Articles published in November, 2025

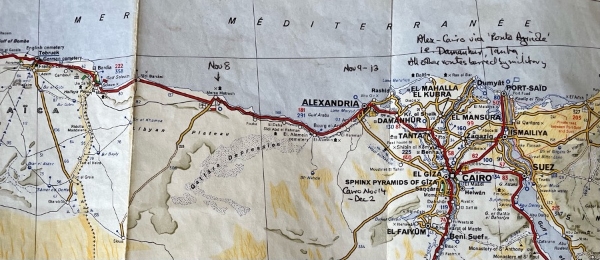

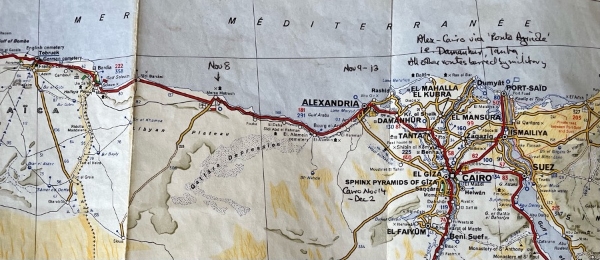

Here’s a portion of the Michelin map I used at the time:

Against the odds I’ve got through to Egypt, and in Alexandria put myself though a crash course in engine repairs. But there were papers I wanted, still coming to Benghazi from the Sunday Times. The owner of the garage was going to Benghazi and said he would get them for me.

Tuesday, 13th

I give my message to the Libyan at the garage. He refuses my Egyptian pound. Says he will pay. Shames my earlier opinion of him. (Although he certainly sought to impress me with his Mercedes). He lives in Barce. Take pix of garage men. Put in new roll of Kodachrome. In my tourist suit I sauntered forth, bristling with Pentax. The feeling was dismal. Suspicion, dislike. Was taken to task for photographing a lady with two children begging across the street. The man followed me for a block, until an older man interceded. “Portez-vous bien,” he said. “Vous pouvez photographier les hommes s’ils acceptent.”

Onto the promenade to take pic of front. Iron grip on my right arm, shouting, instantly surrounded by people. Man in T-shirt, pullover, brown trousers and sort of fez-cum-cap. Face distorted with anger, suspicion, certainty that he had the enemy in his grasp. Shouted for police. “From where you come?” London, I said. “No, no,” he screamed. Soldiers arrive from Navy post right next to me. He insists that they pin my arms behind my back. There is obviously some difference of opinion about the gravity of the matter, but I am marched off to the barracks. Once inside everyone is at great pains to make me feel safe. Captains, majors, and a colonel smile at me and ask me not to let this change my opinion of Egypt. Eventually I am carried off to the general. He sits dignified, dyspeptic, myopic, behind desk loaded with (among other things) medicines. (Parendravite, in pack, other bottles of nameless draughts or lotions). Slowly he peruses my passport, my paper of permission, my ST cutting. Remarks on telephoto lense. I unload the camera and give him the film. Can’t say I mind. The pictures were not dear to me. The major copies down all the details. Then next door, tea with an army brigadier. Asks friendly questions about my journey. Both brigadier and general saw the publicity value to Triumph. He lived in Knightsbridge for two years, next to Harrods. Drive back in blue jeep.

Headquarters spacious, but nothing remarkable. Offices all have army beds made up for the night. Some sense of discipline. Not a bad impression. Walked away looking for my citizen-captor but he had moved on.

Wish I could say I was frightened, but not so. The first moments surrounded by small mob shouting in Arabic, I simply thought, “Well you meant to provoke something, so now we’ll see what happens.” My concern was mainly that it might embarrass the Sunday Times in Cairo, or the old lady at the Pension Normandie. Still hope nothing follows from the incident.

Return to hotel to shed my embarrassing emblems of spy/tourist – the jacket and the Pentax plus lenses. Pull on sweater and walk off to find an older area of the town “quartier populaire.” Not far away I plunged into a narrow street blocked by a lorry. Men passed by grunting under the weight of sacks full of empty cordial bottles. They were being stacked in a “cave” There were may have been up to sixty sacks full. Street level, the houses have doorways and separate lockup areas suitable for small shops open to air, or workshops. In one, two men worked on a great heap of straw or reed, making brooms. Outside another, looking like the debris of a vanished civilisation, stood a number of gilt chair frames as used for public receptions and fashion shows, and a number of people were more or less busy stuffing the seats. A boy passed with a tattered basket of leather straps. A small boy was counting his small hoard of piastres and little notes on the pavement. Fruit, grain merchants. One had a display including corn, whole, broken and ground, dried beans of various kinds including one that swarmed with weevils. I pointed them out and the shopkeeper seemed quite pleased with them. “Sousse,” he kept saying. The beans were for making “fool” as it’s pronounced, a delicious imitation of spiced minced meat, rolled and cooked in sausage shape. Sunflower and sesame seeds also. Then some young people gathered about me. Up to then no-one had approached, and although I was probably being observed, had not realised it. They asked something and I replied as usual that I was English. Then a man with dark blue jacket with leather elbows and mourning strip on lapel asked me for my papers. [They lay the left arm across their upturned right fore-arm and display the right hand. This means “papers.”] but in changing my jacket I had left my passport at the hotel. A certain amount of excitement was noticeable, and I was conveyed through several hands along the street, each one looking more disreputable, although obviously of higher rank. All unshaven, nicotine-stained, coughing. Chain-smoking in Egypt is endemic from the age of seven. Crowd gathered. Several called out “Yehudi”, but as question rather than a menace. Put down in chair outside café. Do I want coffee? Tea? But not so friendly. Just formality. Crowd again. Proprietor throws water at them. They scattered and reformed, everyone coming to look at the Jewish spy. Eventually the chief takes me to his “secret” office. Worthy of any exotic spy film – a hutch buried inside a building, airless, windowless, ceiling barely eight ft. whitewashed, 8ft square, Desk. Pictures on wall of groups of soldiers. One group certainly of British officers in tropical shorts, etc. On desk a montage of magazine cuttings of girls, like soldier’s locker door. Made to sit facing door with my coffee brought to me. Faces kept coming and staring straight at me, long and without expression. By now I felt the crisis was over, but when I was first hustled in there I was ready to expect anything. Nothing is so unnerving as to be propelled into a small space by a noisy crowd you can’t speak to. At last I was ushered out again into a shabby sedan and sandwiched in rear seat between two police in very plain clothes. Three young men in front seat turned out to be chief’s sons. To Police HQ. Made to stand before young, moustachio’d detective who failed to get the Normandie by phone. So off to the hotel to get my papers, although by this time it was clear they had caught no big Jewish fish, but a British boot, which might nevertheless be booby trapped. Even then, having examined my papers (of which the Sunday Times cutting was by far the most persuasive) I was returned yet again to HQ to be formally dismissed with an apology and returned once more to my hotel and the genial M.Pacaud whose appetite was now thoroughly aroused, and equaled the one I had found for a delicious lunch of fish mayonnaise and moussaka.

