From My Notebooks In 1973: Into Sicily

12th October 2025 |

If you read last week’s notes about Zanfini, you would probably like to know what became of him and his project. I returned to Roggiano in 2001 and wrote about it in Dreaming of Jupiter. I have reproduced some of that at the end of this week’s notes. For more you might like to buy the book.

Friday October 19th , Leaving Roggiano

Now just a matter of making distance to get to Palermo. Have only a sketchy idea of distances in Sicily. Think it’s pretty small. Partly the effect of Mercator’s projection, but mainly through insular whim concerning islands.

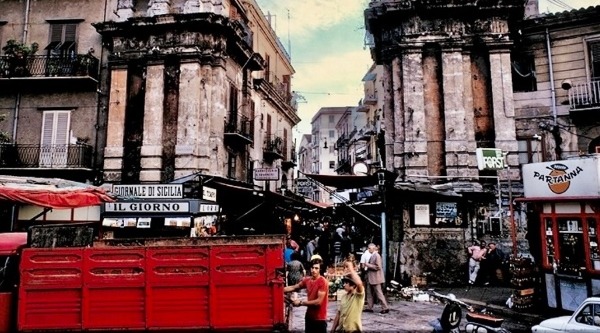

Ferry crossed from Reggio to Messina at 3 –3.30 pm. Cost 700 Lire (150 for person) Carries trains and cars. Rails on wood warped into barrel-shaped sections between rails. At other end, straight on to promising Autostrada missing Messina altogether. In the event it was 150 miles of which perhaps 25 were motorway, the rest sinuous coast road with patches of “original” Italian road surfaces. One and a half hours of daylight driving, three hours in dark following a car or a truck. Into Palermo itself, a half mile of cobbles. Arrive at 8pm, very far gone.

Mentally, when I get off the bike after a long ride, although capable of thought, I feel almost incapable of initiative. I want to reach immediately for the nearest source of rest, food and security. And this is where the act of motorcycling can impose an unusual perspective on life. Can make a prince feel like a peasant.

First of all, it is almost impossible to ride hundreds of miles with traffic without getting filthy and feeling it. Second, and I speak now about cities, you can’t leave the bike. Assembled on it is your universe, a natural target for thievery. Like a Christmas tree it glitters attractively and has presents tied all over it. You and it must be inseparable. You can’t lock up your car and melt into the crowd. You must attract the crowd, and the crowd becomes your enemy and your salvation. Because somewhere among the curious children and adults is someone who will help. But who to trust? How to convey your meaning with few words in common? All these things require patience, reserves of goodwill and imagination, which are precisely the qualities you’re least able to call upon. In summoning them up you dig into your own personality and painfully a sort of truth emerges which represents you, not as you would like to be seen, not as you think you ought to be seen, but as you are.

October 20th, Palermo

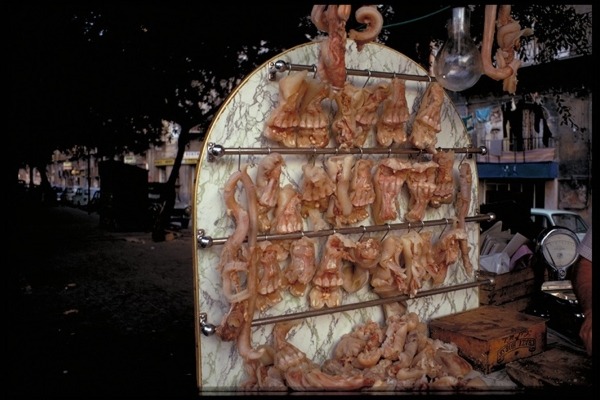

Yesterday I arrived in Palermo slack of face, filthy of garb, and reached immediately for a telephone to call the friend of a friend. Then sat in a bar and waited. Why did the large, fat man sitting outside playing cards warn me to keep my eye constantly on the bike? Why did he want to help me find my friend? What about the Israeli who came up and said he was trying to find out whether he would be jailed if he went back to Israel now? What about the German-speaking waiter? Wouldn’t any of them have helped me towards food, bed and stable? I was glad to have my friends, to be taken to a grand restaurant, fine pasta and grilled fish. What did I miss?

