Articles published in October, 2025

Chased out of Tunis by the police, and heading for Libya.

Tuesday 23rd October

Drive through Tunisia. Wet. Confusions at Sousse. Wrong name for the train conductor. On to Gabes. Hotel de la Poste. Letter to Peter. Right or wrong? Frenchman at Atlantic. Was there in war to put up radar station. Germans no good at electronics – except Siemens. Italians did nothing for the Libyans.

The coliseum at El Djem

Floods. Road cut behind me. Sousse. The Alaba? Hotel. All hawking and spitting. Good restaurant by the roundabout. Room was I dinar (£1) Remember how I was cornered with the bike in small gateway at back and forced to bargain for parking. I didn’t even know there were people sleeping under all that plastic at the back until next morning. I wonder whose lodging was more profitable – the man or the motorcycle?

Remains of a Roman aqueduct

[There are some days here I can’t account for, but I arrive eventually at the frontier with Libya. It’s not long since Colonel Gadaffi (or Quadaffi) seized power.]

Libya, Sunday 28th

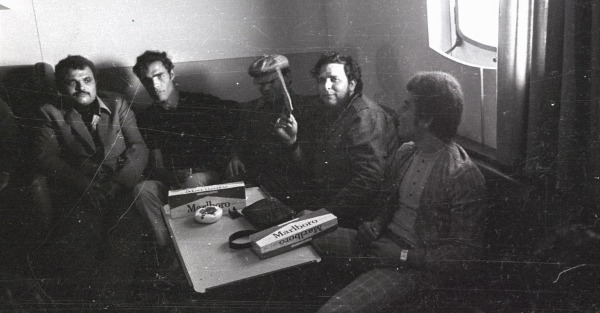

Police. Man with shotgun. Chief in his shiny Italian suit and suave grin, with carton of Marlborough under his arm. Customs man. Other man who came in to do police forms and passport.

“Helt?” he said. Oh, Health!

Sheets of Roneo’d forms in Arabic. No communication, but goodwill.

“Whisky?”

First taste of Libya, all Arabic. No alcohol. All fizzy water and Pepsi. Night on the dunes. Chakchowka [?] Coffee. Tent tied to bike. Lightening at sea. Then in morning, rain. Will bike fall through the tent? Will I be washed away? Frenzy of packing as huge black storm cloud piles up behind me. More sand than tent in the bag. But bike travels well over wet sand. Hooray for Avon tyres. But what hard work. And what did I lose in the process? Nothing, as it turns out.

On to Tripoli. Totally at sea with Arabic signs. Can’t distinguish one sign from another. Ask a driver for “hotel?”

“Follow me. I have time for you because I see you are lost.”

Customs took half my Libyan money. Hotel costs two and a half Libyan pounds – that’s over £3. Money is going at a rate. Meet Yorkshire engineer. Walk to the esplanade. Port full of ships.

“Been there for weeks. Port is too small. Can’t turn them round.”

Hotel full of roughneck Italians. Pipelaying gang reading comics. Not a woman in sight. In the street occasionally see bulky objects swathed in ‘Barka’, one eye showing. Mustn’t look at them. Who would want to? City looks full of bomb sites. Arrived at 11am. Spent most of the day sorting out mess from the night before. Into the shower with the tent, washing sand out. Dry it on balcony. Boots sodden.

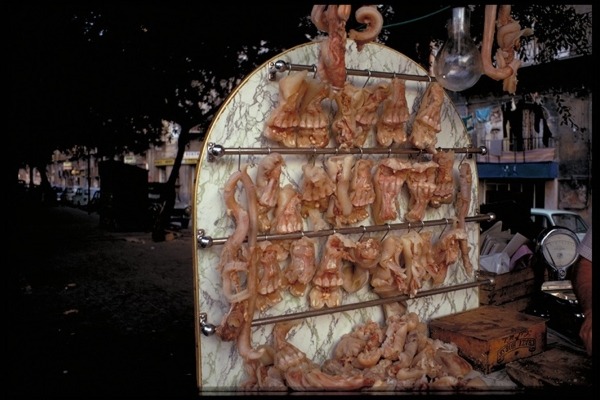

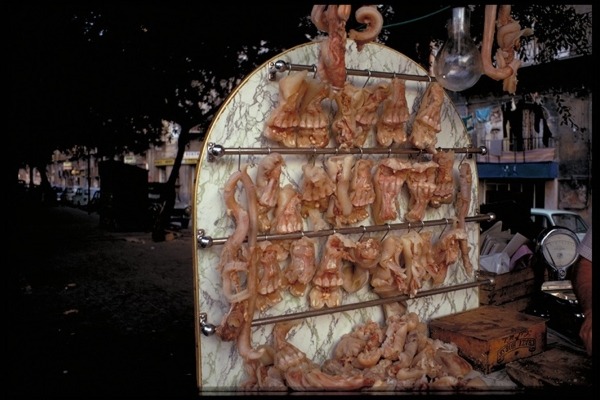

Don’t dry till next morning. But dubbin goes in well. Market is full of transistor gear. All looks like rubbish. In fact it’s all very rubbishy. Not a pretty object in sight.