M.Pacaud’s version, delivered with gusto to the others, was that I had set out in the morning, determined to provoke an incident, with cameras and an obviously sinister wardrobe, and having failed to arouse any interest had climbed onto a pedestal and pointed a telephoto lense at a Russian submarine in the harbour. However my arrest by the Navy having been disappointingly civilised and apologetic, I had returned to the hotel, changed my jacket for an Israeli sweater and, deliberately leaving my papers behind, had sauntered off to the toughest neighbourhood available and behaved as much like a spy as possible while also drawing a merchant’s attention to his infested wares. All of which provoked much laughter and had a grain of truth to it. But Pacaud’s story of the Italian journalist who was sentenced to ten years’ hard for taking a photograph from much the same place suggests that I may have got away lightly.

This curious cave was shown to me by Sa’ad, near his house in Benghazi. The inscription carved into the rock above the entrance, he said, identifies it as a refuge for Jews, but he couldn’t say in what period. Does anyone know?

[As all these events and meetings followed hard on each other I was struggling to make sense of them, trying to find words that fit.]

If and when my fate allows me to complete this singular excursion, what will I have to tell my fellow men. What knowledge will I have that is not already theirs. Or if not theirs, ignored deliberately. I shall say that you may meet any man in the world face to face, one to another, and if you take care to stand on level ground you will meet sympathy, goodwill and generosity. But if you set yourself apart, or above, or allow yourself to be one against many, fear may intervene and produce alarming distortions.

Like any growing thing, a meeting between men flowers from a seed that must be delicately sown and nourished. There is no crash programme, for though the stages and seasons may succeed each other in the space of a moment, each one must have its space and be given its time.

Next week: To Cairo and the Pyramids

Despite all warnings and expectations I came through the frontier from Libya with ease. Far from being shot on sight, I was treated like royalty. A valuable lesson. When it comes to borders you never know until you get there. But now I was in Egypt, at night, totally unprepared. My Michelin map has little to offer. Sidi Barrani, Mersa Matruh, El Alamein, Alexandria – just names from World War II. Rommel vs. Montgomery. Here’s what I noted, word for word.

November 7th

In the dark. With only polaroid glasses. What has happened to the visors? Both gone, in Benghazi with Kerim? Drive slowly through Salloum. Cows, several, in the street. Then on to Sidi Barrani. Petrol. Then police post 18 km from Matruh. By now I’m high on the certainty that I really am in Egypt. I’ve saved £55 and several days. Only problem is getting the letters from Benghazi.

Police stop me. Five minutes, they promise me, shuffling through all my papers. They keep passport then suddenly say I must drive, to Matruh behind that car, to the control. The car sets off fast. I put away papers, zip up bag, etc, and go. He drives at 70. Halfway there I reach for the rt hand pannier. Yes, lid has gone. Wallet has gone. Shocked numb, I stop, turn. And drive slowly on the wrong side back to the police post. Nothing. Yes. Two Peugeots have stopped, going each way. The drivers are out and looking at the ground. One waves me on. Incredibly, I go on. Why? I knew they must have found something. What else should it be but my stuff? But I obeyed his signal. Writing this is very painful. I can hardly admit that my nature is so feeble as to surrender so easily to an imperative wave of a hand. It bodes ill, I feel. Later I found the pannier top. Then further on, the truck driver who was helping saw first glove. Further on I found the second. Obviously the wallet should have been between them. Nothing. Demoralised I went on to Matruh. There I was given my passport. I went back to the road, determined not to let go.

Vaccination certificates, driving licenses, Amex card, cable card, picture of Jo, of mother and Bill, of me for visas. And money: Zambian, Ethiopian, Australian, Brazilian, American, – £30 in all. I have marked the distance from the place where we stopped looking. I drive back on the clock and set up a pile of stones. Drive on a mile, then work slowly back and forth. Nothing. Could the wallet have fallen first? Maybe, with lid only locked at the rear end it flew up and stuck, letting the wallet fall.

