Articles published in December, 2025

Thank You Very Much

First of all, I want to acknowledge the response to my offer of a One-time Subscription. It has released a small flood of generosity which makes it plain that over time I have established a place in many lives. Not just through this series of travel notes, but in some cases going back through decades. Although I deliberately avoided pinning my appeal to any future book, I do now also have the beginnings of an idea of how to use these notes as a truly valid companion to Jupiter’s Travels. I’ll be developing these thoughts as this series draws to an end this coming summer.

From My Notebooks In 1973: Aswan and Lake Nasser

Finally convinced that there was no hope of getting permission to ride up the Nile, I bought a train ticket to Aswan. I had become close to Amin, the hotel manager, and he confided in me that he was planning to escape from Egypt and go to Brazil, where he already had an older brother, a doctor, established in Campinas, near Sâo Paulo. Legally, he was supposed to do years of military service first, so he would have to leave only with what he could carry. He asked me if I would carry with me, on the bike, his father’s ceremonial sword and deliver it to his brother when I arrived there. I was touched by his confidence, and the sword, in its scabbard, took up residence alongside the umbrella.

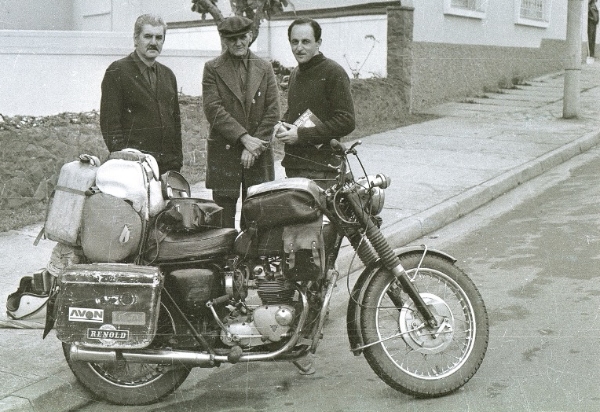

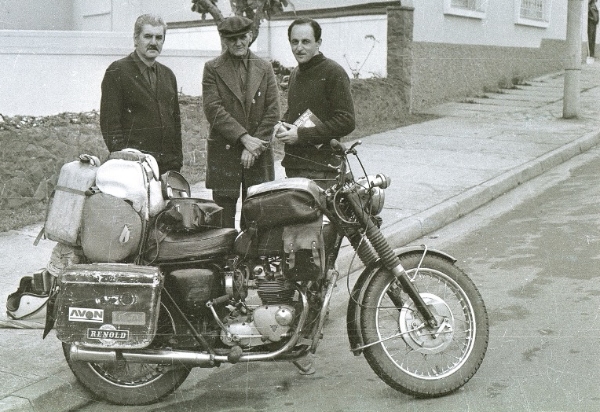

I got to Campinas nine months later. Amin had already arrived. That’s him on the right.

And this was me, holding on to the umbrella.

Meanwhile, back in Cairo, Monday, December 3rd

The train to Aswan. Cairo station – traders, stalls, cattle, crowds of persons waiting to coagulate round any seed.

Two references from Faris Serafim [Proprietor of Golden Hotel, Amin’s uncle]

Moatassam Bereir, influential, Khartoum, Foreign Office.

Mohamad Abouleila, Khartoum, Good family, older brothers know Faris.

[I did what I could to secure the bike and, with serious misgivings, entrusted it to the baggage wagon. The train left at 8pm. I was in a compartment with two Egyptian families who spoke almost no English but they had quantities of food for the 16-hour journey which they shared generously with me. We slept in our seats. In the morning I got breakfast in a saloon car and watched the passing scene. The train travelled very slowly, stopping often.]

Company [of conscript soldiers] descends at Essna. [Reminded me of my own national service.]

Just like UK conscripts being shuttled about, showing no sign of anticipation. Wear heavy khaki like us, plus suitcases, etc.

[Looking out at villages.] Stuffed animals over doorways, lizard, a fox.

[I had thoughts about the evolution of pyramids. Why that particular angle.]

My pyramid theory. Natural form of erosion in Upper Egypt. Rocks have caves in them. Measure angles, etc. Maybe some corpse was found in a cave in goat milk. [What was I thinking?]

