Articles published in January, 2026

The five hundred or so miles from Gedaref to Gondar were the toughest five days of my entire journey – in part because I was still new to the game. When I returned 28 years later it was virtually unchanged. Then the Chinese came. Today, I’m told, it is paved.

December 17th

By the fourth day I was ready to contemplate the possibility that this journey will never end and to face each problem as part of my life. This is my life and I am surviving it. What else matters? So on the fifth day as I leave the camp I almost immediately find myself climbing steeply against an avalanche of loose boulders to the top of a peak, only to find that a box fell off at the bottom.

Park the bike and walk back down, contemplate the loss of what? Can’t even remember which box is lost, what’s gone? The cameras? Every potential or actual disaster finds me more philosophical. Hear distant voices and engine. Some people have found the box. What are they doing with it? What a way to put Ethiopian honesty to the test! A little further down meet the truck coming up. They are enormous lorries, climbing so slowly, loaded with sacks of grain or cotton. It stops. The driver points to his left. I assume he means he has seen the box. No, he has it there in the cab. I climb in, with helmet and goggles and ride back up to the bike. It is the box with food, torch, washbag, etc.

I am offloaded and settle down to repairing the damage. Bolt torn though the fibreglass. Botch it up with wire. Groups of young men come and admire – and return with a blackened kettle full of cold, clear water for me to drink.

So I set off again. Today the climb is intense. Up and down, and further up and down, and still further up. Always there is a mountain ahead. Loose rocks a constant challenge. Watching the road every minute. Eventually I go over again, sprawling across the middle of the road. Bike flat and my heel jammed under the left-hand box. What’s holding it there? The strap of the boot – there ”for when you come off.”

[Back in London when I was buying kit for the journey, the only items available were a helmet, goggles, a plastic tank bag, gloves and boots. The boots were very simple, but there was a strap and buckle across the arch which seemed to serve no purpose. I asked the kid serving me what it was for, and he said “It’s for when you come off” which made no sense at all. Now it was caught on the axle, trapping my foot under the wheel.]

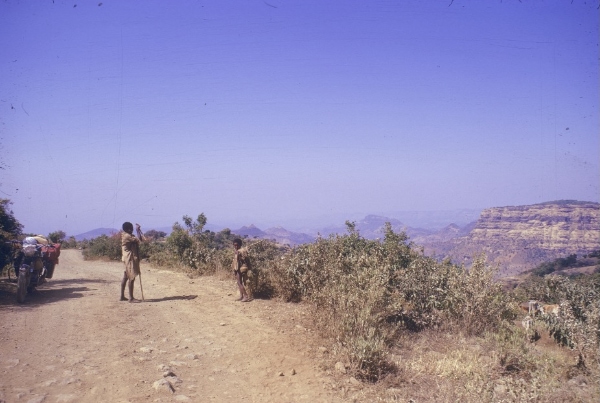

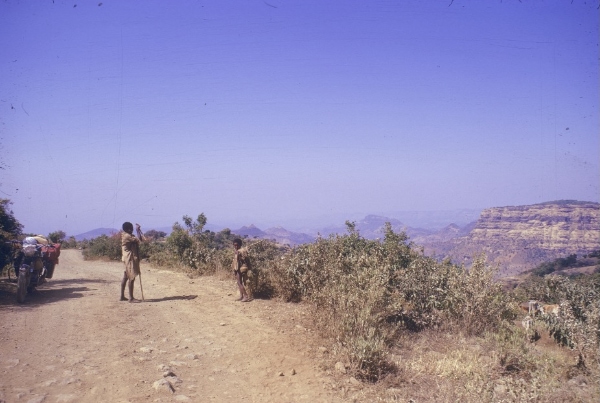

My goggles have gone. I think they must be in the lorry, which has passed me just as I got the bike upright again. I have found a technique for lifting the bike now, by twisting the handlebar, but with my wrenched left arm it’s a big struggle. Drive on. Bike all the better for a rest. Now country changing radically. Many shrubs, green and red, grassy banks and slopes, with boys popping out naked but for a rag over their shoulders. Alpine country – 18th century Switzerland.