I drive back to the police post. The fat young Arab is not pleased, but he lets me look. Then I begin to search the verge from that point. Within fifty yards I see a bundle of papers against a shrub. Wallet broken. No money. No address section. No credit cards. Half of one license. No passport pics. Rest intact. Clearly the Arab found it, threw it away again before the police. If I had been able to speak Arabic he would have been caught at the police post. But it was a sad reverse after my triumphant assault on Egypt from the West. And ironic, after all the stories about Egyptian dishonesty. It is now 2 am, too late for a hotel. I am received by police patrol at Matruh and so flattered by their interest and sympathy that my morale is restored. A glass of tea, handful of huge dates, corned beef and bread. Then I’m offered a bedroom. The pock-faced Arab stays with me and engages me with Arabic lessons. Breakfast – Fetarr; Lunch – Redden; Dinner – Ashair. Week, month, year. It’s 4 am now, and the others have put on fatigues and built me a bedroom roofed by soft-board panels.

November 8th

I sleep well. Happy, all’s good and bad equally. So it goes on. Next morning I go back and find, where wallet originally fell, address pages and pics blowing in the desert. But no credit cards. A ten cruzeiro note and half a Tunisian pound. Halva for breakfast, the police on the road to Alex say “Where’s your special permission?” All crumbles before my eyes. Entry to Egypt is just a comedy. It’s the road to Alex that counts. Now they will send me back. The policeman says, No. In Matruh they will give you permission. I don’t believe it. Up to now all such official predictions have proved false. Why should I believe this one, because it’s convenient.

Well, they would have given me permission – if I hadn’t already got it. [I must have found it stuffed inside the carnet] That first meaningless scribble, performed by an illiterate, was the only paper that really mattered, the paper to carry me, as a foreigner, through the radar country between Matruh and Alex.

NOTES

Saved £55 – lost £35: Net gain £20 and three days.

A World War II relic in the desert: Not much, perhaps, but it affected me.

Alex is a labyrinth. Alamein has War II tanks but got little chance to see them. Good lunch + pint of beer costs 75p (English). Petrol about 25p a gallon. Pipeline under construction along the road. Ends halfway. Resumes outside Alex. Dia about 10”. Water, I suppose. Some asbestos pipe, some steel. Little military to see. Donkeys and camels to plough. Turn over top 3” of sandy soil. Plots here and there. Sea is a miracle of blue. Beach white. Cemeteries for everyone – German, Greek, British. Italian. “Manqua fortuna – non valore.” Many police controls – always friendly. Impressed by my newspaper cutting. Can’t gauge whether I’m first foreigner to come through.

Women now graceful. Poised. Balance tin cans of water on their heads, makes them seem precious as any pottery. On to Pension Normandie.

[I arrived in the centre of Alex. A tout directed me to a hotel on the top floor of one of the graceful buildings near the port. Called Pension Normandie, run by elderly Frenchwoman. Noticed smoke pouring from an exhaust pipe. Obviously there was work to be done.]

Monday November 10th, Alexandria

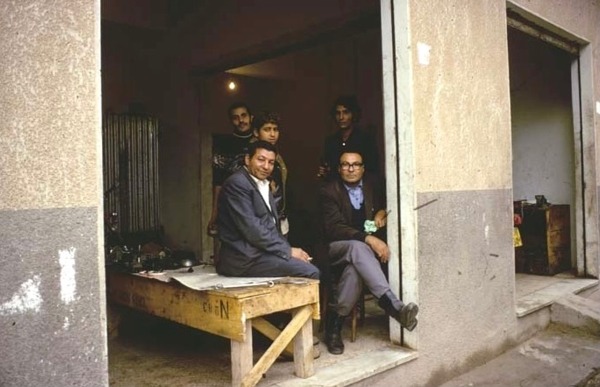

[I found a garage where I could work on the bike. I had never removed a cylinder head and pistons before, but I had a workshop manual. The two garagemen were no help with it but kept me in sandwiches and cigarettes for two days.]

Two days working on motor. Changed a piston. Sculpted the other. Garage life. Consider the number of old Citroens running around Alexandria. Compared with the European view that Arabs have no idea about maintenance. Obviously the truth lies elsewhere. Consider also the things that have not happened to me. I have not been robbed, solicited, harassed or treated as a Martian. On the contrary, from Tunis to Alex I have been fêted. Why? Clearly I stand in a different relationship to them. Monsieur Pacaud [a distinguished Frenchman also staying at the Normandie] would have it that the Egyptian makes no connection between his financial and personal relationships.

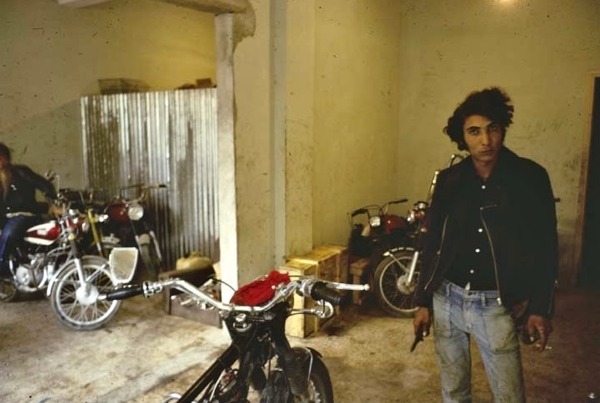

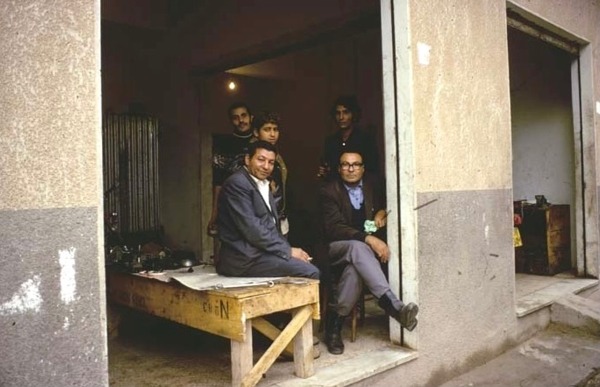

My helpers at the garage; near the railway station in Alexandria

Thus, at the garage we haggled over 5 piastres, yet I received much more than that in value. Sandwiches, tea and coffee were brought in impressive quantities. Cigarettes, which are a piastre each, donated freely. The first garage man says he has ten children, earns £E 7.50 a month (well, even if it’s more than that ten times the amount leaves him poor.)