In front of some villages, stones stood on end, curious effect immediately noticeable, but why? Not big stones, and all shapes, six inches to a foot, but all unnaturally upright. Still don’t quite know how water wheel works. i.e. don’t know what it discharges into.

[The train stops.]

Three peasants working on a plot of earth beneath window of train. As usual earth divided up chessboard fashion with foot-high dykes around 3-metre squares. Two men were chopping vigorously at earth, one old, one young.

The old man was tough and skinny and wore absolutely nothing beneath his galabeia which became evident when he bent down towards the train. Standing by them, with a five-foot cane pointing at the earth was the most imperious lady I have seen. The mother of all the pharaohs. In black, with black headdress, old but refined, face as strong and vigorous as ever. Tall, straight, irrefutable authority. Head a perfect long oval, mouth in parentheses which seemed on the point of curling down in contempt.

Tuesday, December 4th

Train empties at Aswan and waits. Then on to lake. Unloading is easy enough, though the attendant stands studiously while I hump my bags, then solicits a tip (which I give him, salving my pride by halving it.) From the platform have to drive bike down some steep steps. I let go a bit soon and on the last bounce I lose control and fall into bushes. Malesh!! Short and ineffectual interrogation by soldier, and I follow my self-appointed guide (an Arab Merlin figure) to the stony shore where some people are gathered outside s group of shacks, milling about among bundles. I have a ticket but must pay for the motorcycle. There is one shrewd fat Arab sitting outside a cabin, surveying the mob, while his men work. I give them the correct weight of the bike. and they charge me E£5 without weighing it. Passport control is simple, and the vehicle control looks straightforward, but I’m beginning to wonder how I’m going to get my bulky objects through customs, which is besieged by camel drivers carrying huge canvas and leather bags which I presume they sling over their camels. The carnet man indicates that an amount of money will help me over their problems and I succumb, with half a pound. In fact, if I had known how useless my pounds were to be I’d have been less precise. However, I was through and down to the boat in a flash and forgot completely about changing money.

The problem at the boat then obliterated any other concerns. It was immediately clear that it would be [all but] impossible to get the bike on the boat because my boat was separated from me by another boat. [They were parked side by side on the embankment.]

The first problem was the conventional one – of lifting four cwt down three feet, then to manoeuver it through a narrow passage packed with camel drivers in a terrible hurry. While manoeuvering it round a sharp corner all I lost was one pannier. It was just a matter of persistence. But the final crossing [to the other boat] was inconceivable. Both ships had steel-sided gangways, with openings only wide enough for a person, and the openings did not coincide either with each other or with the end of the passage. The bike had to be manoeuvered through a Z-shaped path, in mid-air at an angle of 30 degrees pointing downwards across three feet of water.

But for the sky-hook that appeared halfway through I think the journey would have stopped there. Even so the bike was resting most of the time on the remaining pannier or the foot brake pedal, which assumed a distinctive slope. There were five people struggling, and I was least use since I couldn’t understand the others. Finally the project passed out of my control, and I had to hope for good luck as I saw the exhaust manifold within an ace of being ripped from the cylinders. The experience affected my view of the boat, which I saw as cramped, dangerous, expensive and inhospitable. The deck, which I had imagined open to the sky, with chairs, was below with no chairs, or indeed anything but refuse and bare steel. Some cars had been brought on from the other side when this boat had been against the bank, and filled most of one half. At the other end, behind some corrugated iron, was a man brewing tea. A desk in front sold chits (or scrip, or torn bits of used paper) but of course took no Egyptian money (except from Anthony because he’d paid for first class.)

[Anthony was a young Dutchman, travelling with his wife.]

Every other floor space, except for a narrow footpath, was resolutely occupied by camel drivers who had their bed bundles down while I was struggling [with the bike]. As the journey advanced it became increasingly difficult to distinguish the people from their luggage. The grimy galabeias merged and an occasional limb or head protruded here and there. Most of them stayed, scarcely moving, for three days and two nights, while drifts of scrap paper, cigarette ends, orange peel and dust, all bound together with spit, built up around them.

