From My Notebooks In 1973: Aswan and Lake Nasser

21st December 2025 |

Thank You Very Much

First of all, I want to acknowledge the response to my offer of a One-time Subscription. It has released a small flood of generosity which makes it plain that over time I have established a place in many lives. Not just through this series of travel notes, but in some cases going back through decades. Although I deliberately avoided pinning my appeal to any future book, I do now also have the beginnings of an idea of how to use these notes as a truly valid companion to Jupiter’s Travels. I’ll be developing these thoughts as this series draws to an end this coming summer.

From My Notebooks In 1973: Aswan and Lake Nasser

Finally convinced that there was no hope of getting permission to ride up the Nile, I bought a train ticket to Aswan. I had become close to Amin, the hotel manager, and he confided in me that he was planning to escape from Egypt and go to Brazil, where he already had an older brother, a doctor, established in Campinas, near Sâo Paulo. Legally, he was supposed to do years of military service first, so he would have to leave only with what he could carry. He asked me if I would carry with me, on the bike, his father’s ceremonial sword and deliver it to his brother when I arrived there. I was touched by his confidence, and the sword, in its scabbard, took up residence alongside the umbrella.

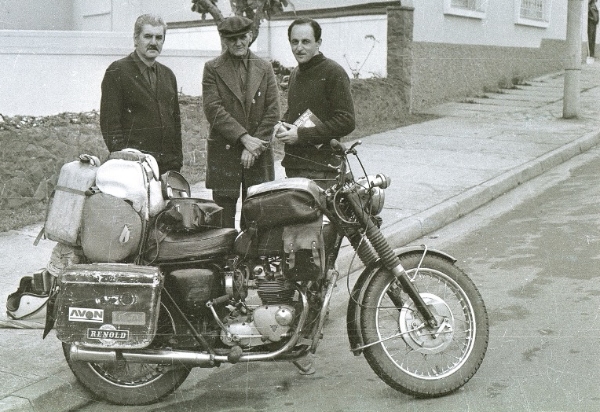

I got to Campinas nine months later. Amin had already arrived. That’s him on the right.

And this was me, holding on to the umbrella.

Meanwhile, back in Cairo, Monday, December 3rd

The train to Aswan. Cairo station – traders, stalls, cattle, crowds of persons waiting to coagulate round any seed.

Two references from Faris Serafim [Proprietor of Golden Hotel, Amin’s uncle]

Moatassam Bereir, influential, Khartoum, Foreign Office.

Mohamad Abouleila, Khartoum, Good family, older brothers know Faris.

[I did what I could to secure the bike and, with serious misgivings, entrusted it to the baggage wagon. The train left at 8pm. I was in a compartment with two Egyptian families who spoke almost no English but they had quantities of food for the 16-hour journey which they shared generously with me. We slept in our seats. In the morning I got breakfast in a saloon car and watched the passing scene. The train travelled very slowly, stopping often.]

Company [of conscript soldiers] descends at Essna. [Reminded me of my own national service.]

Just like UK conscripts being shuttled about, showing no sign of anticipation. Wear heavy khaki like us, plus suitcases, etc.

[Looking out at villages.] Stuffed animals over doorways, lizard, a fox.

[I had thoughts about the evolution of pyramids. Why that particular angle.]

My pyramid theory. Natural form of erosion in Upper Egypt. Rocks have caves in them. Measure angles, etc. Maybe some corpse was found in a cave in goat milk. [What was I thinking?]

In front of some villages, stones stood on end, curious effect immediately noticeable, but why? Not big stones, and all shapes, six inches to a foot, but all unnaturally upright. Still don’t quite know how water wheel works. i.e. don’t know what it discharges into.

[The train stops.]

Three peasants working on a plot of earth beneath window of train. As usual earth divided up chessboard fashion with foot-high dykes around 3-metre squares. Two men were chopping vigorously at earth, one old, one young.

The old man was tough and skinny and wore absolutely nothing beneath his galabeia which became evident when he bent down towards the train. Standing by them, with a five-foot cane pointing at the earth was the most imperious lady I have seen. The mother of all the pharaohs. In black, with black headdress, old but refined, face as strong and vigorous as ever. Tall, straight, irrefutable authority. Head a perfect long oval, mouth in parentheses which seemed on the point of curling down in contempt.

Tuesday, December 4th

Train empties at Aswan and waits. Then on to lake. Unloading is easy enough, though the attendant stands studiously while I hump my bags, then solicits a tip (which I give him, salving my pride by halving it.) From the platform have to drive bike down some steep steps. I let go a bit soon and on the last bounce I lose control and fall into bushes. Malesh!! Short and ineffectual interrogation by soldier, and I follow my self-appointed guide (an Arab Merlin figure) to the stony shore where some people are gathered outside s group of shacks, milling about among bundles. I have a ticket but must pay for the motorcycle. There is one shrewd fat Arab sitting outside a cabin, surveying the mob, while his men work. I give them the correct weight of the bike. and they charge me E£5 without weighing it. Passport control is simple, and the vehicle control looks straightforward, but I’m beginning to wonder how I’m going to get my bulky objects through customs, which is besieged by camel drivers carrying huge canvas and leather bags which I presume they sling over their camels. The carnet man indicates that an amount of money will help me over their problems and I succumb, with half a pound. In fact, if I had known how useless my pounds were to be I’d have been less precise. However, I was through and down to the boat in a flash and forgot completely about changing money.

