From My Notebooks In 1973: A Missing Chapter from Palermo to Tunis

9th November 2025 |

A missing chapter. For those of you bothering to follow this series of notes chronologically I have to confess that I mistakenly left out a section of notes about the ferry from Palermo to Tunis. Because I think it was significant and reads rather well, I’m going to interrupt the story and tell it here:

On the ship between Palermo and Tunis, the second class lounge was dominated by two personalities: the Italian barman and an itinerant Tunisian visiting home from the great casual labour markets of Northern Europe. They were at opposite poles of human conduct.

The boat left at 9.30 – a fine looking, modern boat, with drive on facilities, called “Pascoli.” On the deck I met, briefly, two somewhat effete Englishmen with a Renault, driving back to their home in Tangier. I still seemed a long way from the kind of Africa I was expecting. Then I saw the Tunisian Hassen from the market yesterday, and with him was the man who became the pivot of the ship’s life for most of the morning.

He was chubby, Castro-bearded in a green tunic (US style). Shock of black hair at the top, pale skin wrinkled by much facial work. Coconut shaped head. About 30 years old. Started by being merely noisy.

“Ah you, vous, wass machen, sprechen Deutsch. Ich auch. Scheisse.” Burst of Arabic. “Ich bin Hamburg. . . . “ and so on. Then he started singing. I just thought he was a disagreeable oaf, and went down to the lounge for a beer, where the Italian barman held sway. He represented all that was petty and corrupt. He treated the lounge and its occupants, mostly Tunisian Arabs, as his private colony. His strutting and posturing were unforgettable. The bar was his seat of administration where he granted or withheld service as capriciously as any despot. No, withheld is too mild. Refused, volubly, rudely, with accompanying gestures. Every now and again he would fly into a tantrum about the television set tuned, naturally enough, to a Tunisian program and insist on switching to an Italian football match, although the picture was scarcely visible, the sound was no more than a roar of static, and he himself never once looked at the screen. When his bumptious little body, with its prematurely pregnant belly slung over the Italian sailor’s sash, came round on a tour of inspection, passengers dozing iin their seats with outstretched legs had their feet roughly kicked out of the way, while his equally offensive sport was to fling empty bottles into a large container where they fell with a regular shattering crash. It was truly breath-taking to see one man seize upon his environment which theoretically belonged not to him but his customers, and make of it an instrument for the complete expression of his selfish nature while the rest of us submitted in our various ways, resigned, resentful, or merely numbed.

He represented in my eyes all that is brutal, greedy and corrupt in human behavior, and he was a powerful influence in stimulating my sympathy for the Arabs. Short of violence it was obvious that the man could not be stopped.

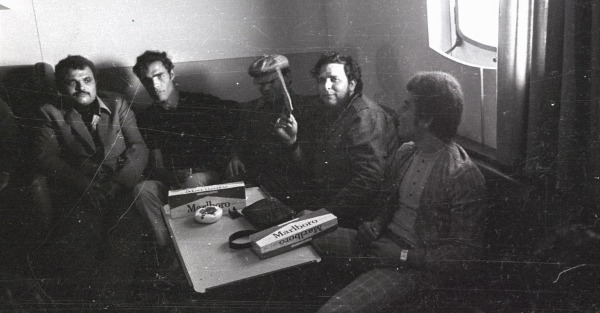

The poet is waving a paper in front of Mohamed’s face

The singing buffoon came in a little later, when it started to rain outside. He sat at the far end of the lounge still chanting and smiling as though at some Sufi vision. In the confined space the songs were much clearer. Hassen said they were nonsense about girls and love, and he was apparently making them up as he went, but at least he offered an alternative kind of vitality to the terrible malignant power of the barman.

The Arabs nearest him began tapping and clapping along, and others drifted closer, but he continued for a while as though he were unaware of any of us, playing the fool for another audience that only he could see. The barman was noticeably annoyed and the tempo of his outrages increased, but although he still commanded two thirds of the saloon he did not meddle with the singer, whose territory was growing. I sat for a while on the border line of their two spheres of influence, and it was like looking out on two different worlds. To my left, shouting, hostility, the smashing of bottles and, from the TV, the gibbering howl of the ether. To my right, singing, laughter and a beat that was beginning to reach into me. Hassen and I moved across to the right.

The singer judged this the moment to come out of his private retreat and began to respond to his followers. I could not imagine how I had ever thought him distasteful. At worst he was a simple clown, but his power now seemed to grow as the barman’s dwindled. He interrupted his buffoonery with poetry, and Hassen told me it was original and good. The same thumb and forefinger placed the words in the air with a precision and meaning that I felt I could understand, though I spoke no Arabic. The songs also became longer, more lyrical. Slowly, over a period of several hours, the pitch of his performance built up. The barman by now was utterly effaced, the TV could no longer be heard. Everyone in the saloon was with the singer, his to a man, and yet he still seemed strangely detached from us, not feeding at all on our adulation in the manner of a Western “star.” Nor was there ever an attempt by anyone to compete with him. He remained the focus of energy for the rest of the crossing.

Towards the end he moved from songs and poetry to oratory. It was a long speech, and if the rhythms were anything to go by, it was in the Arab equivalent of blank verse. His voice now was very muscular and gritty. The harsh, hard-nosed syllables flew out in formation and beat on my ear. His audience replied with moans and cries of agreement. I imagined the voice amplified a thousand times, a hundred thousand times, from loudspeakers on all the minarets of Islam.

The sounds conjured up an atmosphere of great ferocity, yet the sense of the speech, it turned out, was moderate. It had to do with peace and war in the Middle East. It praised the moderate statesmanship of Bourguiba, and poured scorn on the troublemakers who would fight, like Qaddafi of Libya, to the last Egyptian. Hassen said it was good sense, realistic and very poetic.

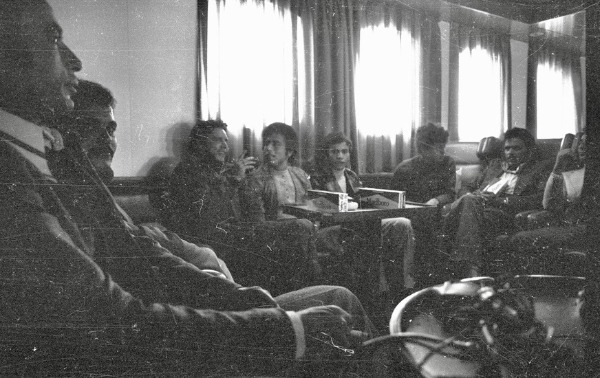

The train driver from Sousse translated and gave his view.

“At first I thought he was a fool. But now what he says is really impressive. It is realistic and good sense and very poetic.”

It was well after dark when the ship arrived in Tunis. By then I had made another friend, Mohamad, a young Tunisian who was one of the singer’s most enthusiastic accompanists. He was more stylishly dressed than most, with a jazzy peaked cap on, which he never removed. His nickname, loosely translated from Arabic, meant “The Swell.” He asked me where I was going to stay in Tunis, and I said I had no idea.

“Then you will stay with me. My family will be very honored. You will have everything we can offer. We will be extremely proud to have such a famous man in our house and our friendship will last forever. I have a dark skin but my soul is white as a lily. You will be safe and well in my house.”

Before leaving the ship I happened to notice the barman. He seemed a rather insignificant person, cleaning up after us, hardly worth bothering with.

The poet is in the middle. Well, I never claimed to be a photographer.