Amin [Uganda president] is in Tripoli. Appears on television, like an ape-man.

In the morning, the bank. Soldier, shabby, hairy, with gun. Stout Arab is at the cashier. Behind cracked glass three men are all engaged in counting his money. He has brought a stack of notes over a foot high. And all in fives, tens and twenties. They count them again, and again. Holding bundle with one hand, flipping notes sideways with the other, looking around and smiling at friends, losing count and starting again. Twenty minutes goes by. Rain still bursts down sporadically.

Off at last. After eleven. The road to Benghazi. First, olive groves. Small trees. Then thousands of date palms. Dates light brown clusters at centre of palm – like dead leaves. Occasional camel. Settlements, earth confined by mud dykes. Wells of curious shape. Why the steps? Tried to ask the man here at hotel. Yes, he said, it’s like this. The road from here is good for 250km. Then there’s a very bad stretch of 250km !!!!???? Indeed. And what happened to my bed at 75 piastres? One Dinar it costs me for an army bed. But I digress. This is no tourist country. Why should I complain about it? That’s how it is.

The desert. Wow! Really desert. Out for ever. Cloud. Sun. Rain. Blue sky. All at once. For hundreds of miles around. I’ve never seen so much weather. Part of it’s dry. Groups of camels gather by the road. Frightened by noise, but shrubs grow greener at roadside. Pictures. Camels in haze of sand. On and on. Sand drifting across tarmac makes patterns like flames in fire.

First mechanical trouble. Throttle is stuck. Can hardly move it up. Won’t slide back. Have to cut off to slow down. Get to Ben-Gren way station.

First signs of trouble. Air filter inadequate.

Two Egyptian labourers help to move bike into shelter where I clean sand out of carburetor. This is going to happen again. Get a plate of spaghetti – young fellow, son of owner, speaks English. He gives me the food. Take pictures again. Also took pic earlier of – Septis Magna – was it?

Police stop me once. Go through my papers. No question of insurance, though. Drive on as sun dies behind me. Into the gates of hell. Huge storm blackens sky ahead. Seem to be always driving into the worst weather. Altogether this journey feels like that. Sort of apocalyptic. Like Frodo going to the dark country.

After the storm, road suddenly barred. Diversion points out into the desert. Can’t see a road. Decide to ignore sign. Tarmac continues, very broad, almost like an airstrip. Is it? Nearly at the end, car full of soldiers comes weaving past and stops me. Examine my passport upside down, very earnestly. But always with good humour. Police and soldiers shake your hand afterwards. Wish you well. On into the night. Feel good, alert. Ready to drive all night, but stop for petrol at Sirte, and soldier says I must go to police. Evidently, they don’t like people out at night. Have to stay at this hotel. Rambling building. Group of Arabs in fez and pyjamas sitting in one corner smoking and drinking tea. Those famous pyjamas. Desert dogs look white and handsome. Ground in Libya looks as though it’s had the top ripped off – like bottom of a disused quarry.

Sirte is a sea of wet sand. But everywhere among the broken buildings, the rubbish, the peasant shacks, are new cars gleaming. Black and white taxis drive up to the poorest buildings, rush up and down the highway – big Peugeots, Mercedes, Datsun trucks, Toyota rovers. And everyone seems to have a stack of those big banknotes, to make me feel poor, underprivileged like a newly arrived Pakistani.

In this weather the tent is almost impossible to use. Hotels break me. Only petrol is cheap, thank God.

Oh yes. Big tents in the desert, usually near a village. Like marquees.

Lousy desert picture, but it’s all I’ve got.

Tuesday, October 30th

Left Sirte at dawn. Clerk sleeping in his clothes by the door, wrapped in a sheet with light on, his white fez by his couch. Arabs by the car-load continuing their journey. Rain goes on. Very heavy for three hours. Can’t believe the bike won’t stop. God bless Triumph, and Avon – and Lucas. Stop for petrol at small place before Sidr. Cup of mint tea, packet of sweet rolls. Bartender takes 10 p. Must have cost more. Had two shaky moments on mud ridges dried hard and then wetted down. Was into the second before I realised what the first had been.

