled. It has a tribal population, and borders with China, but I believed we had been given the necessary permits from the Indian consulate in Kathmandu.

January 6th. Dahran to Siliguri

Indian road continues. People are unusually indifferent to traffic. To border with 4 rupees (Nepali) left. Tea and puri. Border crossing easy, tho’ much to-ing and fro-ing with carnet. On the Indian side a single individual in a tent observes a calm ritual, with good humour. Marked contrast, but carnet has to be done in next town. Both given cups of tea. I walk away and am called back. “Have you any small arms? Have you nothing to declare?” Then smiles, and we’re on our way.

January 7th. To Darjeeling

Oberoi hotel built 1914-16, by Armenian. Bought by Oberoi [a hotel chain] in 1957. Grey stone fortress. Cosy English bedroom. Coal fire. Cast iron grate and moulding straight from Edwardian England. Hot bath. Old-fashioned bed. Very comforting. Even fog begins to acquire some charm, and even if the water doesn’t run hot in our bathroom there are hundreds of other bathrooms to choose from. Otherwise, the Youth Hostel and the old English Tea house called Glenary’s. Then Campbell Cottage and Primrose Villas. Painted roof with fretted wood, and wood frames painted liberally with white paint, like a war-widow’s lipstick. Toy train’s whistle through the fog. Tibetan boys touting horse rides. (Three rupees an hour).

Oberoi manager (Mr. Mattol) very pleasant. Took picture and promised to send print with caption for his travel magazine. Hotel virtually empty. (I’m sure the six other guests were enjoying special favours.) The town seems to be all road, with vertical drops between on which houses, hotels, shops teeter precariously. Remember the Buddhist home for children, listen to voices chanting from inside. A sound that evoked a complete life. like Trench Hall perhaps, so foreign yet so familiar.

The problem of how far we travel together has many faces. As I confront any one of them I feel the others staring at me from behind. The Saluga hotel in Siliguri is scene of a decision. The bike is too heavy with everything on it. I suggest that Carol find something to do with her stuff, or take train to Gauhati. [Capital of Assam.] C. says, most equably, that it’s entirely up to me (and for the first time I can believe her). But if I leave my own gear at Siliguri that might save enough space to leave one bag behind. Reluctantly I try it and find she’s right. She leaves a few things for me to take as far as Delhi [We planned to meet again briefly in Delhi.] and the leather bag and a few bits go into the storeroom. For once the whole thing is managed without a crisis and I’m very grateful.

When confronted with the choice of saving weight or saving a relationship, how can any decision have value. Of course, I could theoretically surrender control of everything and see whether it is returned to me as a gift. But I could not be so free with my life (and it seems to me that nothing less is at stake.) Between Katmandu and Siliguri we had two difficult moments. One was outright anger by Carol at my “supervision” of the packing.

“You must think I’m totally stupid. I don’t know why you would want to be with such a total moron.” I came back in the same vein.

Sunday January 9th, East from Siliguri

21,018 miles. Tightened chain. Noticed that oiler had dried up and opened it an eighth of a turn. Reset tappets. Rt exh. very loose. Pt setting right, but pts should be levelled and polished. Cleaned air filter. Oil is now down to “full” marker, i.e.used a lot in last 100 miles as against almost none from Katmandhu. [Oil consumption had become a mystery.] This oil was changed at 21,050. [Obviously a mistaken reading.] Plugs now a good colour. Petrol consumption seems to have been high but will see how much tank now takes. Since Hetauda 398 miles. 20 litres plus 10.

Manas

[Tiger population in Manas down from 2000 in 1964 to 2 or 3 hundred now. 3000 in Kazirenga. Meanwhile I had gathered more information about Manas, where we were now headed.]

Assam trees – Sahl, hardwood. Teak will grow, and plantations are starting.

Tigers move in triangles – in one spot for a week or so, then 15 miles to the next spot, and so on, to return to original site.

SW monsoon comes up from the Bay of Bengal to hit the Khasi hills, where it divides into two streams. Half follows the Brahmaputra. Other half stays south. Each carries hundred inches of rainfall. They meet and the rainfall doubles, but on top of hills it is dry in places.