Stop for a rest. Boy of 14 or so pops up through hedge. And holds out his flute. Bamboo tube with holes and binding for mouthpiece. Can make nothing of it and ask him to play. He produces a thrilling and intricate music seeming to play on two registers simultaneously. With embellishments round a simple melody. Lightning finger work.

[I was so wrapped up in my own ordeal that I entirely failed to appreciate the situation. Probably he wanted to sell the flute. The music he played was astonishing – a virtuoso. I left without offering him anything in return. It hurt me later to recall it. A little further along, around midday, I came to a village.]

Chelga (now known as Aykel)

At lunch time. Village confirms Alpine sense. The way groups of people stand around. Less spontaneous excitement. People contained, though curious.

Find restaurant. Quiet. Six men at table. In suits, some with overcoats on. Dark clothes. Conferring discreetly. Much fuss made of them. Their faces shrewd, cunning in European way, but black. Exude power, influence. Mafia?

One of them instructs owner to get my passport. Examining it nonchalantly, with neighbours looking casually, then passes it back. No direct contact except smiles in my direction. Eventually they leave. Behind me, teacher who has kept silent, starts talking to me. The one who looked at my passport is police “general” he says.

He talks bitterly of regime, overthrow etc. Compares Ethiopia to France before revolution. Says I should talk to students in Addis. Warns of bad people on the road who will try to stop me. If I “joke” with them they will steal from me. I must “keep a good face. Don’t walk around Gondar alone.

“But you will have your own trick,” he says.

[I arrived in Ethiopia in the last years of Hailie Selassie’s reign, when it had become an oppressive state.]

On to Gondar. One more ford successfully crossed. Then came off again. The other box ripped away. Repair it with crowd looking on. No hostility. The “improved” road from Chelga is flatter but covered in loose stone. Just as hard. When I finally get on to main road, asphalt, it’s like flying. Feel very good. Triumphant. Deserving. Have all sorts of treats in mind for myself. Luxury hotel with beer, bath and good food.

Schoolboy directs me to Fusil Hotel. Room is $4Eth. Italian hotel. When I get there, boy is there too. Can’t bring myself to send him off but his company is cloying. He wants to please. When I suggest he’s expecting something from me he protests. But in the end, though he helps wash the bike and so on I refuse to give him anything. He gets $10 a month from an American who passed through one day – a Bill Rollafson, a chemist from California. Boy’s father is a priest.

Everything costs more here, and people come up for money. In the road there are some boys who throw stones, some men who look as though they might let go with their sticks. After Sudan the atmosphere is very troubled.

[I rode south to Addis Ababa where some friends, Alan and Bridget, were living. He was there on some UK Government mission. They had invited me to spend Christmas with them. We visited Lake Hawassa, south of Addis, famous among birdwatchers. Then I rode on south towards Kenya.]

A saddle back crane at Lake Hawassa, or so they told me. Not a great picture but it proves I was there.

I wake up every morning wondering what fresh outrage Trump has invoked. Like George Bush, he has looked into Putin’s eyes and presumably drawn inspiration from his soul. I shiver at the thought of what message those basilisk eyes project. Terrorise your own people, go out and bomb something, bask in admiration and gather up your trophies. A peace prize perhaps, a chunk of Palestine real estate. My life has turned full circle. It began in the shadow of Hitler. Will it really end in the shadow of Trump? What a farce.

From the desert to the mountains.

Those days crossing the desert in Sudan were among the most influential of my life, an apotheosis. After my abject performance on that first day, running out of fuel and water and burying myself in sand, the schoolteachers of Kinedra lifted me up and made a hero of me, and from that day on I was treated with the utmost generosity and respect.

My interlude at the tea house among tribesmen of various kinds simply reinforced my admiration. Like every westerner I had heard no end of stories about Arab deviousness and thievery. I took the accounts of their nobility by Lawrence, Thesiger and others with a pinch of salt. Now I had to concede that in their own element they were splendid. The simplicity and respect in our communication was balm for the soul.

