From My Notebooks In 1973: November

30th November 2025 |

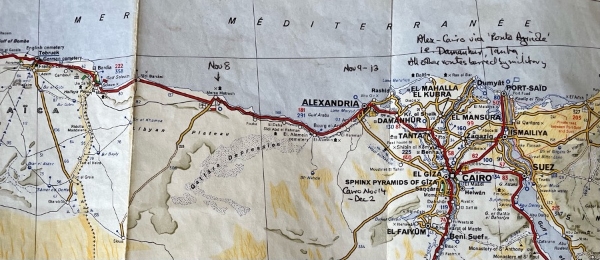

Here’s a portion of the Michelin map I used at the time:

Against the odds I’ve got through to Egypt, and in Alexandria put myself though a crash course in engine repairs. But there were papers I wanted, still coming to Benghazi from the Sunday Times. The owner of the garage was going to Benghazi and said he would get them for me.

Tuesday, 13th

I give my message to the Libyan at the garage. He refuses my Egyptian pound. Says he will pay. Shames my earlier opinion of him. (Although he certainly sought to impress me with his Mercedes). He lives in Barce. Take pix of garage men. Put in new roll of Kodachrome. In my tourist suit I sauntered forth, bristling with Pentax. The feeling was dismal. Suspicion, dislike. Was taken to task for photographing a lady with two children begging across the street. The man followed me for a block, until an older man interceded. “Portez-vous bien,” he said. “Vous pouvez photographier les hommes s’ils acceptent.”

Onto the promenade to take pic of front. Iron grip on my right arm, shouting, instantly surrounded by people. Man in T-shirt, pullover, brown trousers and sort of fez-cum-cap. Face distorted with anger, suspicion, certainty that he had the enemy in his grasp. Shouted for police. “From where you come?” London, I said. “No, no,” he screamed. Soldiers arrive from Navy post right next to me. He insists that they pin my arms behind my back. There is obviously some difference of opinion about the gravity of the matter, but I am marched off to the barracks. Once inside everyone is at great pains to make me feel safe. Captains, majors, and a colonel smile at me and ask me not to let this change my opinion of Egypt. Eventually I am carried off to the general. He sits dignified, dyspeptic, myopic, behind desk loaded with (among other things) medicines. (Parendravite, in pack, other bottles of nameless draughts or lotions). Slowly he peruses my passport, my paper of permission, my ST cutting. Remarks on telephoto lense. I unload the camera and give him the film. Can’t say I mind. The pictures were not dear to me. The major copies down all the details. Then next door, tea with an army brigadier. Asks friendly questions about my journey. Both brigadier and general saw the publicity value to Triumph. He lived in Knightsbridge for two years, next to Harrods. Drive back in blue jeep.

Headquarters spacious, but nothing remarkable. Offices all have army beds made up for the night. Some sense of discipline. Not a bad impression. Walked away looking for my citizen-captor but he had moved on.

Wish I could say I was frightened, but not so. The first moments surrounded by small mob shouting in Arabic, I simply thought, “Well you meant to provoke something, so now we’ll see what happens.” My concern was mainly that it might embarrass the Sunday Times in Cairo, or the old lady at the Pension Normandie. Still hope nothing follows from the incident.