Absolutely soaked. Boots squelching. Crutch sopping. Then, at 10am, after 150 miles head down on tank, like a bullet at 70mph through downpour comes the light. This desert is not the desert of BOP, of Khartoum and Lawrence. This is a primaeval swamp and camels look like prehistoric monsters. Rivers gushing along the side of the road. More permanently garnished with shredded tyres and cautionary wrecks – road safety sculptures of cars frozen and rusting in the posture of collision. A deliberate warning? Or simply neglect.

The sky clears as I drive out from under the roof of raincloud. Stop. Walk in the desert. Picture of bike draped in clothing. Then on in sunshine. 100 miles from Benghazi, make coffee, eat sardines within 100 yards of tented encampment. But nobody approaches.

Next week: To Benghazi

I took the ferry from Palermo to Tunis.

Sunday, October 20th

For some days I’ve been travelling on the brink of Africa. From London, perhaps, Tunisia seems no great distance, just a package flight away. For myself I can only tell you that after 2000 miles travelling towards this immense continent, speculating on what lies ahead, I feel a very long way from home and, in quiet moments, alone as though I were about to step off the edge of the world.

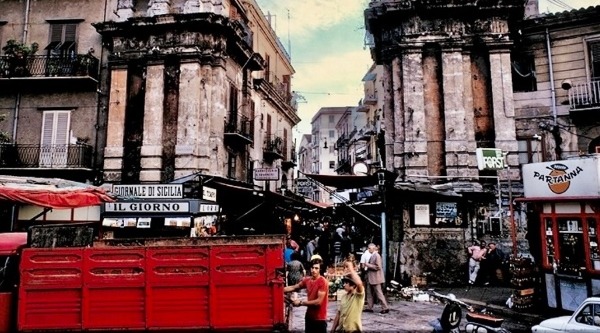

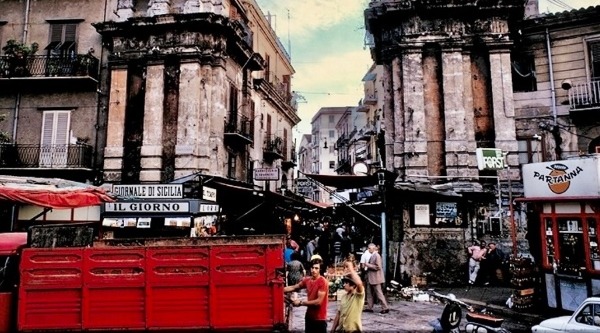

Goodbye Palermo

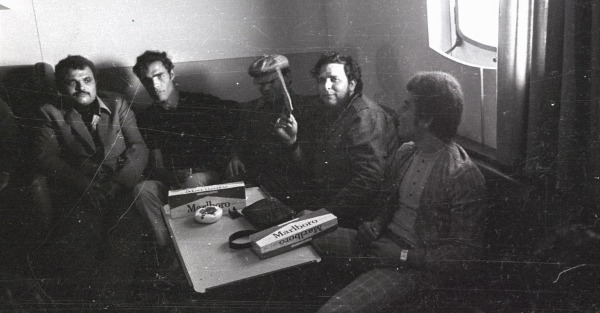

The boat left at 9.30 – a fine looking, modern boat, with drive on facilities, called “Pascoli.” On the deck met two somewhat effete Englishmen with a Renault, driving back to their home in Tangier. I still seemed a long way from the kind of Africa I was expecting. On the boat, in the plastic lounge, was robbed for a beer. I met the Tunisian from the market yesterday, but he failed to make much impression because with him was the man who became the pivot of the ship’s life for most of the morning.

He was chubby, Castro-bearded in a green tunic (US style). Shock of black hair at the top, pale skin wrinkled by much facial work. Coconut shaped head. About 30 years old. Started by being merely noisy.

The poet is waving a paper in front of Mohamed’s face

“Ah you, vous, wass machen, sprechen Deutsch. Ich auch. Scheisse.” Burst of Arabic. “Ich bin Hamburg. . . . “ and so on. Then he started singing. Gradually he drew his audience around him. Singing and clapping. Soon he began to formalise his act. And from buffoonery he moved to love poetry and then an extraordinary declaration on behalf of Bourguiba. Much of this I have on tape. The train driver from Sousse translated and gave his view.