Of course, it bothered me that I never caught even a glimpse of the headmaster’s wife. A world in which women were invisible would quickly become intolerable to me, but I was passing through their world and had to accept their customs. The fact that the Bescharyin were all huddled together in the same truck bed, men, women, chlldren, and a foreigner, was proof that custom can give way to necessity. As I was to learn during the following years, it is custom that rules the roost everywhere, however much it is attributed to religious belief or idealism. Arbitrary custom cements society, and it can only be broken by often painful necessity.

Look to Iran for grim proof, if it is needed.

Now the journey continues…

December 13th 1973

From Kassala. Along the railway line. Cracked dry mud. Much of it corrugated. Seemed bad at the time except for some flat stretches where a secondary track close to the line could be used. Before Kash’m-El Girbar, bridge and switchback road.

At a tea-house in Kashm-el Girbar I emulated this man and ate a large piece of delicious Nile Perch, while other customers gathered round my bike. “How quick? How fast?” they demanded. When I was ready to leave, someone had already paid my bill.

From K.G itself I was promised “queiss” track. It was terrible – true washboard all the way. Slept with camels 15km from Gedaref.

[In fact, I spread a sheet on the ground a little way from the track and slept on it, to be woken in the middle of the night by a small caravan of camels travelling over me. I looked up at their huge bodies as they daintily avoided stepping on me.]

December 14th

Next day crowds in Gedaref were oppressive. Left straightaway and found road now worse than ever. Some washboard, but mostly deep ruts – one or two feet, leg-breaking and bike-throwing.

Always having to choose a rut only to find it narrowing, unable to get out. Dropped bike three times, one very difficult– have picture.

So to Doka. Night with police.

[Someone had told me there was a police post on the road to the Ethiopian border town, Metema, and they could be trusted, so I slept on the ground inside their compound.]

December 15th

On to Metema, same road, plus rocks, dips etc.

Went to “best hotel in Metema.” Last night. Corrugated iron roof, rough plaster walls on wooden uprights, earth floor, bar with shelves of drink, owner at small table, upholstered chairs and sofa round another table. First upholstery seen since Egypt. Woman shakes my hand and it comes as a shock to me. I have forgotten about women in public – it’s over two months. At first the impression is charming. Dresses of cotton, knee length – a bit dirndlish. They smile, laugh, suggest that life is a light matter, but in the morning it’s less pretty.

December 16th

Morning in Ethiopia. Camel with small flock of birds on its back. Brillian red beaks, grey and white plumage. Another camel with two men sitting back to back, the rear passenger in bright red blanket (Peruvian?) Both smiling. Huts round, of brick, with conical straw roofs, some tied at top. “Hotels” and “bars”. – women with inviting smiles. The women nursing their illegitimate children and their tightly rolled wads of Ethiopian dollars. Later I notice that it’s the girls who are first to stretch out their hands, and it seems that in this country the women take onto themselves the stigma of sin, avarice and corruption. Leaving the men to enjoy a lofty nobility. It may become clearer but one thing is already clear. The relationships between the sexes, however they are customarily managed in different countries, produce rich and extraordinary phenomena.

I was overjoyed to arrive in Metema yesterday, because it marked a solid step forward. Today it rather disgusts me. I can think of no reason why anyone should want to be here except to cash in somehow. Is it a typical border town? Evey hut is a ‘bar.’ Every building bigger than a hut is automatically a “hotel,” with a rectangle of painted metal slung over the door to say so (usually blue or red).

Dawn breaks outside Metema

The customs say I must wait until 3pm. Thought overwhelms me with horror; The travelling is so hard I have to keep moving, just to keep up some sense of achievement to balance the hardship. I listen to a policeman who says I can do customs in Gondar and set off into Ethiopia.

Had a glass of something by mistake when I asked for bread. Yellow tea, with a familiar taste that I couldn’t place and didn’t much care for. (Although it was faintly reminiscent of Bovril.)

Following day, Metema to Gondar. Road vastly improved. i.e. like a normal cart track. Then fords – 1 and 2, terrifying – 3,4,5. Then very steep climbs, very hot. Bike stalls halfway up. Have to carry stuff to the top.