In Orissa, see Chauderi (SB) Field Director, Simlipur, rearing a tigress.

S.Debroy, Field Director, Manas Tiger Project

Mr Das, Conservator (Forestry) – previously Finance.

[The road to Manas left the main highway at a village called Barpeta Road. I followed it to a fork where I could see no signs, and took the left fork which passed through another village and came out to rejoin what I realised must have been the other fork. We continued to Manas where we were well received by Das and Debroy.]

Village houses in Assam.

Debroy is of medium height, medium colour, good physical shape. Square head and face, straight mouth, level brows and close-trimmed mustache just above the lip. At first last night he seemed a bit sullen, reluctant to talk, but this may have been resentment at being towed along in the wake of the other dignitaries. At any rate, when I began to ask about tigers, mentioning that Das had told me they move in triangles he became more animated. Made it clear without saying so, that Das didn’t know what he was talking about, and began to pour out tiger lore. Latest census shows 54 tigers at Manas. They are a solitary animal, being together only for mating (there is no strict season) and for the first 18 months of the cub’s life. They are very shy, always move in heavy cover, are not nocturnal like leopards but hunt very early or late in the day, eating as much of their kill as they can, and hiding the remains from vultures and other smaller cats. Then they find water before lying up nearby to sleep. If there’s plenty of game they don’t move far. When the game is gone, they move on. From the pug marks you can tell sex and age of tiger.

Debroy said he had noticed that the deer had disappeared from a place near the road and went out in the jeep that morning to see whether a tiger had been moving through. Sure enough, he found the print on the road where he would have expected it if the tiger had made a kill and then gone for water.

I began to get interested in what could be read or imagined into game tracks. Debroy has been round the main reserves of East Africa. He says he got “fed up” with seeing so much game. Now I begin to understand his tastes, when it becomes a matter of constructing the presence and behaviour of an animal you can rarely if ever see, when all your information is based on the disturbances on the environment, like studying magnetism, or God. (NB it might be interesting to postulate a novel in which for some reason a person must be investigated without ever being seen [Harry Lime?]

I asked if I could accompany him on such a trip in the sanctuary. He thought about it and said he might be doing it again the following morning but, gesturing with his thumb at the upstairs room where Das could be heard enthusiastically lecturing Carol, you never knew what might happen. But if he went, I could come.

I asked what the light was, suffusing an area on the horizon. It was whitish like the lights of a distant town. He said it was probably controlled burning of grass. (Thatching grass). They did this to prevent the grass from catching fire accidentally in later months. There was some controversy over whether it was ecologically sounder to burn or not. In the first case you destroyed many micro habitats, perhaps driving some small species out altogether, in the second case you risked wholesale destruction. Debroy thought that since burning off land had been practiced in India for thousands of years the ecology was probably in balance with it by now. But the balance was delicate, particularly where tigers are concerned. Their numbers were so reduced now, that theirs was first priority.

Mrs Ghandi wanted all tourism banned in Manas until the numbers had grown. They were now investigating and reporting to establish whether this could be a useful step. Das earlier talked about the same thing but seemed to think that Mrs.G should not get her way. “We are a democratic country,” he said. “We can’t stop people from coming here.” A non-sequitur, but the feeling of resistance to imposition from Delhi was there. My own prejudice, however, suggested that Mr. Das was more concerned to project his own authority than the rights of the people.

Next morning Debroy sent a man to the tent to wake us. It was just after dawn. Grey light. He came soon afterwards with a jeep. He had a woolen hat over sleekly groomed hair and a green army jacket. The shoelaces of his half boots were undone. A man crouched in the back. We set off down the road we’d come in by. He showed the tiger print he’d seen yesterday. There were no fresher prints. He thought he must have been wrong about the kill. If she’s made a kill she would have come back for it. We saw deer tracks, elephant (wild because they won’t cross culverts or bridges) wild buffalo, with the widely separated segments of hoof spanning 7 or 8 inches, and the wild ox, or Gauer, with closed hoof. Wild buffalo grow to nine feet at the shoulder, the sturdiest animal in the jungle, and very strong. From the dirt road we went onto a grassy road and into a marshy area of shrubs covered with creepers and all ground choked with vegetation. Here a lot of elephant grass grew and at last I found out what it was. A stalk 3 to 4 feet high with substantial leaves growing from it. Man can eat the tender portions too. More tiger tracks on the road when we turned back.