“At first I thought he was a fool. But now what he says is really impressive. It is realistic and good sense and very poetic.” Much of this is on tape and performer’s address is in the book. Took B&W pics but quite dark and will need pushing through.

[I was still planning to send tapes back to the London radio station.]

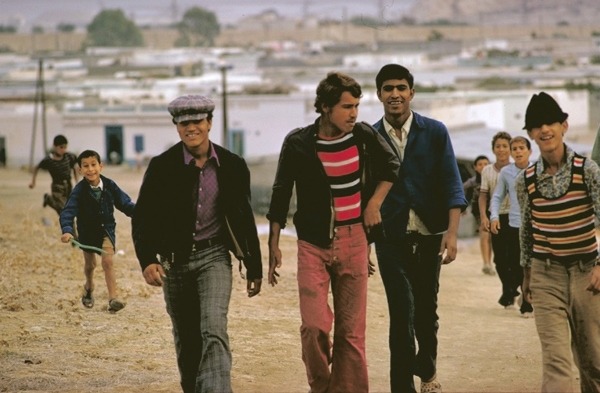

Singing along was a young handsome Arab with a peaked cap and smart jacket. He also was very friendly and although his French was worse than the other’s he persisted and invited me to his house. I followed the taxi round Tunis and then through an open dark area [night was already falling] to the Cité Nouvelle el Kabbaria. Blocks of plastered brick, 1 storey high. No window. Set down in rectangular arrangement on stony ground.

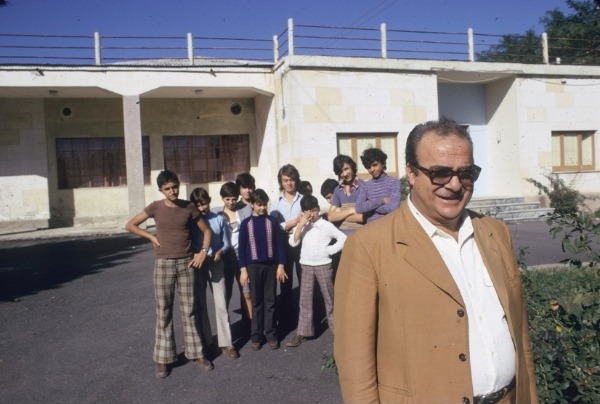

Mohamed (left) and friends

In No27 Rue 10083 lived Mohamed’s family. There are 9 altogether but only five of them live here. Two small kids and parents. Father, red fez, trousers and shirt, runs a tabac. So he has a room opens onto street, with a counter. His tabac is lit by a Japanese paraffin lamp. Mother smaller, and similar to Algerian ladies in Lodève [my nearest market town in France]. Five children. One other daughter married and pregnant. One youngest girl and three boys. The two small ones are barefoot, very appealing, curious, active. At night, with light and shade so mixed, it’s hard to see the building as a whole but in the morning I see.

In the back room, which is Mohamad’s, a sumptuous looking bed draped with a cotton pile rug in shiny floral pattern. This seems to be the only bed in the house and is offered to me. I am not quite able to subdue my imagination which still suggests that I have fallen into a cunning trap, partly because I’m set down on a chair in the bedroom while whispered conference in Arabic outside. But commonsense tells me this isn’t so. Shortly, I get up and walk into the courtyard, but some residue of suspicion must have shown in my movement or expression. Mohamed said I could come and watch the motorbike if I wanted, but it was all right. Slightly shamed I returned into the room (which was never more than a few feet away) to find that a dish had been laid there with bread. Two small lamb chops in heavily spiced hot sauce with peas and a pepper. No cutlery. Got my hands messy trying to scoop up the sauce and peas. Couldn’t finish it – too hot. Felt bad about that too.

Wanted to let M sleep in his bed. “Whether you sleep in it or I it’s the same thing. If you sleep in it, it is as if I were sleeping in it.” The Arab formula was not florid lip service to some tradition. It was real and meant. No doubt. Although the bed was a doubtful privilege. Couldn’t sleep for ages, with tickles, particularly on my hand. Lay on the rug with a sheet to wrap around. In morning enormous numb swellings on my left face, neck and right hand. All out of the sheet. Felt as though some fearful African leprosy had struck me down already. Of course they must be bed bugs. But WHAT bugs!

In the night someone processed in the street beating a soft drum at slow march, missing an occasional beat. He was announcing the time to eat for Ramadan – before the light at 4.35 am. For these are the last five days of Ramadan. And Tunis has an Italian fairground to celebrate it. No eating, drinking during daylight.