Sometimes the rock is black, sometimes pink which powders into dust. The light wipes out all contours when it hits the dust – can see nothing but a sheet of glowing pink and white. The improvement in the road was illusory. In its own way it was as bad as any. Steep rising and falling road, loose rocks, desperate dashes into fords and up the steep exits, overheating until engine fails. Twice on the ground within a minute. Near exhaustion at times. Back jolting is painful, left arm constantly wrenched when wheel spins on a stone.

Last big ford of the day is too much. Some men gathered to help and suggest I sleep there. They are building a bridge. I am about halfway between two main villages, have come about 100kms. Wash feet, body, socks in river. Drink some. Have tea with road gang; eat half tin of Sudan mackerel. Lie in bed listening to men talking round their fires. One man has voice that dominates with amazing range of expression. All the men, it seems, have two voices – a normal speaking voice and one that jests and mimics and plays on a higher register with very rapid, light consonants and cat-like vowels.

December 17th

Road continues. Leave the bridge builders early. This is the fifth day of my ride from Kassala. Every day the road has seemed just short of impossible _ and each day new difficulties.

[That night I recapitulated in my notebook what had happened in the last few days.]

I am feeling now as if I am being put to a series of ingeniously graded tests. First outside Kassala, the dust mud, cracked and ridged. – carburetor stuck at K.G. Then, after tea when the good road was promised, the washboard for seventy miles, a rattling and shaking that should have torn the machine apart. No relief – if anything becoming more severe. – until the sun moved into my eyes as the road swings to the south west and I dared not go on. Slept on the camel track. Next day washboard continues to Gedaref where I eat fish, drink tea, and get stared at, and escape on the road to Doka. Now the road is both washboard and rut. Sometimes the ruts are two feet deep and hardly that wide and one must ride through them with boots raised for fear of breaking legs against sides. Where the ruts are less serious the washboard becomes correspondingly more severe.

In Gedaref police station (why did I go there? Heaven knows) I met an African refugee from Rhodesia. He said the police at Doka were nice, so when I get to Doka after seven or eight hours driving, I accept the chance to stop honourably. From Doka next day, to all the other hazards are added steep inclines covered in loose rocks. It’s important to remember that these are not consistent hazards. Anything can happen at any moment. It is dangerous to take one’s eye off the road for an instant. I have gone over twice now, not through lack of attention but through taking the wrong line and being caught in converging ruts or in a bad bit of rock. So I am ready for anything and still dreading it. Even inventing impossible hazards for myself, only to see them realised. The impossible ford, the rocky path along a ravine, etc.

Why no puncture? Why don’t the tyres tear to shreds? I think that might finish me. I am full of admiration for the bike and tyres. Why doesn’t the Triumph just die? It has no need to go on, unlike me. It protests, chatters, faints, but always resumes its work like a faithful donkey. What havoc is being wrought inside those cylinders?