Next week: My arrests

We left our hero (that’s me) stewing in Benghazi, hoping to get help. My visa forbids me to enter Egypt overland. Egypt is at war with Israel. After waiting uselessly for some news from the Sunday Times, my sponsor, I decide I might as well try anyway. Meanwhile I know that between Benghazi and the frontier are famous Roman ruins, not to be missed. These are the notes exactly as I wrote them.

November 5th, leaving Benghazi for the frontier

Kerim’s counsel – visit Cyrene and Appolonius on the way back.

Egyptian consul: “It is absolutely impossible for you to go through to Cairo.” Everybody else more or less emphatically agrees, although when they see I’m determined they say “maybe since you’re journalist”, and so on.

For myself I treat my visit to the frontier as an excursion and set out convinced that I shall return in four or five days to collect the papers now on their way from London, and to put myself and my bike on the plane to Cairo for about $60. I have found this cheaper than road transport for the bike (lowest quote £53) and although a boat would be cheaper there is none till the 20th – in two weeks’ time.

So off to Derna at 2pm. Lose my way slightly and detour by airport, emerging onto main road where the police checkpoint has massive queue of travellers in taxis. But I slip past unnoticed. Travelling East the fez gives way to turban, the women’s white cloak to the check pattern blue and red. Road good but uneventful. Even Michelin green bit is only an average road in the hills of Provence, but rising inland the air becomes quite cold. (although only 1000ft up, at most) and land much richer in vegetation and farming. Building projects, new houses the ‘new town’ with the mosque and grain silo

Realise I must have missed Derna road – and now on the road to El Beida, which means taking the antiquities in now rather than on the way back. But first nightfall intervenes. Find shallow dip between scrub wooded hills, where patch of grass has been cleared and levelled for my particular use by an ally.

Set up tent. Build fire. Cook Bulgarian mixed veg and peppers with corned beef. Coffee. Very good. Use battery/recorder device. Works well. 8.30 pm. No more distractions. Go to bed. Hear distant male voice, wandering past, coming to me from all directions, talking to dog, which yelps obediently. Can’t help a mounting sense of anxiety. And when the voice breaks into a lusty song I scramble into my trousers, shirt, sweater, jacket, boots and light a cigarette, and advance to confront the enemy. Amazed to find a flock of about fifty sheep gathered by roadside, (hundred yards away). In the middle, two cloaked, turbaned figures; Bright moon gives their clothes a rich appearance. (Next day I see it is only sacking.) We exchange greetings – try to converse but fail. I return to tent and sleep calmly, like one of their sheep. Awake to find them gathered about me. Gazing at the paraphernalia assembled (and am now packing) to pass a night which they endured with such simplicity.

[Although I am not religious, I was aware that this part of the world, called Cyrenaica, had an important part to play in the bible story, and I was powerfully affected by the biblical imagery conjured up in moonlight by noble-seeming shepherds in shining raiment ”watching their flocks by night.” Even more so next morning when, without the trick of moonlight their “raiment” was reduced to sackcloth, their turbans to rags, and they to poor, shivering peasants.]

It is freezing. Dew turned to ice. Fingers numb. Tent soaking wet. Pack and leave.

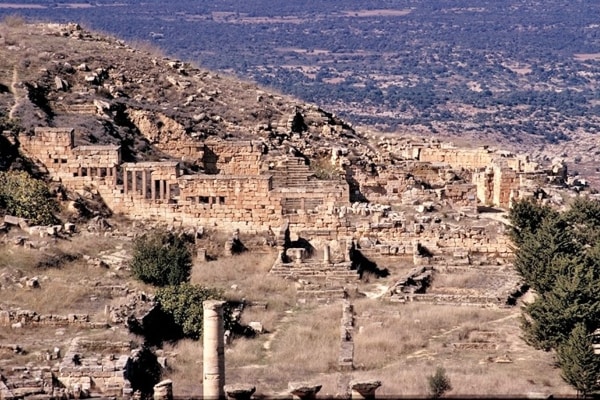

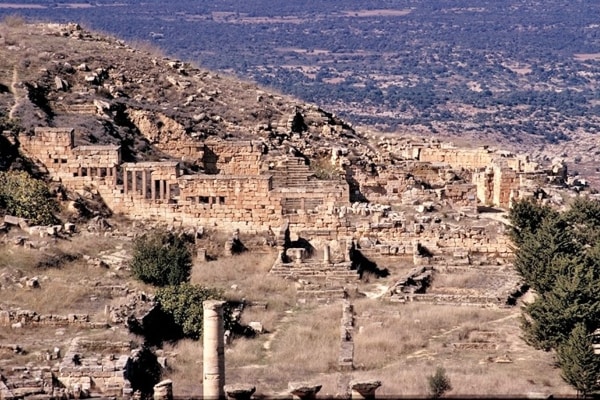

To Shahat, which is Cyrene. Ruins. Pictures.