The sight of people letting loose a jet of spit on the floor where they sleep is so objectionable that it goes beyond disgust to sheer wonder. How can they? But if you consider the desert your natural home (where spitting is not only harmless but quite natural) then being inside a house or boat is scarcely significant. Considered alongside the meticulous and lengthy rituals of spiritual cleansing which these same drivers undergo every day, it is hard to say who comes cleaner out of the wash – they or the European.

Two nights and three days floating across Lake Nasser.

A view of the first class boat from the third class. I soon joined them, on the roof.

It became clear that there would be no room to sleep even in these conditions, but the other boat which was all but empty was said to be for first class only. However, Europeans obviously have a natural exemption to class restraints in Africa. Should I have stuck with the drivers? It was not a productive thought. Other Europeans would not have allowed me even a faint chance of an understanding with them on such a short journey. I smuggled myself instead on to the top deck of the first-class boat, and I slept out under the sky. Bright moon. Stars becoming familiar. Cold at 3 am but not too much so. Spent time talking to Australian Mike – Macdonald. Something about him remained alienating to the last. A conflict of styles? His funny hat – a Moslem cap – was aggressively incongruous. The forthright manner was not quite true – and concealed a complex and uneasy personality. Protestations of easy independence were contradicted by heavy point-scoring humour, and he lost few opportunities for self-congratulation. Yet there is a wistful, touching desire to find peace with himself (which he failed to find in his monastery.)

Although the Dutchman wielded an equally heavy sledgehammer, he seemed to have found more peace in his 26 years. He and his wife Alice were travelling to South Africa to visit her father (?) It was her idea. He had wanted to holiday in Norway but now he was finding much reward. His treatment of his wife was very masterful, and she was obviously devoted to him, even when he scolded her like a father. A big man, studying “marketing,” son of an old family, with a natural confidence which could make him boorish and pigheaded, but for the moderating influences [of his wife] which he is happily able to accept. He was taken by my idea of classifying people as “alive or dead” but said he would have to study it.

Train from Cairo 7E£n+ 6E£ for bike. Left Cairo 8pm. High Dam 1.30pm Boat from Aswan to Wadi Halfa 2E£ 3rd class + 5E£ for bike. Spent E£5 on boat. Train Wadi Halfa to Atbara 3.60 S£+ 3.61S£ for bike (200kg)

Total £24 sterling.

I’m taking a week off, so in two weeks: Atbara and the desert.

Merry Christmas.

To my readers…

My quixotic notion to offer you an opportunity to reward me for the pleasure you have already enjoyed has provoked some interesting confusion.

A few seem to feel it’s almost immoral. “If I’d known I was going to be asked for money I would never have started reading your pieces in the first place.” Well, nobody actually said that, but I got the hint.

Then others thought I must be asking you to subscribe to a future book – I wasn’t – and refrained because they don’t think the book’s a good idea. Anyway, to those who simply thought it would be nice to give me something for past pleasure, thank you very much. I am quite comfortable with it. I believe I have earned it. And if I DO decide to make a book of it, the money will help. It was also a valuable experiment. It helped me to find out where I float in this ethosphere. Now, back to Cairo.

From My Notebooks In 1973: Egypt

[I’m desperately hoping to ride the bike up the Nile – such a vital, rich seedbed of humanity: Luxor and the Valley of the Kings. There’s a lull in the war. Why shouldn’t it be possible? In the meanwhile, I tried as best I could to understand Cairo. At about that same time it struck me that Islamic countries, from Morocco to Indonesia, spanned the globe, rather like a scimitar, and would be a mighty force if they could unite. I put this to a high-ranking journalist, Denis Hamilton, who happened to be staying at the Hilton at that time. He thought a minute and said, “No. The Shah would never allow it.” He meant, of course, the Shah of Iran. We know what happened to him.]

Cairo, 17th to 22nd November

Waiting for permission to ride to Aswan.

Daily round begins. Groppi’s for coffee, etc. Reuter’s office. The Press office at the Information Building, lunch, a game of chess and then anything to get the evening over with. At first, I think it will be just a day or two. My piece went off to London, together with a message, on Thursday. There was no reply, but the bureau lady has convinced me that because of my faulty slugging they may have got scrambled or delayed. So I repeat my message. [“Slug” was the word used to identify a piece of copy.]