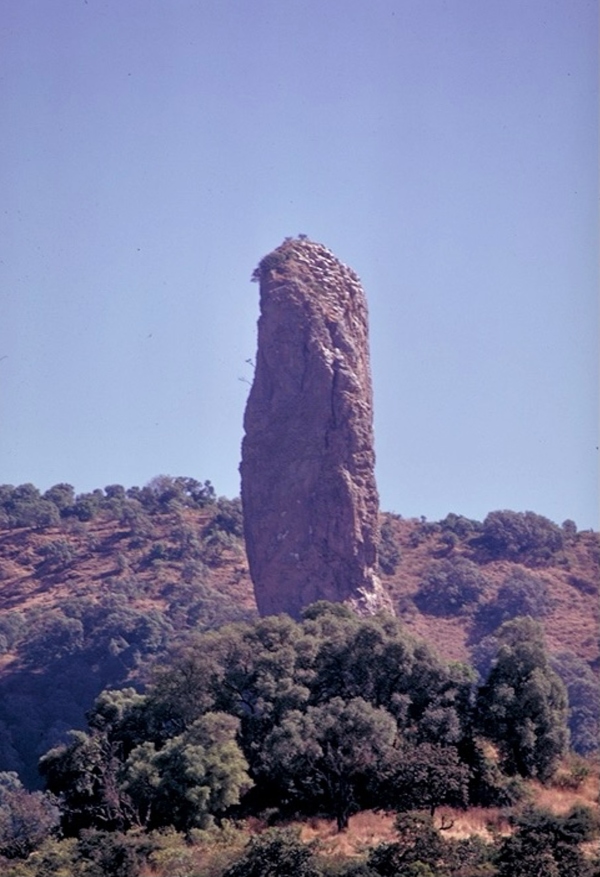

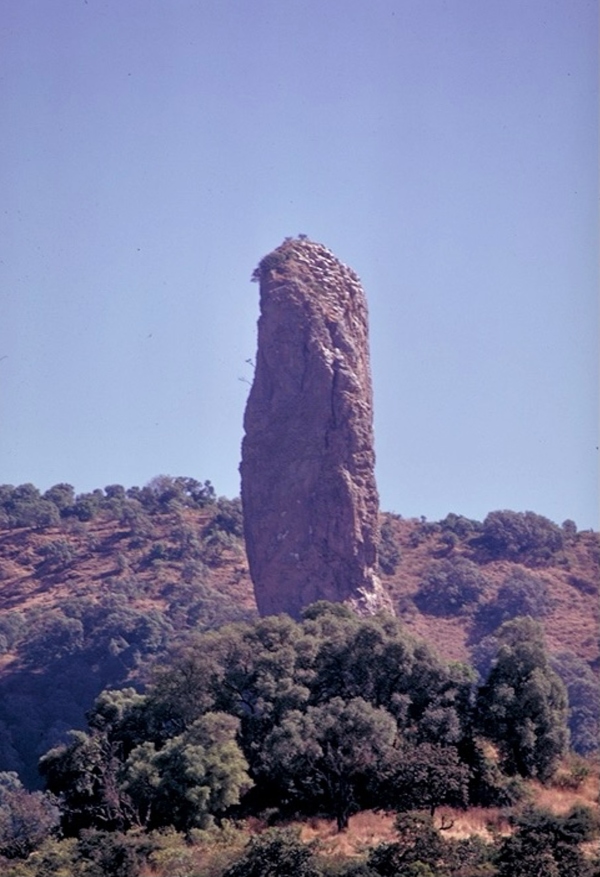

On the third day I passed this extraordinary pillar of rock. I saw it again, unremarked, when I went past 28 years later. I wonder if it’s been given a name yet.

It’s becoming more and more difficult to do “business as usual.” A lot of people ordered books from me before Christmas, and it was a little while before I discovered that Trump’s tariffs had thrown a spanner in the works, and all the books I sent to the USA began coming back to me.

I’ve refunded the majority of those who ordered them. The postage, which came to roughly 300 euros, is lost, of course. Fortunately, many of you responded to my “Subscription Offer” so I am certainly not complaining. I can’t resell the books because their all dedicated, but I’ll keep them, so if any of you happen to be passing by in the next year or two, you can drop in and pick yours up.

Cheers, Ted.

After two more days as a guest of the boys’ school in Kinedra the teachers finally gave me permission (because that’s what it felt like) to continue my journey. I was confided to the care of a government official on his way to Kassala, 200 miles away, from the neighbouring village, Sedon.

Wednesday, December 12th

From Kinedra in morning. Thermos flask of tea prepared. Headmaster’s wife has fed me throughout. Drive to Sedon. There is a Land Rover going to Kassala. Forest District Officer, Mohi el Din, needs brake fluid.

Mochi el Din, in the yellow shirt, asked me to follow his vehicle, but they drove too fast for me. They stopped until I caught up with them. I said I would go on alone. He told me of a tea house halfway to Kassala called Khor-el-fil (Crocodile’s Mouth)

Along the way I passed cattle travelling through a mirage.

I found the teahouse without difficulty, and spent some peaceful hours with tribesmen playing primitive music.

A home-made harp made with a wash basin.

A truck arrived and I wandered over to meet them, members of a tribe called Bescharyin.

When I told them I was going to Kassala they said the sand would be too soft and I should load the bike on the truck and travel with them.