[I was totally unprepared for what I found. A huge city of Roman ruins, totally deserted but for one Englishman, a French commercial traveller, and a minimal hotel staff.]

Frenchman at Tourist Hotel. Again, that curious French logic which somehow devalues the Arab quality while paying lip service to it. But good company.

(Jacques Puistienne, African Sales Director, Rhone-Poulenc-Textile, 5 Avenue Percier, 75. Paris 8e. 256 75 75)

Also, English ex-soldier, now wireless/radar installation engineer, living in chalet at hotel. Plastic on horns [???] British bring in brew-it-yourself beer. Says Libyans can’t cope with their technology. Mental age of fourteen.

Party of [Libyan] Air Force bigwigs arrive on guided tour accompanied by Air Force photographer with flash. Very American. After lunch they sweep in and out of Cyrene in ten minutes.

Englishman: “Border is military zone. Itchy trigger fingers. They shoot first then ask. One more Sunday Times man gone.”

All the world loves a lurid tale.

[I leave in the afternoon for Tobruk]

On past Apollonius, and the rugged coast road (the old Italian road) where again the sun catches me. Tent. Mosquitoes this time. Net works well – one bite. Stay up longer this time. Night warm. Sleep well. Morning dry. No condensation. Leave at 8 am. Derna. Tobruk. Hot sun. Meet Noel Moloney in road. Teaches at Oil (‘Isle’) Institute. Invited to tea. Stay for lunch. Wine. Wife Italian. Giuseppina. She hates Arabs. He says they’re childish. Earns £500 a month. 60% take abroad. Buying flat in Ancona. Another in Rome, and farmhouse in Ireland. Says the Libyans regard foreigners as “exploiters.” Has little affection for them. Remarks that after a while the students and staff at institute seem to have fondness for him.

Small children can’t play with Arabs because of skin diseases. [says the wife]

I become increasingly impressed by the difference between my experiences and those of other Europeans. “It wouldn’t be so bad if they didn’t treat us like Martians in the street.” Says Libyans under-use him. Works less than six months in the year (but paid full time.)

They invite me to sleep on my way back. [I am totally convinced they won’t let me into Egypt.]

At 3pm I set off for the frontier. 75 miles. 65 minutes. Convinced I can’t hope to pass but can’t resist the fantasy that I might. Arrive before sunset at Libyan police post. They take my currency exchange form. Why? They show no surprise at my passport. Obviously, they are indulging me in my little escapade. I humour their indulgence. I drive on, waiting for the man who says “No.” Have rehearsed all sorts of speeches about the meaning of war, the importance of adventure, the Arab cause, etc. Come to row of mobile site offices and barricade. More Libyans, but this time they stamp my passport. Now it’s serious because I’m not 100% sure that when Egypt sends me back, Libya will take me. Ridiculous. They wave me through. What, all the way? Yes. I drive into the main customs area, and with delightful innocence plough past the massed taxis, turbans, and mountains of carpet in plastic bags. Eventually I’m hauled back to the “Captain” who presides at a desk on a rostrum.

There, a roly-poly man, unshaven, moustache, takes me personally under his wing. Jumps all queues, gives me a glass of tea. Then:

(1) Man reads my UAR visa, several times looks at “No Entry” qualification. “Access to the UAR via the coast of N.Africa and Salloum is not permitted.” But seems to see nothing there of interest. Takes me to –

(2) Where, with a semi-literate they fill in a Roneo’d form. Great problem with XRW964M. Then give me the paper. I stuff it in with the carnet. Then –

(3) And (4) is another flurry of papers, given and exchanged. I no longer have any idea which are Egyptian, which Libyan, but keeping track is full time as Roly-poly beckons me on. At one point I lose sight of the first paper, something to do with police. “Is it important,” asks Roly-poly. “It isn’t. Never mind.” I give way, knowing I shouldn’t. Change money at (5), pay for licensing bike at (6). Back to (3) for argument about carnet. Then at (7) Libyans discharge it. to (8) where a police officer behind a row of ledgers so thumbed as to be eroded like old stone bannisters, says he’ll give me three months and hands me two heavy steel number plates. Bemused, I totter off with my load.

“That’s all,” says Roly-Poly. “Now, can I help you in any other way?” I don’t know what to do. Fumble towards my pocket, then decide against it. He looks corrupt, but that’s as likely to be my prejudice. Why assume it? He seems happy enough when I thank him and turn away.

Earlier, he asked, urgently, “Did you thank him?” referring to the captain. Puzzled, I replied “I always thank everyone.” He laughs loudly, but I’m no wiser. Did he mean bribe, reward? Meanwhile I’ve found that first cryptic form again, and stuff it away with all the others. There is no room for passport and wallet in the tank bag. I lay them over big gloves in the rt-hand pannier. Lock up and leave. The impossible has happened. I’m in Egypt.

Next week: The rocky road to Alexandria.