Remark by Mohamed, “Mon coeur est blanc” – “My heart is white.”

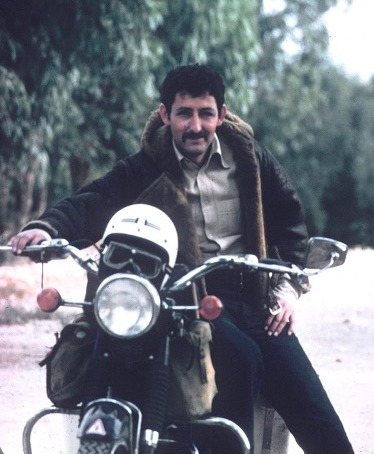

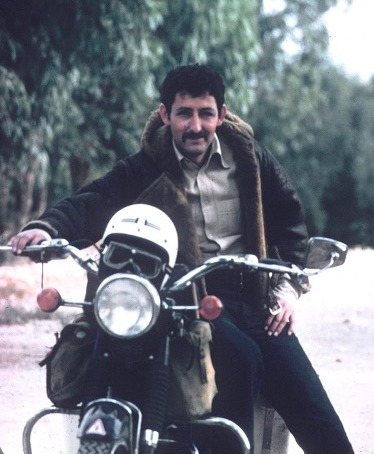

How I looked then

Monday October 22nd

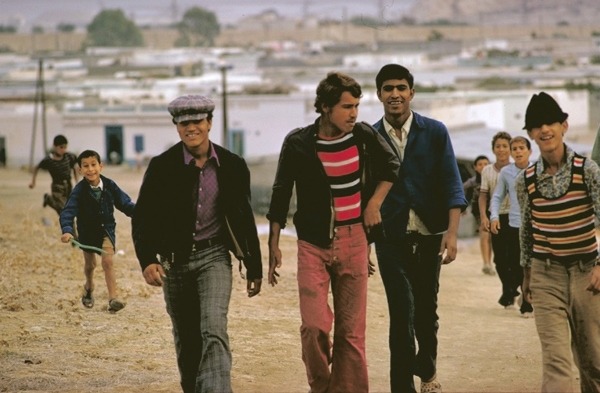

Went to the ‘forest’ – a sparsely wooded slope leading to a beach where “all of Kabaria” sits in the summer “to admire the view and the trees and the flowers” with Mohamed’s friends and brother. We took pictures of all of them sitting on the bike in turn. These I hope still to have, including a “Magnificent Seven” pic of them coming up over a hill.

No question, M is impatient with pix in which he doesn’t figure and has a star’s attitude to photography presenting his best profile (one cheek is scarred by eczema or acne). In a sultry mood.

In the evening, I took him to Tunis with some clothes for another sister, and her husband who mends watches. More appealing children.

We’re invited to lunch by M’s brother-in-law. He has a job, and has a prosperous look, confident, etc. Newly married, wife is pregnant. Sweet in pink gown, tight round her belly and behind. She has cooked some of the food that M bought at the market. Olives, pickled vegetables, salad – crinkly kind – grenades. No plastic. Thick paper wrapping.

[They took me to visit the brother-in-law’s father, a traditional country “paysan.”]

The oven where they bake their unleavened bread

The brother-in-law’s father’s homestead. The bread oven, cow and calf. Beehive. Cactus hedges. Story of Jewess who has children by the man who killed her husband. “Beschwaya, beschwaya, wait and see.” [Slowly, slowly. She teaches her children to kill him.]

“Jews smell,” he says. Clean area. Charcoal brazier. Couscous with chicken. Powerful tea. Old man’s feet. Face. On bed smoking. Wife always behind me. Crouching over fire. Bread and honey. Leave after dark.

The day at Libyan embassy. The “jailor” in fez. People all living in one room. The desk clerk at Hotel Africa. “Arabs don’t know how to make politics. Here’s the round table. Here’s a general, a king, a dictator, a democratic president. They never agree. So they can never bring force to bear. Always arguing.”

Tuesday 23rd Leaving El Kabaria

The final incident. Pied piper leads huge hoard of children and people. M swinging the camera. Police. Film exposed. Humiliation. Departure. What did the police tell him?

[I had no choice but to leave in style, with half the village trailing behind me, but two ugly-looking plain-clothes policemen came to break it up – threaten the people, seize my camera and open it to expose the film, then accuse me of whipping up a mob for my own dastardly purposes. Tell me to get lost. The following picture of Mohamed’s father in his courtyard just survived.]