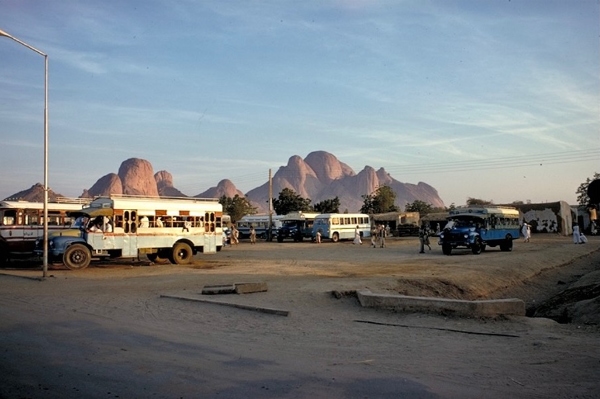

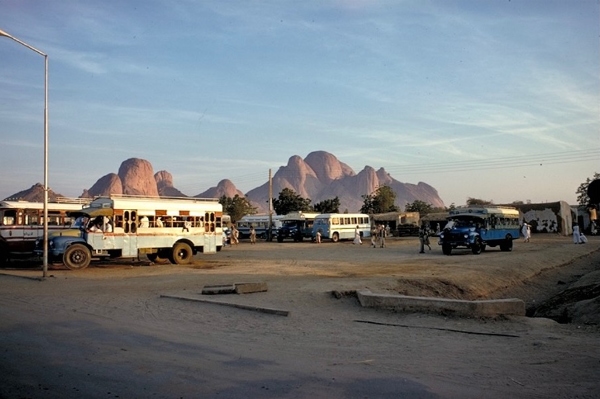

Before we arrived one family got out. Behind them are the amazing mountains of Kassala.

In Kassala, Hotel Africa – 30 piastres a night for bed in room for 6. Slept on balcony. Tea boy had holes in feet. Wanted treatment. Gave him Septrin and stuff, through Egyptian teacher of chemistry. He gave me free tea.

After Kassala the route continued south-east past the huge Kashm El Girba dam to the Ethiopian frontier.

On December 5th the ferry from Aswan came ashore at Wadi Halfa or, more correctly, at a ramshackle assemblage still growing to replace the town, which now lay below the waters of the lake. I had hoped to get back on the bike but was refused permission and petrol, so I had to take the train.

My Dutch friend (hatless) dealing with his luggage. My bike was already in the wagon.

With the Dutch couple I had befriended, I travelled to Atbara, where apparently there was only one hotel. They took a taxi and I followed on the bike.

THE hotel. The rooms at the back were cubicles looking out over a verandah on to a courtyard.

December 6th

Atbara: Hotel courtyard. Pale green lime-wash. Green oil paint. Entered to be greeted by five Arabs with sherry and marijuana. A joint pushed straight into my hand. Played some music but they weren’t interested. Interest centered more on Anthony. Why not? He was suspicious, I think. Later, the southern Sudanese, Fabiano, said the chief Arab was a thief who pretended to be drunk to get others drunk. Used the word ‘teep’ but all his p’s are f’s and his f’s are p’s. i.e. pipty and fresident and feople, etc. We got into quasi conspiracy about Sudan’s internal problems and the Eritreans, but my own astounding ignorance left me unaware that the Eritreans were Moslems opposed to Selassie’s Christian regime, and the southern Sudanese, being Christian, are naturally opposed to the Eritreans. I had imagined it the other way round i.e. underdogs supporting each other. Naïve innocence.

Saturday, December 7th

Bent foot brake [lever] back into place by dropping bike on it. Cleaned Oil Filter. Distilled water – to be found. Tightened nuts and bolts. Some movement on barrel nuts. Tappets? Not yet. Chain tensions; primary all right. Rear chain loosened two turns.

In Atbara we met Thomas Taban Duku and then Fabiano Munduk. Both African Christians from the south of Sudan.