This experience with Debroy transformed for us, the nature of the Jangel [The Indian word for Jungle. Strictly speaking for a forest to be called Jungle there should be tigers] and it became possible to visualise the life that went on inside it.

More exciting adventures to come. Watch this space!

I feel the need to emphasise that these notes, taken directly from my notebooks, were intended simply to remind me of thoughts, events, impressions which I might otherwise have forgotten. They were never intended to be seen by anyone, and much of what I wrote would make little sense to a third party. Nor was I particularly concerned with my choice of words. This is simply the raw material from which Jupiter’s Travels and Riding High were later constructed. I have done my best, in italics, to explain and fill in where it seems necessary.

My four-year journey was essentially a solitary one, and this was extremely important to me, but had I made an exception for Carol, and agreed to take her with me through Nepal and Assam. The prospect of my having to leave her created a sad undertone, because I knew she could not really be expected to understand my motivation. In this installment Carol and I are on day three of our trek up the Annapurna trail. I have never been happy carrying a rucksack. My shoulders are just not adapted.

December 15th 1976

To Ghorepani (9,300ft) from Tirkedanga (4,900ft)

We’re on the north side (right bank going upstream) of the Burunghok Kola. The river runs into the valley up which we travel at a point about halfway to Ghorepani and then joins the Madi Kola at Ghorepani. Soon after T. the trail descends and crosses the Burunghok Khola to climb up to Vilari – a steep climb. We breakfasted there. Woman with filthy hands. Then rest of the 4,400 ft climb to G. We arrived just after sunset when the cold really begins to bite. Were delighted to find that hotel has huge fire in the centre of the room. The chimney, a sculpture of flattened cans was purely ornamental, and smoke was a problem, but the evening was undeniably cosy. A lot of people were gathered there. And double bed at night kept us very warm. Sunrise on Poon Hill, after a struggle.

Bina’s famous Bar & Grill. (A joke, of course. Lentils, rice and cabbage is what you get.)

Hot Water. 4000 ft. First up another 200 then down 5,500. But this side of the ridge is more open and gentle, with terraces everywhere on all faces of the valley and even on a most inhospitable rocky face in distance. Many houses, villages. Tea at Bina’s Bar and Grill where I posted my letter to Pat. The stamp was cancelled by hand. [Pat Kavanagh was my agent in London. She had written to tell me that The Sunday Times were complaining that I was costing them too much. I was angry and depressed because I had struggled to survive on a shoe-string, and most of the money they had spent was on entirely avoidable things, like communications and bank stuff.]

While walking, my preoccupations are: 1 Discomfort and strain. Thoughts about enduring it, overcoming it, wishing I hadn’t started. Wondering if I’ll get used to it. Experiments with breathing. Trouble with right knee which I trace to childhood accident and, later, Macchu Pichu. 2 Attempts to divine atmosphere of Europe in Middle Ages. 3 Thoughts about my present bad relations with the Sunday Times. 4 Saint Privat, my commitments to Carol, how to reconcile two future lifestyles.

Hand-weaving silk by the roadside.

Arrive Tato Pani. Talk to quiet tourist outside first hotel, run by Japanese married to Nepali woman. He says they were at the Dalaigiri Hotel but pulled out when they found a hepatitis case was staying there. We go to Namaste Lodge and get a double bed at back. Two Australian girls.

[From this point I made no further entries until we were back in Khatmandu and ready to leave again. We had intended to continue the trek to the edge of Tibet and were infuriated to discover that we had been given the wrong permits. I can’t remember now how these permits were policed, but evidently we felt we couldn’t ignore them.]