A missing chapter. For those of you bothering to follow this series of notes chronologically I have to confess that I mistakenly left out a section of notes about the ferry from Palermo to Tunis. Because I think it was significant and reads rather well, I’m going to interrupt the story and tell it here:

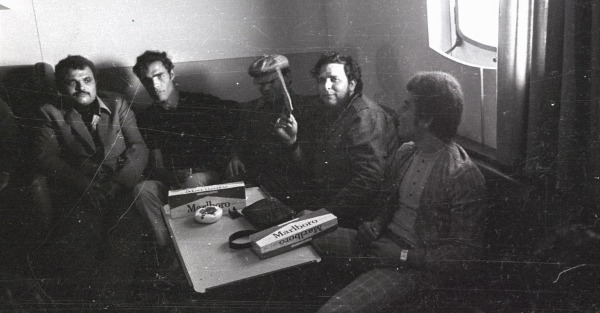

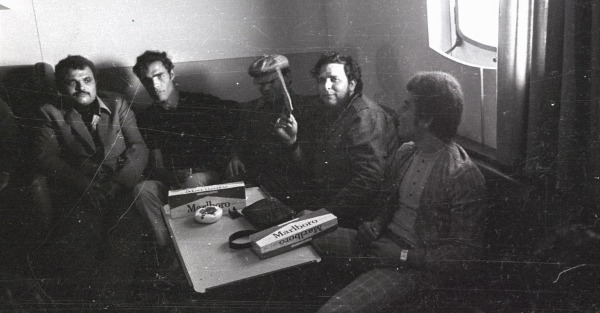

On the ship between Palermo and Tunis, the second class lounge was dominated by two personalities: the Italian barman and an itinerant Tunisian visiting home from the great casual labour markets of Northern Europe. They were at opposite poles of human conduct.

The boat left at 9.30 – a fine looking, modern boat, with drive on facilities, called “Pascoli.” On the deck I met, briefly, two somewhat effete Englishmen with a Renault, driving back to their home in Tangier. I still seemed a long way from the kind of Africa I was expecting. Then I saw the Tunisian Hassen from the market yesterday, and with him was the man who became the pivot of the ship’s life for most of the morning.

He was chubby, Castro-bearded in a green tunic (US style). Shock of black hair at the top, pale skin wrinkled by much facial work. Coconut shaped head. About 30 years old. Started by being merely noisy.

“Ah you, vous, wass machen, sprechen Deutsch. Ich auch. Scheisse.” Burst of Arabic. “Ich bin Hamburg. . . . “ and so on. Then he started singing. I just thought he was a disagreeable oaf, and went down to the lounge for a beer, where the Italian barman held sway. He represented all that was petty and corrupt. He treated the lounge and its occupants, mostly Tunisian Arabs, as his private colony. His strutting and posturing were unforgettable. The bar was his seat of administration where he granted or withheld service as capriciously as any despot. No, withheld is too mild. Refused, volubly, rudely, with accompanying gestures. Every now and again he would fly into a tantrum about the television set tuned, naturally enough, to a Tunisian program and insist on switching to an Italian football match, although the picture was scarcely visible, the sound was no more than a roar of static, and he himself never once looked at the screen. When his bumptious little body, with its prematurely pregnant belly slung over the Italian sailor’s sash, came round on a tour of inspection, passengers dozing iin their seats with outstretched legs had their feet roughly kicked out of the way, while his equally offensive sport was to fling empty bottles into a large container where they fell with a regular shattering crash. It was truly breath-taking to see one man seize upon his environment which theoretically belonged not to him but his customers, and make of it an instrument for the complete expression of his selfish nature while the rest of us submitted in our various ways, resigned, resentful, or merely numbed.

He represented in my eyes all that is brutal, greedy and corrupt in human behavior, and he was a powerful influence in stimulating my sympathy for the Arabs. Short of violence it was obvious that the man could not be stopped.

The poet is waving a paper in front of Mohamed’s face

The singing buffoon came in a little later, when it started to rain outside. He sat at the far end of the lounge still chanting and smiling as though at some Sufi vision. In the confined space the songs were much clearer. Hassen said they were nonsense about girls and love, and he was apparently making them up as he went, but at least he offered an alternative kind of vitality to the terrible malignant power of the barman.

The Arabs nearest him began tapping and clapping along, and others drifted closer, but he continued for a while as though he were unaware of any of us, playing the fool for another audience that only he could see. The barman was noticeably annoyed and the tempo of his outrages increased, but although he still commanded two thirds of the saloon he did not meddle with the singer, whose territory was growing. I sat for a while on the border line of their two spheres of influence, and it was like looking out on two different worlds. To my left, shouting, hostility, the smashing of bottles and, from the TV, the gibbering howl of the ether. To my right, singing, laughter and a beat that was beginning to reach into me. Hassen and I moved across to the right.

The singer judged this the moment to come out of his private retreat and began to respond to his followers. I could not imagine how I had ever thought him distasteful. At worst he was a simple clown, but his power now seemed to grow as the barman’s dwindled. He interrupted his buffoonery with poetry, and Hassen told me it was original and good. The same thumb and forefinger placed the words in the air with a precision and meaning that I felt I could understand, though I spoke no Arabic. The songs also became longer, more lyrical. Slowly, over a period of several hours, the pitch of his performance built up. The barman by now was utterly effaced, the TV could no longer be heard. Everyone in the saloon was with the singer, his to a man, and yet he still seemed strangely detached from us, not feeding at all on our adulation in the manner of a Western “star.” Nor was there ever an attempt by anyone to compete with him. He remained the focus of energy for the rest of the crossing.

Towards the end he moved from songs and poetry to oratory. It was a long speech, and if the rhythms were anything to go by, it was in the Arab equivalent of blank verse. His voice now was very muscular and gritty. The harsh, hard-nosed syllables flew out in formation and beat on my ear. His audience replied with moans and cries of agreement. I imagined the voice amplified a thousand times, a hundred thousand times, from loudspeakers on all the minarets of Islam.

The sounds conjured up an atmosphere of great ferocity, yet the sense of the speech, it turned out, was moderate. It had to do with peace and war in the Middle East. It praised the moderate statesmanship of Bourguiba, and poured scorn on the troublemakers who would fight, like Qaddafi of Libya, to the last Egyptian. Hassen said it was good sense, realistic and very poetic.