With Fabiano, an evening that started when he came to the hotel with his nephew Peter, a four-year-old boy in brightly striped jersey tunic and shorts. They had come from school sports day. All day I had heard martial music of the Empire drifting across. He explained they had been playing musical chairs. We drank two bottles of sherry between us in a bar, then took him by taxi to his brother’s house. Brother is in police (a captain, he said). Saw one room, open to yard, all in brown and over brick. Brother’s wife spoke no English. He got her to give small bottle of home distilled date liquor. (Like eau de vie)

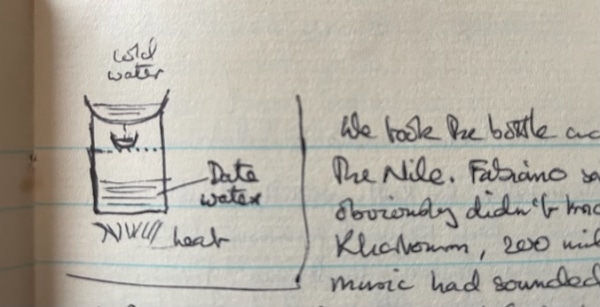

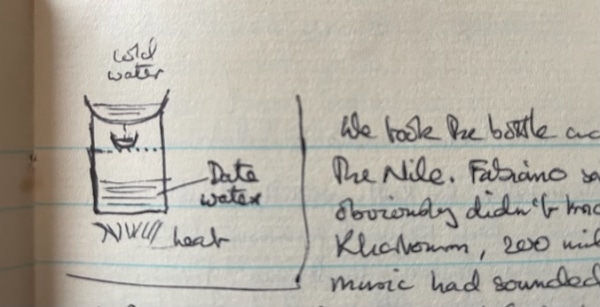

Dates left in water for seven days, then container put over fire. Above it a lid perforated. On that a small bowl. Above it a bigger bowl as a lid and condenser, filled with cold water.

We took the bottle and walked across cultivated ground to look at the Nile. Fabiano said the White Nile was a day’s walk away. He obviously didn’t know the Blue Nile only joins the White Nile at Khartoum, 200 miles further south. We walked back to place where music had sounded. Fabian was dodging about looking into bushes, in the manner of Don Genero looking for cars.

[Carlos Castaneda, a popular writer at this time, described his apprenticeship in shamanism in The Teachings of Don Juan and other books.]

I think he was looking for animals or snakes. We had been hearing about his life in the bush – ‘bus’ – when he and his brothers were refugees from Sudan after his parents had been killed – he said – by the Moslem army of the time. He is proud of his brothers. They are twelve. Two are at Oxford, one doing economics, another librarianship, the others are mostly in the army – all officers He is the youngest and least qualified.

The music came from a wedding party in a community on the edge of Atbara. Large square clearing with canvas spread over large area, illuminated by bulbs strung out in a large rectangle. Rows of chairs all round. Many children jostling for good position, scrapping with each other, but although they pushed each other around quite hard there was no bitterness in their manner, and no crying. Fabiano says the children are allowed to be independent but this only works of course in a simple environment with large family structures.

The band arrived in an army truck. We were given favoured seats, and then plates of food were brought specially for us. Tarmeia, bits of meat, salad, sweet pastry, bread and water. Water in gilded aluminium bowls. When music started men would wander over casually, sometimes two together jigging to the beat, snapping the fingers of one outstretched arm, to indicate their pleasure, and reach over to touch one or more of the players. Then they would retire again just walking away slowly.

[Account of Atbara to Kassala in letter home.]

Monday 10th

[The whole of the following week’s experience is described in detail in Jupiter’s Travels.]

Left Atbara. Tried to find way from town. Took an hour. [Everyone said “the road to Kassala is queiss” – meaning good. But there was no road.]

The road to Kassala.

After three hours, in sand up to axles. No water. Too little petrol. Acid in bottle. No money. Come to Kinedra. School. Welcomed. Fed. Refused permission to leave. Headmaster said, must get more benzene first. From car? But car had none. From District Officer at Sedon. But he had none. By lorry from Atbara. But lorry broken down. By lorry next morning. But no lorry.

[After two days at the school I learned there was a bus back to Atbara. I was introduced to a merchant who was also taking the bus and with my five-gallon jerrycan I accompanied him to Sedon where the bus stopped in the night. He spoke no English at all. We lay on the sand in the smpty square to wait.]

“Sudan seňora queiss? You Sudan seňora? Sudan seňor queiss? You Sudan seňor?” Insistent, quiet, gentle. Just teeth in deep shadow framed by turban. Light touches between legs. Seductive, compelling, out of any moral context. Could imagine it.