If you read last week’s notes about Zanfini, you would probably like to know what became of him and his project. I returned to Roggiano in 2001 and wrote about it in Dreaming of Jupiter. I have reproduced some of that at the end of this week’s notes. For more you might like to buy the book.

Friday October 19th , Leaving Roggiano

Now just a matter of making distance to get to Palermo. Have only a sketchy idea of distances in Sicily. Think it’s pretty small. Partly the effect of Mercator’s projection, but mainly through insular whim concerning islands.

Ferry crossed from Reggio to Messina at 3 –3.30 pm. Cost 700 Lire (150 for person) Carries trains and cars. Rails on wood warped into barrel-shaped sections between rails. At other end, straight on to promising Autostrada missing Messina altogether. In the event it was 150 miles of which perhaps 25 were motorway, the rest sinuous coast road with patches of “original” Italian road surfaces. One and a half hours of daylight driving, three hours in dark following a car or a truck. Into Palermo itself, a half mile of cobbles. Arrive at 8pm, very far gone.

Mentally, when I get off the bike after a long ride, although capable of thought, I feel almost incapable of initiative. I want to reach immediately for the nearest source of rest, food and security. And this is where the act of motorcycling can impose an unusual perspective on life. Can make a prince feel like a peasant.

First of all, it is almost impossible to ride hundreds of miles with traffic without getting filthy and feeling it. Second, and I speak now about cities, you can’t leave the bike. Assembled on it is your universe, a natural target for thievery. Like a Christmas tree it glitters attractively and has presents tied all over it. You and it must be inseparable. You can’t lock up your car and melt into the crowd. You must attract the crowd, and the crowd becomes your enemy and your salvation. Because somewhere among the curious children and adults is someone who will help. But who to trust? How to convey your meaning with few words in common? All these things require patience, reserves of goodwill and imagination, which are precisely the qualities you’re least able to call upon. In summoning them up you dig into your own personality and painfully a sort of truth emerges which represents you, not as you would like to be seen, not as you think you ought to be seen, but as you are.

October 20th, Palermo

Yesterday I arrived in Palermo slack of face, filthy of garb, and reached immediately for a telephone to call the friend of a friend. Then sat in a bar and waited. Why did the large, fat man sitting outside playing cards warn me to keep my eye constantly on the bike? Why did he want to help me find my friend? What about the Israeli who came up and said he was trying to find out whether he would be jailed if he went back to Israel now? What about the German-speaking waiter? Wouldn’t any of them have helped me towards food, bed and stable? I was glad to have my friends, to be taken to a grand restaurant, fine pasta and grilled fish. What did I miss?

Today I can view Palermo as a tourist – but last night, on the via Torremuzzo, I saw it as a film by Visconti or Fellini – a set piece of villains, freaks, saints and brawlers in the night.

Priorities

1. Ferry booking, Peter Harland, LBC, ST Notes and film, Triumph diagnosis.

This is a coded inventory of anxieties. I am obviously destined to live with them for a long time, but it contradicts the habit of a lifetime. Somehow I will have to learn to enjoy what my senses can grasp and not draw them in like a frightened snail until I’m sure it’s safe outside. Is this possible at the age of 42? I’m definitely up against time now – time spent and time to come.

2. Will the Tunisians let me in?

How will I recover my deposit from the piratical Tirrenhia [The shipping company] if they don’t? What on earth will I do if they don’t?

3. Why is the Sunday Times telex number wrong? UK MOTNE LONDON indeed!!! Cost me 500 lire for a nonsensical waste of time.

4. Will I ever get through to Harland?

5. Is there something very wrong with the bike if it does three pints in a thousand miles? Obviously.

6. Can I cure it alone? So on and on.

Each problem solved opens doors to new ones. I must find it in me to go on solving them and still say – To hell with them! Obviously though if I’m to keep going on the money I have, I must keep out of big cities most of the time.

[A week or so before leaving England, Harry Evans, the Editor of the Sunday Times who also rode a bike, arranged for us both to get schooled by the motorcycle police. In those days it was still a rule to give hand signals.]

Sergeants Farmer, Fittal, and Easthaugh, I’ve been thinking of you. Every time I take the wrong line on a bend or find myself hopelessly confused between wanting to twist the throttle and signal with my right hand; I feel your eyes heavy but benign on my neck.

“He’s a good lad,” they say. “He’s trying, but he’ll never be one of us.”

