From My Notebooks In 1973: Sudan to Ethiopia

18th January 2026 |

From the desert to the mountains.

Those days crossing the desert in Sudan were among the most influential of my life, an apotheosis. After my abject performance on that first day, running out of fuel and water and burying myself in sand, the schoolteachers of Kinedra lifted me up and made a hero of me, and from that day on I was treated with the utmost generosity and respect.

My interlude at the tea house among tribesmen of various kinds simply reinforced my admiration. Like every westerner I had heard no end of stories about Arab deviousness and thievery. I took the accounts of their nobility by Lawrence, Thesiger and others with a pinch of salt. Now I had to concede that in their own element they were splendid. The simplicity and respect in our communication was balm for the soul.

Of course, it bothered me that I never caught even a glimpse of the headmaster’s wife. A world in which women were invisible would quickly become intolerable to me, but I was passing through their world and had to accept their customs. The fact that the Bescharyin were all huddled together in the same truck bed, men, women, chlldren, and a foreigner, was proof that custom can give way to necessity. As I was to learn during the following years, it is custom that rules the roost everywhere, however much it is attributed to religious belief or idealism. Arbitrary custom cements society, and it can only be broken by often painful necessity.

Look to Iran for grim proof, if it is needed.

Now the journey continues…

December 13th 1973

From Kassala. Along the railway line. Cracked dry mud. Much of it corrugated. Seemed bad at the time except for some flat stretches where a secondary track close to the line could be used. Before Kash’m-El Girbar, bridge and switchback road.

At a tea-house in Kashm-el Girbar I emulated this man and ate a large piece of delicious Nile Perch, while other customers gathered round my bike. “How quick? How fast?” they demanded. When I was ready to leave, someone had already paid my bill.

From K.G itself I was promised “queiss” track. It was terrible – true washboard all the way. Slept with camels 15km from Gedaref.

[In fact, I spread a sheet on the ground a little way from the track and slept on it, to be woken in the middle of the night by a small caravan of camels travelling over me. I looked up at their huge bodies as they daintily avoided stepping on me.]

December 14th

Next day crowds in Gedaref were oppressive. Left straightaway and found road now worse than ever. Some washboard, but mostly deep ruts – one or two feet, leg-breaking and bike-throwing.

Always having to choose a rut only to find it narrowing, unable to get out. Dropped bike three times, one very difficult– have picture.

So to Doka. Night with police.

[Someone had told me there was a police post on the road to the Ethiopian border town, Metema, and they could be trusted, so I slept on the ground inside their compound.]

December 15th

On to Metema, same road, plus rocks, dips etc.

Went to “best hotel in Metema.” Last night. Corrugated iron roof, rough plaster walls on wooden uprights, earth floor, bar with shelves of drink, owner at small table, upholstered chairs and sofa round another table. First upholstery seen since Egypt. Woman shakes my hand and it comes as a shock to me. I have forgotten about women in public – it’s over two months. At first the impression is charming. Dresses of cotton, knee length – a bit dirndlish. They smile, laugh, suggest that life is a light matter, but in the morning it’s less pretty.

December 16th

Morning in Ethiopia. Camel with small flock of birds on its back. Brillian red beaks, grey and white plumage. Another camel with two men sitting back to back, the rear passenger in bright red blanket (Peruvian?) Both smiling. Huts round, of brick, with conical straw roofs, some tied at top. “Hotels” and “bars”. – women with inviting smiles. The women nursing their illegitimate children and their tightly rolled wads of Ethiopian dollars. Later I notice that it’s the girls who are first to stretch out their hands, and it seems that in this country the women take onto themselves the stigma of sin, avarice and corruption. Leaving the men to enjoy a lofty nobility. It may become clearer but one thing is already clear. The relationships between the sexes, however they are customarily managed in different countries, produce rich and extraordinary phenomena.

I was overjoyed to arrive in Metema yesterday, because it marked a solid step forward. Today it rather disgusts me. I can think of no reason why anyone should want to be here except to cash in somehow. Is it a typical border town? Evey hut is a ‘bar.’ Every building bigger than a hut is automatically a “hotel,” with a rectangle of painted metal slung over the door to say so (usually blue or red).

Dawn breaks outside Metema

The customs say I must wait until 3pm. Thought overwhelms me with horror; The travelling is so hard I have to keep moving, just to keep up some sense of achievement to balance the hardship. I listen to a policeman who says I can do customs in Gondar and set off into Ethiopia.

Had a glass of something by mistake when I asked for bread. Yellow tea, with a familiar taste that I couldn’t place and didn’t much care for. (Although it was faintly reminiscent of Bovril.)

Following day, Metema to Gondar. Road vastly improved. i.e. like a normal cart track. Then fords – 1 and 2, terrifying – 3,4,5. Then very steep climbs, very hot. Bike stalls halfway up. Have to carry stuff to the top.

Sometimes the rock is black, sometimes pink which powders into dust. The light wipes out all contours when it hits the dust – can see nothing but a sheet of glowing pink and white. The improvement in the road was illusory. In its own way it was as bad as any. Steep rising and falling road, loose rocks, desperate dashes into fords and up the steep exits, overheating until engine fails. Twice on the ground within a minute. Near exhaustion at times. Back jolting is painful, left arm constantly wrenched when wheel spins on a stone.