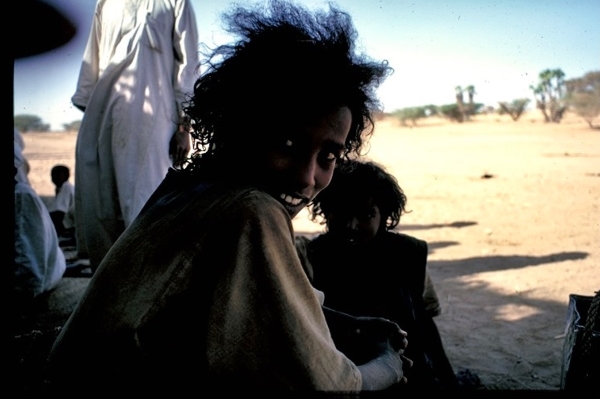

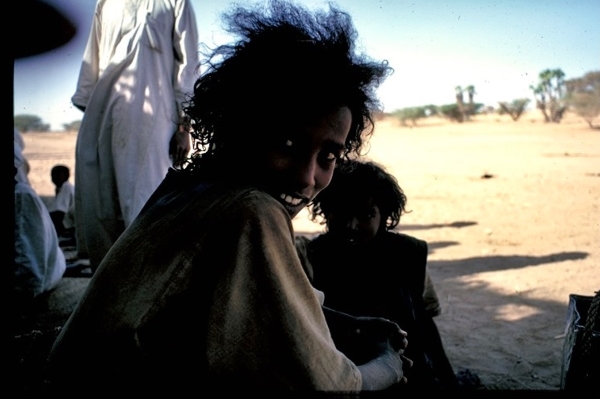

At last, there was a bus. Bus arrived at 11.30pm. Ford chassis. Heavy riveted steel body built in Khartoum. Out tumbled horde of people. Many with swords. Scabbards shaped like paddles. Crucifix grips. They are a tribe called Bescharyin. From Sedon until Goz Regeb. Most are nomads. Their hair is long and the strands are glued together with oil, called oudak – animal grease, and wear an ornamental curved stick used as a comb, sticking out like an Indian feather, but horizontally. They wear a waistcoat, galabeia, and trousers with crutch below the knees and tied by cord. Three-tiered clothing. All fell to the ground and slept until 4am. I was happy to sleep too, but it got cold and I had no cover. At 4am the bus left for Atbara. Very bumpy. Much coughing. A sort of stale, damp smell. Two B in front of me, hair dangling before my eyes. No expression. Very stern. After dawn people began getting off. Outside Atbara, my companion, the merchant, vanished mysteriously [while I slept.] A family of B’s descended, a pathetic huddle of humanity set down on the sand, with their bundles of mats, sticks, pots and bags, still cold, kids bare chested. They appeared momentarily unable to cope at all.

In Atbara looked for Fabiano to recover cutting, and lost others in the process. Southern tailor’s shop had African flavour. Clear distinction between Arabs and Africans – each considers itself the elite. Tailors rather condescending about clothes they are making. Material from China, Egypt inferior. Suit costs £2.50 up. Got lorry back to Kinedra. Took road in a wide sweep across desert – the road I missed (or dared not find.) which would have got me here faster.

Lorry stopped about a kilometre from Kinedra. I started humping my jerry can across the sand but was soon met by a boy with a donkey, who relieved me of my burden immediately.

I had intended to go to Sedon to photograph the water pumps, but the teachers of Kinedra would not let me leave. They insisted I accompany them to the river bank to take pictures. Waded in the river. They said prayers. Each had orange-sized patch of sand on forehead. Then visits to the village shops, and the home of . . . . . . brother who has refrigerator. Little bags of flavoured ice. Shabby furniture, not worthy of Austin’s [a popular London warehouse of used furniture.]

[I was persuaded to stay two more days at the school.]

Goodbye, until next week.

PS: Like most people I come into this New Year with grave premonitions. I see absolutely no prospect of Putin stopping the war. Trump’s involvement is toxic. Europe must pull itself together. What can I do about it? What can AI do about it? Watch this empty space.