Who are those three dashing sergeants? They are all at the police driving school at Hendon, and I was privileged to spend two days with them before leaving England, to see what motorcycle policemen are made of. The experience had a profound effect on me, which extended far beyond mere motorcycle matters. I learned for the first time in fifteen years of miscellaneous driving what that boring old highway code was really about; what it feels like to be safe on the road. As a motorcyclist I feel much more competent to stay out of trouble, but if only car drivers could get just a glimpse of the dangers of the road as a motorcyclist sees them, I would be elated. I include myself. Three months before leaving on this marathon I was an ordinary driver on four wheels. What I did then makes me shudder.

For one thing, car drivers fondly imagine that a motorcyclist can always squeeze by somehow. In fact, on two wheels you take your life in your hands on many roads going to the edge to avoid a road hog. On country roads particularly where there is often loose grit or gravel at the edge. I’ve fallen twice in this way, fortunately at slow speeds. Once at high speed and face-to-face with a four-wheeled assassin filling my side of the road I was just lucky.

Then car drivers suppose that other drivers trust them to do the right thing. On a motorcycle you dare not trust anyone. If you see a car rushing up towards you on a side road, you can’t afford to assume he’s going to brake at the last moment. And the avoiding action you take, whether you brake, swerve, or accelerate, is likely to carry its own risks. Car drivers who signal badly, or not at all are a hazard to all traffic, but to motorcyclists they are positively lethal. And so on and on. . . . . .

[Well, here endeth the lesson. I don’t think even police riders do hand signals anymore, and my feeling is that car drivers are generally more controlled today than they were then, more by regulation than by themselves. But you still dare not take your eyes off them.]

I wanted to reproduce here what I discovered in Roggiano in 2001, but to my surprise and disgust Adobe has locked me out of the pdf files of my own book, and I have no time now to sort this out. Suffice to say, when I arrived Zanfini had been dead just a few years. A school in Roggiano had been named after him. His widow was curiously reticent to talk about their history. I formed an opinion, quite unfounded, that there had been some strain on their relationship, and that it might have had to do with the young woman dressed in black, who had so impressed me when I first arrived. At any rate, Zanfini appears to have succeeded with his program, and was well remembered, but the buildings so ardently created, were now obsolete and derelict.

Cheers, everyone, until we meet again.

Ted

On October 18th I was still making my way down Italy to Sicily, and the ferry that would take me to North Africa. With my eyes firmly fixed on the unknown world ahead of me I wasn’t expecting to experience anything much worth recording, but in Roggiano, Calabria, I was reminded that the adventure can begin anywhere, when Giuseppe Zanfini made his operatic appearance in my life.

Please read last week’s notes first if you haven’t already.

Here’s what I wrote in my notebook:

“When I was eighteen, I was a fascist from my eyes to my boots.” His hands described the very ample parts of himself that included, but his plumply energetic features indicated that he was far beyond making excuses.

“I volunteered for the army to go to war. I was in officer school. Then in Sicily, four years after, came my first real battle. I heard the toot toot of the bugle “ – he went toot toot – “that meant go to prepare arms. I was in the tent to pick up my gun and clean it and I thought, this time it is not for a paper cut-out figure. This time you will have to kill real men, and I knew then that I couldn’t. Not to kill men with mothers like mine, with children – men who come from homes like mine which will be in misery.”

Short of wringing tears from his eyes Signor Zanfini relived his moment of conversion in front of me, behind his office desk. In a measured hush he spoke of love and brotherhood, his face flitting between solemnity and ecstasy. As the battle progressed he wiped blood – the blood of other men – from his face. He represented graphically how other men had lost a hand, an eye, a leg.

“After the battle the Colonel wanted to give me a decoration because I had stayed on my feet through the battle, but I refused. I told him I would never bring myself to kill another man. He said he understood but asked me only to keep my sentiments to myself. Three months later was armistice and the colonel was able to sign my permission to go to university. There in the new democratic Italy I studied to become a teacher and came home to Roggiano to teach others that we must have peace not war.”

“Then I saw that our men were returning from the prison camps and talking to their families at the fireside about the war. And then soon the children in the square were rushing around saying ‘Bang, bang’ and ‘Boom, boom’ playing at war. And I saw that although we had already lost one war, we were in danger of losing an even bigger one around the hearth.”