The problem at the boat then obliterated any other concerns. It was immediately clear that it would be [all but] impossible to get the bike on the boat because my boat was separated from me by another boat. [They were parked side by side on the embankment.]

The first problem was the conventional one – of lifting four cwt down three feet, then to manoeuver it through a narrow passage packed with camel drivers in a terrible hurry. While manoeuvering it round a sharp corner all I lost was one pannier. It was just a matter of persistence. But the final crossing [to the other boat] was inconceivable. Both ships had steel-sided gangways, with openings only wide enough for a person, and the openings did not coincide either with each other or with the end of the passage. The bike had to be manoeuvered through a Z-shaped path, in mid-air at an angle of 30 degrees pointing downwards across three feet of water.

But for the sky-hook that appeared halfway through I think the journey would have stopped there. Even so the bike was resting most of the time on the remaining pannier or the foot brake pedal, which assumed a distinctive slope. There were five people struggling, and I was least use since I couldn’t understand the others. Finally the project passed out of my control, and I had to hope for good luck as I saw the exhaust manifold within an ace of being ripped from the cylinders. The experience affected my view of the boat, which I saw as cramped, dangerous, expensive and inhospitable. The deck, which I had imagined open to the sky, with chairs, was below with no chairs, or indeed anything but refuse and bare steel. Some cars had been brought on from the other side when this boat had been against the bank, and filled most of one half. At the other end, behind some corrugated iron, was a man brewing tea. A desk in front sold chits (or scrip, or torn bits of used paper) but of course took no Egyptian money (except from Anthony because he’d paid for first class.)

[Anthony was a young Dutchman, travelling with his wife.]

Every other floor space, except for a narrow footpath, was resolutely occupied by camel drivers who had their bed bundles down while I was struggling [with the bike]. As the journey advanced it became increasingly difficult to distinguish the people from their luggage. The grimy galabeias merged and an occasional limb or head protruded here and there. Most of them stayed, scarcely moving, for three days and two nights, while drifts of scrap paper, cigarette ends, orange peel and dust, all bound together with spit, built up around them.

The sight of people letting loose a jet of spit on the floor where they sleep is so objectionable that it goes beyond disgust to sheer wonder. How can they? But if you consider the desert your natural home (where spitting is not only harmless but quite natural) then being inside a house or boat is scarcely significant. Considered alongside the meticulous and lengthy rituals of spiritual cleansing which these same drivers undergo every day, it is hard to say who comes cleaner out of the wash – they or the European.

Two nights and three days floating across Lake Nasser.

A view of the first class boat from the third class. I soon joined them, on the roof.

It became clear that there would be no room to sleep even in these conditions, but the other boat which was all but empty was said to be for first class only. However, Europeans obviously have a natural exemption to class restraints in Africa. Should I have stuck with the drivers? It was not a productive thought. Other Europeans would not have allowed me even a faint chance of an understanding with them on such a short journey. I smuggled myself instead on to the top deck of the first-class boat, and I slept out under the sky. Bright moon. Stars becoming familiar. Cold at 3 am but not too much so. Spent time talking to Australian Mike – Macdonald. Something about him remained alienating to the last. A conflict of styles? His funny hat – a Moslem cap – was aggressively incongruous. The forthright manner was not quite true – and concealed a complex and uneasy personality. Protestations of easy independence were contradicted by heavy point-scoring humour, and he lost few opportunities for self-congratulation. Yet there is a wistful, touching desire to find peace with himself (which he failed to find in his monastery.)

Although the Dutchman wielded an equally heavy sledgehammer, he seemed to have found more peace in his 26 years. He and his wife Alice were travelling to South Africa to visit her father (?) It was her idea. He had wanted to holiday in Norway but now he was finding much reward. His treatment of his wife was very masterful, and she was obviously devoted to him, even when he scolded her like a father. A big man, studying “marketing,” son of an old family, with a natural confidence which could make him boorish and pigheaded, but for the moderating influences [of his wife] which he is happily able to accept. He was taken by my idea of classifying people as “alive or dead” but said he would have to study it.

Train from Cairo 7E£n+ 6E£ for bike. Left Cairo 8pm. High Dam 1.30pm Boat from Aswan to Wadi Halfa 2E£ 3rd class + 5E£ for bike. Spent E£5 on boat. Train Wadi Halfa to Atbara 3.60 S£+ 3.61S£ for bike (200kg)

Total £24 sterling.

I’m taking a week off, so in two weeks: Atbara and the desert.

Merry Christmas.