Meanwhile at the press office Frau Amin treats me pleasantly enough and I am lulled by her comfortable conversation (which is quite genuine and kind.) although nobody thinks there is any possibility of my being given permission to drive to Aswan.

Meanwhile there are also the first set of papers from Benghazi to expect. And with Amin’s help at the hotel, I try to grapple with Libya and Arab Airlines, but they are too slippery for any of us. On Sunday I decide to cable Kerim for the waybill number, but the cables are subject to several days’ delay. The telephones however are working properly so I book a call for Monday morning. The days pass. I develop a powerful reputation for chess, dodge nimbly across the frontlines of affection between Amin and Alan and learn what I can from Faris Serafim. [Alan was a pale young Englishman with an upper-class accent staying at the Golden. Amin and I both thought he was probably a spy. Faris was Amin’s uncle who owned the hotel.]

Faris was at Oxford in 1919. I gather he read theology. He is, in any event, a Christian, i.e. a Copt, Egypt’s original tribe. He was contemporary with Nehru and, he suggests without naming them, many other luminaries. He recalls that they founded the International Club and toured Britain (Cardiff, Bradford) to speak in halls and churches about their respective countries. He considers there were some whose qualities were greater than, say, Nehru’s but rejected power when it was offered and contented themselves with being obscurely good.

He himself was from a family which had built a considerable position in Egypt. He talks of his great grandfather, who was “keeper” of the village in the reign of Mohamed Ali, and whose citizens hatched a plot to murder him rather than pay taxes. He escaped but the villagers claimed he had run off with their boxes, and a price was put on his head. He, however, made his way down the Nile and finally contrived a personal encounter with Ali when the guards were some way off.

“Surely you know,” said Ali, “that I have put a price on your head?”

“You can have it for nothing,” was the reply, “if you don’t believe my story.”

The upshot was that he promised to double the tax returns if he were allowed to found his own village, and he did so. This then became El Minya and the Serafims became very wealthy – sufficiently, according to Alan, to give a visiting Cardinal dinner for forty off gold plate. By the same source he is said to have been Egypt’s most prominent businessman, who was intimately concerned in and with the political structure of the country.

He knew Strawblow and the two men who helped him to the right hand of Durante and recounts that those two men soon found themselves in jail (this was, of course, on the American side in the 30’s).

[This strange final comment was meant to defer suspicion lest officials came to read my notes. Egypt was effectively a police state. “Strawblow’ was Sadat, “Durante” was Nasser. The words in parentheses were just rubbish.]

The revolution in Egypt stripped Serafim of his wealth, and his true worth is now demonstrated by the ease and dignity with which he assumes his position behind the desk of the Golden Hotel, one of the properties that remains in the family. Land and cash were nationalised. Buildings were merely heavily taxed.

His reflection on the Aswan Dam, on the need to mechanise farming, on the ability of Arab culture to survive the machine age (he says it will – I, as usual, remain pessimistic.)

Menu at Riche [a local restaurant]:

Dorma (stuffed cabbage & marrow) 18 piastres

Awa (Zeiad, Marbut) 4 ½ piastres

Soup/spaghetti 5 piastres

[One piastre was worth one British penny, or 2.5 cents US]

Robes are called Galabeia in Egypt, Shuka in Turkey, Djellaba in Morocco/ Algiers.

Walking on the crowded catwalk across Tahir Square in Cairo I noticed that though the crush looked impenetrable, when you walked in it there was always space allowed you – provided that you didn’t move at your own pace.

[Tahir Square was a huge intersection in Cairo. To enable pedestrians to cross it an equally huge catwalk crossed over it. Thousands of poor Egyptian workers, all dressed alike in blue galabeias, crowded over it.]

Cairo is the first city (I presume I shall see others) in which fate as much as mortar seems to fix the fabric. In Tunis the poorest seemed to have some sense of social movement, could dream and hustle a bit. Perhaps it’s so here, but the impression is different. Cairo is intensely populated. 6 million in a relatively small space. Many of these (I don’t know how many) are newly arrived from the farms and are as completely uneducated and unskilled in city ways as can be. It is they who root the city in its ways.

