From My Notebooks In 1977: Pakistan and the Khyber Pass

20th July 2025 |

Still with the brothers at Jhellum Bridge.

May 8th

The breakfast ceremony is a continuation of yesterday. Parathas, French toast. Hamid ever watchful, suggests that paratha leaves a burning sensation in the stomach. Too much food?

I take two family portraits. The hookah is out of place – the wrong kind for Pathans. A Punjabi policeman insinuates himself with it. My mistake. Hamid is patient, but disapproving.

During the day beginnings of a great lightness of the spirit, a reawakening of joy. At the border I watch each step with suspicion, hope, anxiety barely concealed – like one escaping from a maze. What are the indications? Fewer people, more space, less detritus as the watching multitudes recede. Now there are individuals, recognisable people.

Road to Rawalpindi. First much eroded land, then farmland. R has a very well-ordered look – at least in the cantonment area. At Intercontinental [Hotel] I drop in and ask for Clifton. [Who? I don’t remember him.]

“Yes, he’s registered,” but has gone to Taxila by car. I am not going to risk an anticlimax while the going is good. I leave a note, and on to Peshawar.

Good roads. 50mph. Over the Indus where a huge fort dominates a confluence (as at Mulhausen?) At Peshawar find myself outside the Intercon. again. Ask here for cheap hotels. Very helpful. List of four. Dean’s; John’s; Park; and Sharazad. Starting at 135 rps to 35rps.

Doorman has hennaed beard. Outside Nazeer is taking the air. I talk to him. He offers me hospitality. Everything pours out of him in a burbling stream of words. His life, his romances, his poetry, the praise that has been heaped upon him, his career at the hotel, the army. He needs only an audience. I know I must ration him. Escape to eat at Al Shiraz. There I meet the owner’s son, a man of considerable conceit, barely contained, in blue tunic and trousers. A minerologist, who prospects for ores and gems. He does not believe in God. He has travelled. He understands the international political scene. He knows there is a plan afoot to disrupt Pakistan though he doesn’t know where its headquarters are. In the meantime he always makes his own track, because where there is a man-made track people will always have reported anything there. On the other hand people are very ignorant of the possibilities. He found diamonds where some villagers were living and showed them. They had seen them but were not interested. He always takes company on his treks, but only to divert himself. They trek 35 miles a day. He never leaves a mossy stone unturned. My flattering attention earns me several cups of tea from fine china.

(Footnotes: Looking at a shaven Westerner in the Istanbul. “Bodhgaya is a long way to go for a haircut,” and, “The truth is a matter of degree.”)

Peshawar: Two stories, narrow wooden balconies protruding in old houses. Narrow alleys winding uphill. Kebab roasting, fanning charcoal, cow meat on display, impassive detached faces. Fairly quiet.

Arif on sexual starvation: “The Indians were our slaves” – to explain the low value they place on individuality.

“Indians are very superstitious.”

“Prostitution must be allowed, otherwise prostitutes will mingle with society and corrupt the innocent.”

“Children must be taught to fear their elders. I have made my children afraid of me. Deliberately.”

“Our women are naturally modest. They do no wish to mingle with strangers, particularly men, so they do not go out of their home aimlessly.”

“Now there are women doctors, lawyers, etc. and girls get a better education. The men do not resist too much.”

He climbs the mountain opposite every morning and night. All is very deliberate, to prepare for the next moment. No room for surprise. Is that why visitors are made so welcome? The village elder was there. I was asked to account for Hippies. There was some spitting through the lattice work of the beds, and Arif washed his mouth out on to the floor.

At first he was wearing crumbled blue shirt and trousers. Later changed into white trousers and top with waistcoat and skull cap. We ate mutton boiled and fried, in sauce with onion. Also some egg fried and roti and tomato.

Monday 9th

To Dara.

Tuesday 10th

To Kabul, through the Khyber Pass.

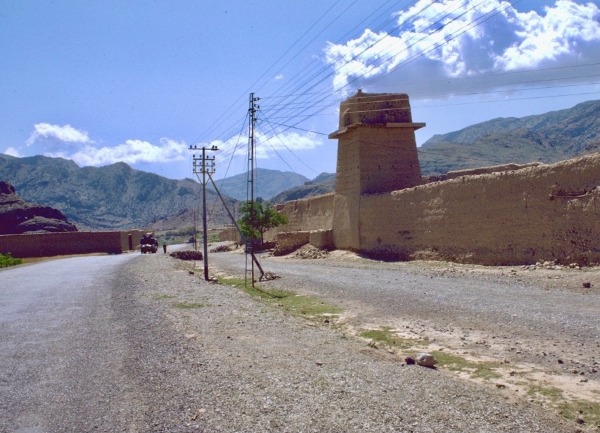

The famous Khyber Pass

Not impressive at first but later as I stop to take pictures some hostility. Frontier not too bad. $10 insurance.

[I arrive in Kabul.]

I’m looking for milk in Chicken street. The shop sells yoghourt, sausage, bread and milk. “Have you got fresh milk?”

“How much do you want? A glass?” I hesitate.

“Two glasses?” A pause.

“No milk,” he says and turns away. Not physically, but I cease to exist.

“One glass then,” but he is not aware. He walks through me, very close, to argue (is he arguing?) with a man across the road.

“But you said . . .” and he’s in full spate. On the doorstep I turn to face him, to make him pay attention. Impossible. I am not there. What a strange power. I’m outraged, indignant, humiliated (so often) I could hit him. That’s all. There seems to be no other response. Hit – – or run. I run – – at walking pace, reflecting, trying to overcome my seething resentment. On my bed, lately infested with bed bugs now lying on their backs below and still feebly brandishing their limbs, I am thinking about the uses of power. Should a person develop all his capacities to the full? Then power, backed by the threat of physical violence, is one of them. (At the same time, disturbed by the litter of things around me I am fiddling to reduce their number. Why does it make me uneasy? Am I occupying too much territory? Am I afraid of retribution for this aggressive act? Or am I afraid that if I’m attacked I shall not be able to get my things together in time to escape? I would have to stand and fight. Same thing, fear. And as I think about it, I know it, because I feel the dread adrenalin.)

What if the use of violence is denied. Does that mean there is no power? Think of the legless cripple on the highway. What power he had, on his trolley, laughing in the face of the world, taunting it, defying it to do him more damage. The power in his face, square, lined, cut to short bristle.

And the other, of Pondicherry, like the stillest black hole on the pavement, sucks the whole universe in.

Suddenly I’m excited by what these two cripples offer and represent. Power and love, though both are denied any physical means to fulfill what they express or attract. Everything could be said in terms of these two. Did I really understand Grass? [Gunter Grass?]