Today I can view Palermo as a tourist – but last night, on the via Torremuzzo, I saw it as a film by Visconti or Fellini – a set piece of villains, freaks, saints and brawlers in the night.

Priorities

1. Ferry booking, Peter Harland, LBC, ST Notes and film, Triumph diagnosis.

This is a coded inventory of anxieties. I am obviously destined to live with them for a long time, but it contradicts the habit of a lifetime. Somehow I will have to learn to enjoy what my senses can grasp and not draw them in like a frightened snail until I’m sure it’s safe outside. Is this possible at the age of 42? I’m definitely up against time now – time spent and time to come.

2. Will the Tunisians let me in?

How will I recover my deposit from the piratical Tirrenhia [The shipping company] if they don’t? What on earth will I do if they don’t?

3. Why is the Sunday Times telex number wrong? UK MOTNE LONDON indeed!!! Cost me 500 lire for a nonsensical waste of time.

4. Will I ever get through to Harland?

5. Is there something very wrong with the bike if it does three pints in a thousand miles? Obviously.

6. Can I cure it alone? So on and on.

Each problem solved opens doors to new ones. I must find it in me to go on solving them and still say – To hell with them! Obviously though if I’m to keep going on the money I have, I must keep out of big cities most of the time.

[A week or so before leaving England, Harry Evans, the Editor of the Sunday Times who also rode a bike, arranged for us both to get schooled by the motorcycle police. In those days it was still a rule to give hand signals.]

Sergeants Farmer, Fittal, and Easthaugh, I’ve been thinking of you. Every time I take the wrong line on a bend or find myself hopelessly confused between wanting to twist the throttle and signal with my right hand; I feel your eyes heavy but benign on my neck.

“He’s a good lad,” they say. “He’s trying, but he’ll never be one of us.”

Who are those three dashing sergeants? They are all at the police driving school at Hendon, and I was privileged to spend two days with them before leaving England, to see what motorcycle policemen are made of. The experience had a profound effect on me, which extended far beyond mere motorcycle matters. I learned for the first time in fifteen years of miscellaneous driving what that boring old highway code was really about; what it feels like to be safe on the road. As a motorcyclist I feel much more competent to stay out of trouble, but if only car drivers could get just a glimpse of the dangers of the road as a motorcyclist sees them, I would be elated. I include myself. Three months before leaving on this marathon I was an ordinary driver on four wheels. What I did then makes me shudder.

For one thing, car drivers fondly imagine that a motorcyclist can always squeeze by somehow. In fact, on two wheels you take your life in your hands on many roads going to the edge to avoid a road hog. On country roads particularly where there is often loose grit or gravel at the edge. I’ve fallen twice in this way, fortunately at slow speeds. Once at high speed and face-to-face with a four-wheeled assassin filling my side of the road I was just lucky.

Then car drivers suppose that other drivers trust them to do the right thing. On a motorcycle you dare not trust anyone. If you see a car rushing up towards you on a side road, you can’t afford to assume he’s going to brake at the last moment. And the avoiding action you take, whether you brake, swerve, or accelerate, is likely to carry its own risks. Car drivers who signal badly, or not at all are a hazard to all traffic, but to motorcyclists they are positively lethal. And so on and on. . . . . .

[Well, here endeth the lesson. I don’t think even police riders do hand signals anymore, and my feeling is that car drivers are generally more controlled today than they were then, more by regulation than by themselves. But you still dare not take your eyes off them.]

I wanted to reproduce here what I discovered in Roggiano in 2001, but to my surprise and disgust Adobe has locked me out of the pdf files of my own book, and I have no time now to sort this out. Suffice to say, when I arrived Zanfini had been dead just a few years. A school in Roggiano had been named after him. His widow was curiously reticent to talk about their history. I formed an opinion, quite unfounded, that there had been some strain on their relationship, and that it might have had to do with the young woman dressed in black, who had so impressed me when I first arrived. At any rate, Zanfini appears to have succeeded with his program, and was well remembered, but the buildings so ardently created, were now obsolete and derelict.

Cheers, everyone, until we meet again.

Ted