The train driver from Sousse translated and gave his view.

“At first I thought he was a fool. But now what he says is really impressive. It is realistic and good sense and very poetic.”

It was well after dark when the ship arrived in Tunis. By then I had made another friend, Mohamad, a young Tunisian who was one of the singer’s most enthusiastic accompanists. He was more stylishly dressed than most, with a jazzy peaked cap on, which he never removed. His nickname, loosely translated from Arabic, meant “The Swell.” He asked me where I was going to stay in Tunis, and I said I had no idea.

“Then you will stay with me. My family will be very honored. You will have everything we can offer. We will be extremely proud to have such a famous man in our house and our friendship will last forever. I have a dark skin but my soul is white as a lily. You will be safe and well in my house.”

Before leaving the ship I happened to notice the barman. He seemed a rather insignificant person, cleaning up after us, hardly worth bothering with.

The poet is in the middle. Well, I never claimed to be a photographer.

On the road to Benghazi.

Wednesday, October 31st, Marsa Bregha

Oil refinery and tankers. Aircraft parked in the desert. No houses. Eerie. On to Benghazi. Run dry within sight of it. Fortuitous. Two good young men. Give me petrol. Take me into Benghazi. Buy me a tankful!! Take me for coffee. Help look for elusive Sabecol. [The Sunday Times had a point of contact in a business called Sabecol.] Help me find hotel. Offer to help with phone call – through brother in PTT. [Post office] Lend me a pound. Stupendous hospitality and generosity.

Meet man with garage in the same road. Freedom of the house. Eat beans, tripe, peppers. 10 piastres. Walk round Benghazi and fall in love with it. Squares with parks and fountains. Women in streets. Shops and arcades. Fascinating markets. Poles away from Tripoli. Shoes at six or seven pounds. Watches everywhere. Backscratcher for Jo. But insides are all ugly. Thought is beginning to form. Beauty at price of personal ugliness. Kindness flourishes on barren soil. Streets are paved with potholes. As though a tank regiment had just fought its way through.

Wednesday 31st

I am living in a community virtually created for me. The hotel. Opposite the small restaurant, white tiles, oil cloth, odd smell but you get used to it. Clean, cheap. Just 30 yards down, the motorcycle workshop, put entirely at my disposal by the owner, Kerim Ali.

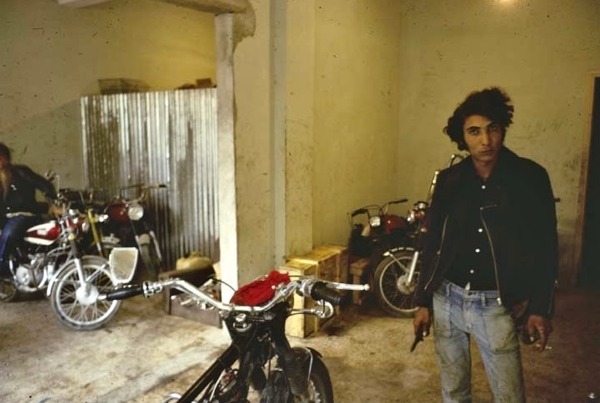

Kerim Ali and his workshop. Tremendous help and enthusiasm.

And opposite him an amazing scrapyard come general engineering shop run by Mustafa, a skilled engineer where I can get anything made, welded, etc. But the mysterious Sabecol still eludes me. Kerim has been given six different telephone numbers. Every time he rings directory, another number. He grins disarmingly. Tomorrow, he says, we will drive there. Sa’ad passes by and starts working with me on the Triumph. I clean it, reset timing, tappets, clean out carb. Change chain, change oil, change plugs. Tomorrow grease and oiling.

Sa’ad worked on the bike with me, and invited me to his home.

Walk around with Sa’ad. Everything stops at 9pm. Except the café on the sea front. Veery pleasant though. Gold market. Fishing with dynamite. Another tedious banking scene. Dollar down to 2.50 to pound. Bad business. Surfeit of one dollar bills.

Thursday November 1st

Another day. But Sabecol has been penetrated. The omnipotent Kerim drives me out of city on Tripoli road where he says all big businesses have moved. There is very little “traffic” (business) in Libya these days, he says. The people have money, but they keep it. Afraid to invest. Sabecol is an empty space.. Used to do British cars and bikes – now only get spare parts. Letters there from ST. Another, to P.O.Box 217, has got away. Back to Kerim’s shop. Sa’ad arrives. More work on bike, fixing the recorder input lead. Talk to Mustafa the welder. Specialises in cast iron and aluminium alloy welding. Oldest welder in Cyrenaica. Amazing workshop – a jungle of scrap metal. Rusted corrugated iron overhead. He limps. Has a soft, fastidious expression.

On the way to Sa’ad’s home I disgraced myself in a pool of wet clay.

I drove Sa’ad to his house across a wasteland of rubbish, craters. Old World War II US airfield, with £25 million university rising out of it. Around it – then swoosh, squelch – into wet mud, clay – over we go. Come up like figures ready for firing. Pic of bike. And all that time spent cleaning it. Cameras encrusted. So Sa’ad drives while I palpitate on back. No harm. Very funny incident. But I hope I see it next time if I’m going faster.

Two pictures of Sa’ad’s home.

Is Sa’ad on his mobile phone?