In Cairo I can fill my stomach twice a day for ten British pence, and this is in the heart of Cairo and going no further than 100 yards from the hotel. At the same distance is a cake and coffee house [Groppi’s] where a light breakfast of eggs, coffee, toast and marmalade involves the waiter in bringing eleven separate items – a glass of water, a glass containing cutlery and napkins, two heavy hotel silver jugs of coffee and hot milk, a cup and saucer, plate of toast, slab of white butter, a silver pot of marmalade, another of sugar, salt and pepper, and the eggs. The cup comes from the kitchen full of boiling water which is poured out at the last minute. It takes the waiter an appreciable time to unload the tray. The price is 28 pence, about the most a citizen of Cairo could be asked to pay anywhere in the city.

Anyone living here within grasp of Western standards is plainly able to enjoy the best that the city can offer, while the poorest are able to subsist on the crumbs he sprinkles in his wake – a penny for guarding his car, two pence for polishing his shoes, a penny for simply being somewhere regularly on the off-chance of a service to perform, and so on. There is little evidence of resentment on the one side, or contempt on the other. Once the donor has evolved his routine, and his small area of patronage becomes familiar, the relationship is warm and benevolent on both sides.

This mutual respect is fostered by the clear duty imposed on the Moslem by his religion to donate a distinct fraction of his wealth or income to others in need (I think 10%) The other duties are: to pray five times a day, to keep himself clean – particularly the ‘private parts,’ to do to others as he would be done by, and to visit Mecca once (if he can afford it). The stability of this system depends on a general belief that it is right, good and practicable. Morale and morality go hand in hand. Where external forces seem to strike at the viability of Arab society they are easily seen as a threat to every Arab’s self-respect, without which he cannot be satisfied with his place in society. I am sure that Arab dislike and contempt for Israel is rooted in the view that the Jews, whose ethical system compares so closely to the Arab system, have betrayed themselves and God for personal gain. Israel is perhaps the Trojan horse of the West.

In the aftermath of the ’73 war, Cairo lives in a euphoria of vindication. Egyptians are convinced of a great victory. They have shown the world. Now they can negotiate honorably, and after a few weeks are ready to discuss their mistakes and weaknesses, to begin the process of dismantling their former idols. Other Arab countries who suffered defeat (the Syrians) or who could take no active part in the war (Libya, Saudi Arabia) are less willing to call it off. While Egyptians can joke about Quadaffi fighting to the last Egyptian, the Libyan feeling is that they too want their self-respect established in more dramatic terms. Thus the oil weapon is used not simply for its tactical value, but as a sword for Islam.

It now seems that a negotiated settlement is possible (no more) at considerable inconvenience to the West and given agonising re-appraisals by Israel. Such an outcome, now or later, presumably involves a general recognition that the Arabs are free to go it alone as a society united in its religion and ethical practice and financed by a realistic income from its resources. What then?

Mine is not a political reconnaissance. I have met no members of government, enjoyed no confidences from the wealthy or influential, but I will relate what happened among the people I did meet, experience always being more valuable than promises or advice.

Next week: Up the Nile without a paddle

It’s not too late to reward me for three years of wonderful story-telling with these notebook extracts, you can send me a one-time $100 subscription.

Before we get to the notebooks…

Listen, I know you’ve been enjoying these notes. At various times I’ve asked for feedback, and some of you have been very articulate. I don’t have a very large email list but it’s stayed fairly steady for the three years I’ve been doing this – and of course a lot more people have been reading me through social media.

Now I have to ask myself, why am I doing this? It’s work – quite a lot of work. I justified it originally by the books I was selling through the site, but the truth is you’re not buying them from me any more, probably because you’ve got them already – and I’m grateful for that, of course – but still I feel the need to be acknowledged in a practical way. The plain truth is it costs more to maintain the web site than I get from it in income.

I’ve heard from many of you over the years. I feel I know you. I think some of you would like to contribute, and it’s up to me to give you a way to do that.