[On our way back we got lost in a rhododendron forest in the dark and spent a night out, very worried that we might freeze, but a double sleeping bag and a space blanket saw us through the night. In the morning we saw that we were only 200 yards from the hotel.]

[In Kathmandu we spent a week getting permission to go to Assam, a politically sensitive area, where Carol was particularly keen to visit a tiger sanctuary called Manas. We planned to ride East across the Terai, which is the lower part of Nepal, to Siliguri.]

January 3rd 1977

From Kathmandu to Hetauda. Such a lazy start packing the bike with most imposing pile of baggage. Then round the shops and we leave with no map and only the sketchiest idea of the route, so the climb to Daman takes me by surprise. Endless rough climb in first gear. 50 miles in five hours to freezing summit.[Looking at the map now, I obviously took the wrong road out of Kathmandu.] No desire to spend another night below zero, and over the top we go, to find cloud hanging all around. Exciting but very uncomfortable. Memorable scene of mountain top floating on cloud, and patches of red light as sun sets.

Downhill not much better than climbing but a lot faster. Heavy pressure on shoulders and wrists and palms of hands. Thumbs frozen. But as we descend in dark, air is warmer, no more ice and frost on the road and surface improves. At Hedauda there’s the hotel Rapti. Though there’s an argument next day about the 15/25 rupee room.

January 4th Hetauda to Lahan

Mostly on the Russian road – built in 1972. Indians say price was four times the cost of theirs. Stop to make breakfast at junction with small track, where buses bring local people, who gather round our amazing breakfast spectacle. We discuss problems of spectator crowds. First was Western Reserve dam, and a huge multitude of people gathered for a Kumba Mela, to dip in the waters and celebrate. Ox carts packed with families; grinning children packed in like melons. Brilliant colours. Noise. Confusion. People streaming in and out along the skyline.

Russian road good and uneventful. Then big roundabout where Janakpur road joins. Now on Indian built road and soon come to vast riverbed where bridge is still unfinished. Road disappears in mounds of rock and sand, and leads to a broad water crossing over rocks where I’m nearly swallowed by dips in the riverbed. My boots are full of water. Carol crosses after me carrying bedding (bare foot). Drop bike once in sand. Then back on the road.

Lahan. Mr. Ombrugah (who has spent three months in Canada and saved 13,000 rupees, and missed getting an immigration permit by one week). The crowd in the guesthouse grounds, and my antics in getting them to go away. Walk to the grog shop. Mr. O. asks at shop for old magazines, says any book you haven’t read is a new book. Breakfast at his home. Little boy comes over. “Uncle, please come for tea.” Mr. O offers my cigarettes to his colleague – the general accountant. After this, long process of getting petrol.

January 5th, to Dharan

Difference in quality of road versus Russian built is very marked. This one sags, pitches and rolls. Every culvert is a bump. Lots of patching already.

(N.B. Col. Scott says Chinese road which runs north from hwy between Dahran and frontier has best reputation.)

[In Lahan we were surprised to find an army base for Gurkhas, with British officers. When I explained that I was with the Sunday Times, I was received by the officers and we were invited to drink gin and tonic with the Colonel, who wore a uniform made rather dashing with a coloured sash of the Gurkhas. He explained what the Gurkhas do.]

Brigade of Ghurkas: Capt. R.A.L Anderson, Lt. Col Scott, and Ringit Roy M.B.E

75 bed hospital, 30,000 patients annually. X-rays, Path lab, Maternity, General.

Camp has a golf course, two pools, tennis courts, etc. Some three dozen British. Staff of Nepalis. Brigade strength now down to 6000. (From 16,000 in 1968). Recruit a few hundred each year. Trained in Hong Kong. Distribute pensions to retired soldiers & widows. 130 Gurkan welfare centres. Ex-army men offer advice and assistance to resettled Gurkhan communities. Water supplies, medical care, co-operative management. Set useful example to surrounding communities. Benign infiltration, channeling of private funds (i.e. Canadian government matches charity funds, all for use of Gurkhas. Also help with building, farming, etc.)

Thanks for following along, Hope to see you next week.