Sa’ad’s home a long, square plot by the beach. Those ‘date’ palms, are either unripe dates or something similar. They have sheep in a pen built of old doors, planks, windows. Profusion of parts. Vegetables, onions, cabbage, tomatoes (on ground) Donkey. Dogs ( 3 ) Cat and kittens and endless brothers. Also pigeons, small turkeys – or guinea fowl? All within yards of the beach. A great stack of sandstone blocks (inhabited by a rabbit) waits to be added to the house (hewn from that same quarry). Sa’ad has two shacks of plank strewn with motorcycle parts and machines in rusty dilapidation. A Triumph Trophy, a Guzzi, a Yamaha. Advertisements for cars, motorcycles, and a British shower manufacturer from Birmingham contributes his two pennorth of titillation with banal lady under shower with nipples showing. The shack nearest the shore is on stilts and has a Cannery Row feeling about it.

You drive fifty miles of barren road and ee a triumphal arc across the road, usually sky blue and apparently made of plywood and plaster board. At the foot of the arch is usually a policeman or a soldier, and often they will stop you for your papers. After this the road generally deteriorates and widens out to be about three times the width with rough asphalt or mud. Theen, on either side a row of single-storey, open fronted spaces of brick and plaster, used variously as café, a general store, living rooms, a garage, etc. Because no particular style has evolved to differentiate between premises for, say, a builder or an ironmonger, my western eye has difficulty seeing through the general jumble. On either side a row of pumps, sometimes new, sometimes rusted. It’s hard to tell which are working. They all carry the sign of the government oil company although I gather they are serviced, as before, by different companies, Shell, Esso, etc. But you don’t know or care what you’re getting since its half the British price.

Parked by the pumps are likely to be: A Peugeot 404 estate taxi, nose and tail painted white, mid-section black with a group of sombre men packed inside wrapped in white shawls and topped with fezzes, often clasping cushions or pillows in plastic bags; a row of buses containing a mixed cargo of soldiers and civilians and driven by either; any sort of private car as long as it’s German, French, , Italian or Japanese; a Datsun or Toyota pick-up truck. Buses and most taxis have tarpaulin bundles of luggage on top. In October, November the area is a sea of mud.

I have never seen an Arab manifest impatience or throw rank (except within the family).

Monday November 5th

And I have been here too long. Or rather I have been here long enough to feel time weigh on me. Clearly, I am impatient to get on, frustrated by the delays and still uncertain about a plan to get across, so I feel the time pass. But for the ordinary young man in Benghazi time is scarcely less of a burden. There seems to be little else to do here but work or speculate. The streets are crowded in the evenings by groups of men talking. There would seem to be literally nothing for them to do except go to the cinema. Some go every night. The arrival of a new film is a major event. Much of the audience is acquainted, and they react to breaks in the reel with esprit de corps – like an army audience.

Much lip service is paid to the evils of war but the only convincing sentiments are those deploring its economic effect. Kerim says the price of timber has gone up from £30 to £50 per cubic metre. I don’t think anyone actually wants to fight, but many are impressed by the idea of fighting. Violent films are popular, and there seems to be a karate craze on here. Twice I’ve seen a youth in the street play at a karate blow and it’s been mentioned casually several times. Benghazi itself was designed for more frivolous times. It has several squares with palm trees and fountains, formally laid out with pools geometrically pattered among tiled areas and flower beds. Sharia (road) Omar Mukhtar has arcades running its full length – modern, including the post office, giving way to 19th century. Virtually every ground floor opening onto most streets is a store of some kind. And invariably steel rolling shutters come clattering down at 9pm giving the town a bleak, dead look. Road works everywhere, pumps ins continuous operation provide Benghazi its characteristic background noise, like the cicadas in other places. Yet in spite of the bombed sites (are they really still from the war?) and the shattered roads, the city promises a sophistication and variety which it cannot deliver.

Undoubtedly the current regime has flushed out many babies with the bathwater, filthy as they may have been. With alcohol and tourism gone there are no clubs, no luxury restaurants. The West is represented only by its hardware. A parade of watches, transistors, cars, domestic appliances. No live music at all, except for religious festivals and marriages. Apparently, no theatre, and little demand for it. A ‘bloc’ mentality, faintly reminiscent of pre-war Germany, but without the economic hardship. Libyans have money. The State shares out its oil income with allowances. £5 a month for every child. A £40 pound allowance for married men. £20 for single men. Young people seem healthy, bursting with vitality. Slim. None of that Western obesity. But all heavy smokers. Older generation frequently bow-legged – some squints. Older women all seem stunted and prematurely aged under their red or blue checked burkas. [I don’t explain how I saw beneath them!]

Here at least (unlike Tripoli) girls in Western trouser suits are seen in the streets going to and from work (or school). The atmosphere is less repressive. There are skins of every shade, from pale Libyan through brown Egyptian, to coal black Sudanese. The Egyptians have been brought in as cheap labour and are becoming an embarrassment, I’m told.

As well as selling goodies, there is a disproportionate number of shops dealing in paint, tools and electrical fittings and materials indicating a great preoccupation with house renovation. Police and soldiers everywhere, but not in an intimidating way, except to the paranoid foreigner who feels suspicious eyes upon him. It is considered unwise to take photographs and nobody uses cameras. Arabs are said not to like having their pictures taken. I have always found the opposite to be true however and I think the camera-shy Arab is a myth in the city.

All in all, I feel this society is off balance, and that much of what is wrong in the Middle East may be the consequence. The spiritual life of Islam has no answers for a restless new urban class, yet they cling to it. I can’t honestly say I wish them the benefits of a Western cultural life, or that they should cease to observe the customs of hospitality which I have enjoyed to a surfeit. But there is tension, and loose energy that the pursuit of technology can only exacerbate.

Sa’ad’s brothers did the clean-up.