Return to hotel to shed my embarrassing emblems of spy/tourist – the jacket and the Pentax plus lenses. Pull on sweater and walk off to find an older area of the town “quartier populaire.” Not far away I plunged into a narrow street blocked by a lorry. Men passed by grunting under the weight of sacks full of empty cordial bottles. They were being stacked in a “cave” There were may have been up to sixty sacks full. Street level, the houses have doorways and separate lockup areas suitable for small shops open to air, or workshops. In one, two men worked on a great heap of straw or reed, making brooms. Outside another, looking like the debris of a vanished civilisation, stood a number of gilt chair frames as used for public receptions and fashion shows, and a number of people were more or less busy stuffing the seats. A boy passed with a tattered basket of leather straps. A small boy was counting his small hoard of piastres and little notes on the pavement. Fruit, grain merchants. One had a display including corn, whole, broken and ground, dried beans of various kinds including one that swarmed with weevils. I pointed them out and the shopkeeper seemed quite pleased with them. “Sousse,” he kept saying. The beans were for making “fool” as it’s pronounced, a delicious imitation of spiced minced meat, rolled and cooked in sausage shape. Sunflower and sesame seeds also. Then some young people gathered about me. Up to then no-one had approached, and although I was probably being observed, had not realised it. They asked something and I replied as usual that I was English. Then a man with dark blue jacket with leather elbows and mourning strip on lapel asked me for my papers. [They lay the left arm across their upturned right fore-arm and display the right hand. This means “papers.”] but in changing my jacket I had left my passport at the hotel. A certain amount of excitement was noticeable, and I was conveyed through several hands along the street, each one looking more disreputable, although obviously of higher rank. All unshaven, nicotine-stained, coughing. Chain-smoking in Egypt is endemic from the age of seven. Crowd gathered. Several called out “Yehudi”, but as question rather than a menace. Put down in chair outside café. Do I want coffee? Tea? But not so friendly. Just formality. Crowd again. Proprietor throws water at them. They scattered and reformed, everyone coming to look at the Jewish spy. Eventually the chief takes me to his “secret” office. Worthy of any exotic spy film – a hutch buried inside a building, airless, windowless, ceiling barely eight ft. whitewashed, 8ft square, Desk. Pictures on wall of groups of soldiers. One group certainly of British officers in tropical shorts, etc. On desk a montage of magazine cuttings of girls, like soldier’s locker door. Made to sit facing door with my coffee brought to me. Faces kept coming and staring straight at me, long and without expression. By now I felt the crisis was over, but when I was first hustled in there I was ready to expect anything. Nothing is so unnerving as to be propelled into a small space by a noisy crowd you can’t speak to. At last I was ushered out again into a shabby sedan and sandwiched in rear seat between two police in very plain clothes. Three young men in front seat turned out to be chief’s sons. To Police HQ. Made to stand before young, moustachio’d detective who failed to get the Normandie by phone. So off to the hotel to get my papers, although by this time it was clear they had caught no big Jewish fish, but a British boot, which might nevertheless be booby trapped. Even then, having examined my papers (of which the Sunday Times cutting was by far the most persuasive) I was returned yet again to HQ to be formally dismissed with an apology and returned once more to my hotel and the genial M.Pacaud whose appetite was now thoroughly aroused, and equaled the one I had found for a delicious lunch of fish mayonnaise and moussaka.

M.Pacaud’s version, delivered with gusto to the others, was that I had set out in the morning, determined to provoke an incident, with cameras and an obviously sinister wardrobe, and having failed to arouse any interest had climbed onto a pedestal and pointed a telephoto lense at a Russian submarine in the harbour. However my arrest by the Navy having been disappointingly civilised and apologetic, I had returned to the hotel, changed my jacket for an Israeli sweater and, deliberately leaving my papers behind, had sauntered off to the toughest neighbourhood available and behaved as much like a spy as possible while also drawing a merchant’s attention to his infested wares. All of which provoked much laughter and had a grain of truth to it. But Pacaud’s story of the Italian journalist who was sentenced to ten years’ hard for taking a photograph from much the same place suggests that I may have got away lightly.

This curious cave was shown to me by Sa’ad, near his house in Benghazi. The inscription carved into the rock above the entrance, he said, identifies it as a refuge for Jews, but he couldn’t say in what period. Does anyone know?

[As all these events and meetings followed hard on each other I was struggling to make sense of them, trying to find words that fit.]

If and when my fate allows me to complete this singular excursion, what will I have to tell my fellow men. What knowledge will I have that is not already theirs. Or if not theirs, ignored deliberately. I shall say that you may meet any man in the world face to face, one to another, and if you take care to stand on level ground you will meet sympathy, goodwill and generosity. But if you set yourself apart, or above, or allow yourself to be one against many, fear may intervene and produce alarming distortions.

Like any growing thing, a meeting between men flowers from a seed that must be delicately sown and nourished. There is no crash programme, for though the stages and seasons may succeed each other in the space of a moment, each one must have its space and be given its time.

Next week: To Cairo and the Pyramids