Several of you have said you’d like to see the diaries as a book. It’s an interesting challenge – “The Real Motorcycle Diaries” perhaps – but much more difficult than my autobiography and probably more expensive. So here is what I propose (I’m trying to banish the word ”deal” from my vocabulary):

You send me $100 (or your local currency equivalent) to reward me for three years of wonderful story-telling. Let’s call it a One-time Subscription. That seems fair to me. You’ll find the offer on the books page of my web site.

If it all adds up to enough to finance a book, or some other solution, I’ll do my best to make it work. And if you have other ideas about what to do with these diaries, let’s talk about it.

Meanwhile, there’s all of Africa still to look forward to.

FROM MY NOTEBOOKS IN 1973: Alexandria and Cairo

November 14th

My day for sightseeing starts poorly. Showers spill fresh floods across the roads. Visit the tourist office and meet with bovine response from ladies assembled there. To garage first, to find a spanner and manual gone. They give me another spanner, but the manual! So easy to think STOLEN. Still brainwashed by tales of thieving Arabs. But the younger of the men – that charming, soft-spoken best of men who wears the khaki overalls reminds me that I took it to the petrol station to buy oil. Of course! My own stupidity, but on their faces only great relief and pleasure. We march off together in the rain and find not only the manual but the spanner also. Once again virtue triumphs and my Western paranoia put to shame.

Drive to Montasah Palace (King Farouk’s summer house). Fine marble staircase – with rooms arranged in tiers around space open to roof with cheap-looking stained-glass partitions off floors. But light is very good. Otherwise, expensive bad taste. Bathrooms lined with alabaster tiles, but sanitary equipment and design ugly. Foolish trinkets in cabinets. Empty house, empty lives.

Fascinated by the showers. Cage of hot water pipes, showers from above, jets from below. Perfect Edwardian plumbing miracle in that ‘chromed’ metal with dull sheen – was it nickel plating?

Gardens just an ostentatious display of date palms and small firs. Rough lawn. Best of a bad job. Back to hotel for lunch. News of discord between Israel and Egypt disturbs atmosphere. I decide to leave after lunch, rather than stay another night. Aat end of lunch a telegram arrives. It’s for Pacaud. He opens it and takes a sharp breath.

“Mon fils est mort! Je le savais. “ [My son is dead. I knew it.]

His grief is profound and inconsolable. There is a short story to be written about us four at the Normandie. (Mme Mellasse.)

Road to Cairo. Groups of mud houses, dripping hay from the roofs. What are the round cupolas? To collect water? Stables also. Some beautifully made of mud columns, spaced to exclude bigger animals. Huge sails of barges, tall as houses (sixty feet) rising out of the railway line must be road, fill with wind but still require two men pulling. Sail tattered. Many of them stretching out in line ahead. Hard to tell whether there’s room to pass, but must be.

Cairo and the road in blackout. With only my polaroid goggles to protect me from flying sand and diesel soot, it becomes difficult to see where the road is or what’s on it. Bullock carts, donkey carts, cyclists, all unlit, appear on the verge. I catch a lift behind a fast taxi and as an act of faith follow him blindly into Cairo. An hour at 50-55mph. Not comfortable. But Pacaud’s description of route serves me well. Only the one-way systems finally cause difficulty.

Golden Hotel is a bit intimidating at first. The upper floors resemble Alcatraz.

I don’t know now who recommended the Golden Hotel but it was an inspired choice, despite the cockroaches.

Thursday, November 15th

To Reuter Office. Dullforce is middle-aged, lean, grey-haired, unsympathetic. Wife likewise. Brisk, and busy.

Write about arrests. These bureau people are much like the police (in fact all daily newspaper people). Received the minimum of help, much disapproval. It’s the worst kind of arrogance, but I find myself largely immune to the consequences.

Pass on to the Cairo Information Centre, for permission to drive to Aswan.

Eat at Estoril Restaurant in alley off Tallaat Harb. Not very good.