Last big ford of the day is too much. Some men gathered to help and suggest I sleep there. They are building a bridge. I am about halfway between two main villages, have come about 100kms. Wash feet, body, socks in river. Drink some. Have tea with road gang; eat half tin of Sudan mackerel. Lie in bed listening to men talking round their fires. One man has voice that dominates with amazing range of expression. All the men, it seems, have two voices – a normal speaking voice and one that jests and mimics and plays on a higher register with very rapid, light consonants and cat-like vowels.

December 17th

Road continues. Leave the bridge builders early. This is the fifth day of my ride from Kassala. Every day the road has seemed just short of impossible _ and each day new difficulties.

[That night I recapitulated in my notebook what had happened in the last few days.]

I am feeling now as if I am being put to a series of ingeniously graded tests. First outside Kassala, the dust mud, cracked and ridged. – carburetor stuck at K.G. Then, after tea when the good road was promised, the washboard for seventy miles, a rattling and shaking that should have torn the machine apart. No relief – if anything becoming more severe. – until the sun moved into my eyes as the road swings to the south west and I dared not go on. Slept on the camel track. Next day washboard continues to Gedaref where I eat fish, drink tea, and get stared at, and escape on the road to Doka. Now the road is both washboard and rut. Sometimes the ruts are two feet deep and hardly that wide and one must ride through them with boots raised for fear of breaking legs against sides. Where the ruts are less serious the washboard becomes correspondingly more severe.

In Gedaref police station (why did I go there? Heaven knows) I met an African refugee from Rhodesia. He said the police at Doka were nice, so when I get to Doka after seven or eight hours driving, I accept the chance to stop honourably. From Doka next day, to all the other hazards are added steep inclines covered in loose rocks. It’s important to remember that these are not consistent hazards. Anything can happen at any moment. It is dangerous to take one’s eye off the road for an instant. I have gone over twice now, not through lack of attention but through taking the wrong line and being caught in converging ruts or in a bad bit of rock. So I am ready for anything and still dreading it. Even inventing impossible hazards for myself, only to see them realised. The impossible ford, the rocky path along a ravine, etc.

Why no puncture? Why don’t the tyres tear to shreds? I think that might finish me. I am full of admiration for the bike and tyres. Why doesn’t the Triumph just die? It has no need to go on, unlike me. It protests, chatters, faints, but always resumes its work like a faithful donkey. What havoc is being wrought inside those cylinders?

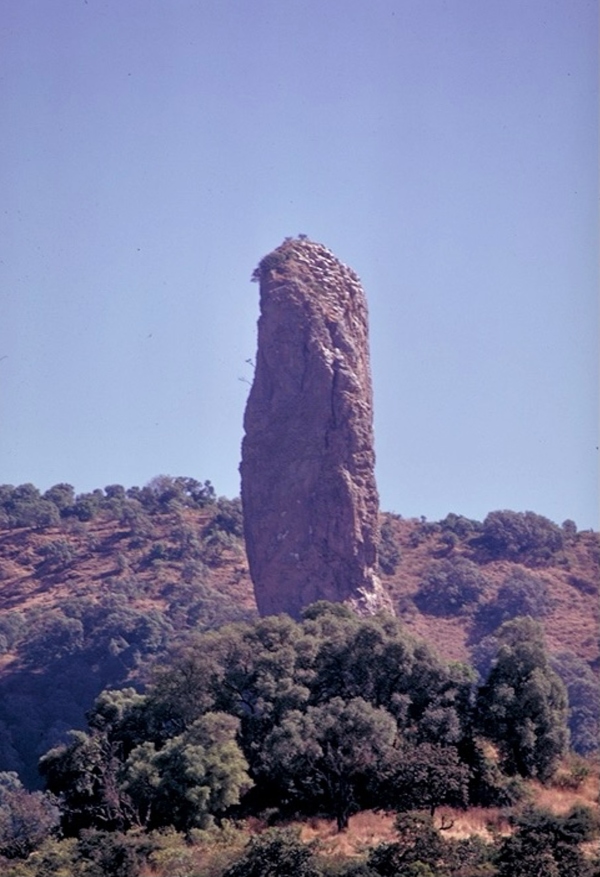

On the third day I passed this extraordinary pillar of rock. I saw it again, unremarked, when I went past 28 years later. I wonder if it’s been given a name yet.

It’s becoming more and more difficult to do “business as usual.” A lot of people ordered books from me before Christmas, and it was a little while before I discovered that Trump’s tariffs had thrown a spanner in the works, and all the books I sent to the USA began coming back to me.

I’ve refunded the majority of those who ordered them. The postage, which came to roughly 300 euros, is lost, of course. Fortunately, many of you responded to my “Subscription Offer” so I am certainly not complaining. I can’t resell the books because their all dedicated, but I’ll keep them, so if any of you happen to be passing by in the next year or two, you can drop in and pick yours up.

Cheers, Ted.