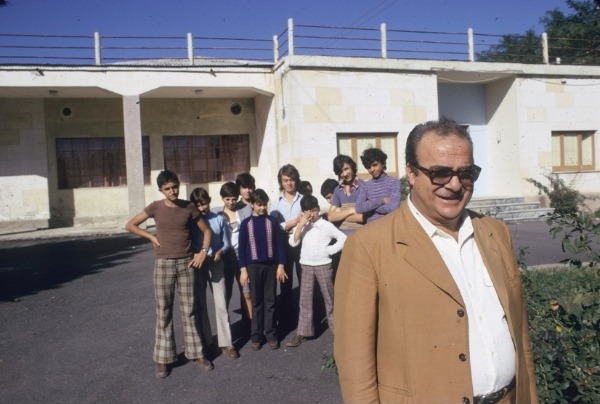

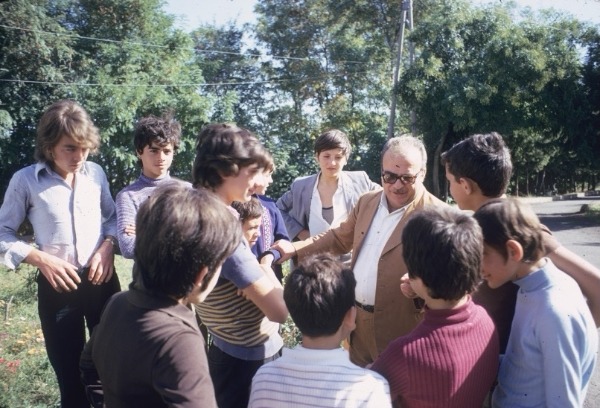

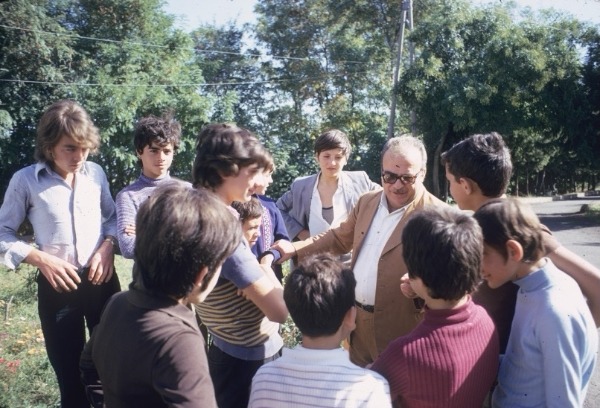

Zanfini was determined that children should not grow up to worship war. He propagandised ceaselessly, in school and out. In 1949 he joined in with the illiteracy campaign to open a small cultural centre in Roggiano. Nearly fifteen years later his energy and imagination (supported by his undoubted dramatic ability) has had great influence. It has drawn visitors, expert and student alike, from 84 centres to watch signor Zanfini’s cultural program at work in a peasant community. Both Swansea University and Manchester (through Prof. Ross Waller) have a permanent connection with Roggiano and send many students from undeveloped countries who may see how to tackle similar problems in Asia and Africa.

Because Roggiano is in Calabria, the heart of the Mezzogiorno and, at the end of the war, still largely cut off from the mainstream of European thought and progress. Now Zanfini is at the point of seeing his last and most extensive project realised. After seven years of bargaining and persuasion he has brought the mayors of the fourteen communes of Esore – seven Christian Democrats, four Communists, three Socialists – together to agree on one school for the whole region. A school not just for children, but for adults too. A centre where the skills learned by the children can be put to use by the community, where chemistry students can tell the peasants what their soil needs, etc.

He unfolded his plan and pinned it to the wall.

“All this,” he said – and there was a lot of it; some thirty buildings or more, with sports stadium, pavilion, theatre, and so on – “all this will cost only an eighth of what must be spent if each of the communes were to build their own necessary schools.

“Yesterday I had the councilors of the Regional Government of Calabria here to make their own final decision. They have agreed that it must go ahead. Now all we are waiting for is Rome and the law. The principle of comprehensive education was already accepted by the previous minister of education. But even if the Government said no, the people of Calabria would be determined to go through with it somehow.”

“Another march on Rome?” I suggested jokingly.

“No,” he said. “Never. There must never be another march anywhere.” And that same ineffable sweetness flooded his face, which only in Italy could carry conviction. “Peace and love. Love and peace.”

Now that he’s fifty he’s ready to retire. Area involved about 60 Km X 35

All decisions on community centre are unanimous.

Friday October 19th

Took pictures of Zanfini on 28mm lens. Then usual hour to pack everything. Got away about 10.30. Changed money in Roggiano. Every time the rate gets worse. In Rapallo 600 lire per $, in Rome between 583 and 575, in Roggiano 565, a 6% drop in value. What will it be in Palermo?