Meet two young girls outside Suez Canal Co. offices. Birds are singing loudly in trees. Animated conversation with men through the bars. Egyptians always good for a laugh. Very warm people. After an attempt at lessons in Arabic, go for an endless walk through ‘garden city’ with Youssef, an accountant with Nile Transport Co. who described himself as “economist.” Earns 35 Egyptian pounds a month. (i.e. £6 a week). In five years’ time he will earn £8 a week. Says he likes the security. Went to East Berlin in Egyptian Youth delegation. Conversation oozing with emotion, empty of content. Leave girls and speed off in a taxi to something resembling an outdoor Peabody Building. Dodging from bloc to block until suddenly, without warning, into small flat bright with several hundred watts and solid with people. I counted over sixty with difficulty. Drums and tambours banging away. Two families celebrating the betrothal of two young people. Immense gaiety, no alcohol, ‘belly dancing’ by men and women (with scarf tied around hips). “Mucho Corazón”

Friday, November 16th

Gizeh pyramids. It’s a general holiday. Pyramids are at the edge of Cairo. West of Nile, on a raised area. A throng of guides, horses and camel drivers make an appreciation of the pyramids impossible. To have first stumbled upon them must have been marvelous but I can find no sense of awe for these lumps of stone. Less barbaric than Teohuacan, but still a monumental egoism. The marvels are all abstract – geometry, astronomy, etc.

I can’t resist the importunities of a guide who is clever enough to be less clamorous than the others, but he shows me very little. In a tent he gives me good tea made on a primus stove by a pretty wife dressed in pink. She boils the water and tea vigorously, decants it, boils it again, decants it again. How the sugar got in or where the tea leaves went I have no idea. Hard upholstered couches on two sides.

Walk away to pyramids. Into second pyramid (Queen Sharfeen?) One tomb with hardboard partitions. Graffiti early 19th Century. G.R.Hill and Scheistenberger etc.

To first pyramid. Meet two unintelligent lads, but girl with them is more aware. Into Cheops. Inside like something out of [the film] Metropolis. All scaffolding and duckboards.

Jack Hulbert was a much-loved actor and comedian in the prewar days – with a big chin and a twinkle in he eye – you can see the resemblance, though how Faris the camel driver knew about him remains a mystery.

Ready to leave when I give way to camel driver, and now my reward. Because he gives me a great ride, over an hour, into the sand dunes, on “Jack Hulbert” [that’s the name of the camel.]

He is bright, humorous, great fun. We take a roll of pictures. Him and his mate.

But what in God’s name does the average package tourist get out of it all?

I really rode that camel, rein, switch and heel. My thighs were aching from the unaccustomed movement. JH lurched and swayed and hobbled along, with brief bursts of crazy trotting. I crossed my legs, Arab style, over his shoulders. He is six and will go on probably until he’s twenty-five or so. Sacks of ‘clover ‘at his side under heavy embroidered cloth. Take two sets of pix. First roll failed to attach to spool. Drivers called Faris Hamse (No. 62) Mandor Shahat (77).

I’m disturbed by my failure to respond to the pyramids and question the quality of response in others. I know perfectly well that if I want I can whip up a storm of fancies and imaginings but I was determined to let the pyramids do the work. As props for a mind hungry for sensation they do very well, no doubt, but as objects to inspire pure awe or wonder I think they fail. Man has demeaned them in scale and industry. Rockets can be built taller than Cheops, more intricate, by more people, and sent to the moon. They have been surrounded by bric-a-brac, haggling, and petty detail.

I’ve been told that it’s better to see them first at night, through ‘son et lumière’ and that it’s a very good show. I quite believe it, but that’s a different matter. With sufficient skill at my command I believe it would be possible to illuminate the history of mankind by “son et lumière” in my kitchen.

The pyramids have an absolute virtue, but depend, like all other earthly things, on perspective. When the perspective is altered, whether by a persistent camel driver or a new catch-penny museum built up against the face of the pyramid itself, the pyramids fail and it is up to the individual to supply, by an act of imagination, what has been stolen. I refuse, because I feel I will become an accomplice of the despoilers.

[I seem to have gone through a rather arrogant phase. Perhaps it was the only way I could find to deal with such a short exposure to such an extraordinary phenomenon.]

If you’d like to reward me for three years of wonderful story-telling with these notebook extracts, you can send me a one-time $100 subscription.