News from Ted

Chased out of Tunis by the police, and heading for Libya.

Tuesday 23rd October

Drive through Tunisia. Wet. Confusions at Sousse. Wrong name for the train conductor. On to Gabes. Hotel de la Poste. Letter to Peter. Right or wrong? Frenchman at Atlantic. Was there in war to put up radar station. Germans no good at electronics – except Siemens. Italians did nothing for the Libyans.

The coliseum at El Djem

Floods. Road cut behind me. Sousse. The Alaba? Hotel. All hawking and spitting. Good restaurant by the roundabout. Room was I dinar (£1) Remember how I was cornered with the bike in small gateway at back and forced to bargain for parking. I didn’t even know there were people sleeping under all that plastic at the back until next morning. I wonder whose lodging was more profitable – the man or the motorcycle?

Remains of a Roman aqueduct

[There are some days here I can’t account for, but I arrive eventually at the frontier with Libya. It’s not long since Colonel Gadaffi (or Quadaffi) seized power.]

Libya, Sunday 28th

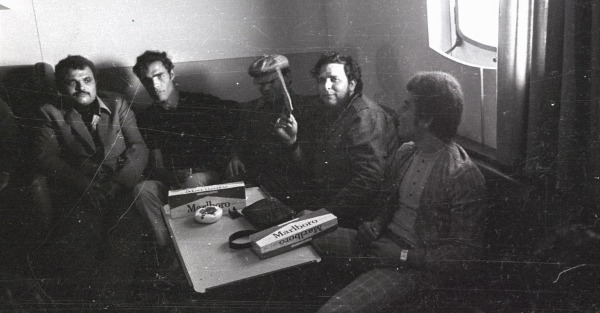

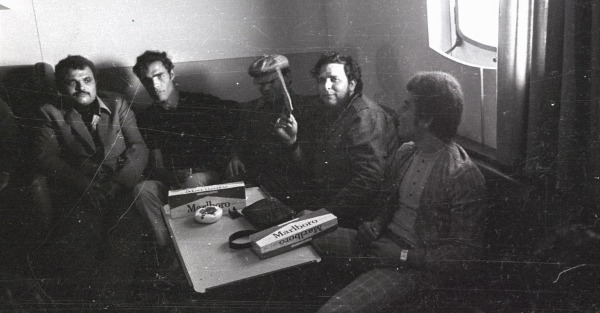

Police. Man with shotgun. Chief in his shiny Italian suit and suave grin, with carton of Marlborough under his arm. Customs man. Other man who came in to do police forms and passport.

“Helt?” he said. Oh, Health!

Sheets of Roneo’d forms in Arabic. No communication, but goodwill.

“Whisky?”

First taste of Libya, all Arabic. No alcohol. All fizzy water and Pepsi. Night on the dunes. Chakchowka [?] Coffee. Tent tied to bike. Lightening at sea. Then in morning, rain. Will bike fall through the tent? Will I be washed away? Frenzy of packing as huge black storm cloud piles up behind me. More sand than tent in the bag. But bike travels well over wet sand. Hooray for Avon tyres. But what hard work. And what did I lose in the process? Nothing, as it turns out.

On to Tripoli. Totally at sea with Arabic signs. Can’t distinguish one sign from another. Ask a driver for “hotel?”

“Follow me. I have time for you because I see you are lost.”

Customs took half my Libyan money. Hotel costs two and a half Libyan pounds – that’s over £3. Money is going at a rate. Meet Yorkshire engineer. Walk to the esplanade. Port full of ships.

“Been there for weeks. Port is too small. Can’t turn them round.”

Hotel full of roughneck Italians. Pipelaying gang reading comics. Not a woman in sight. In the street occasionally see bulky objects swathed in ‘Barka’, one eye showing. Mustn’t look at them. Who would want to? City looks full of bomb sites. Arrived at 11am. Spent most of the day sorting out mess from the night before. Into the shower with the tent, washing sand out. Dry it on balcony. Boots sodden.

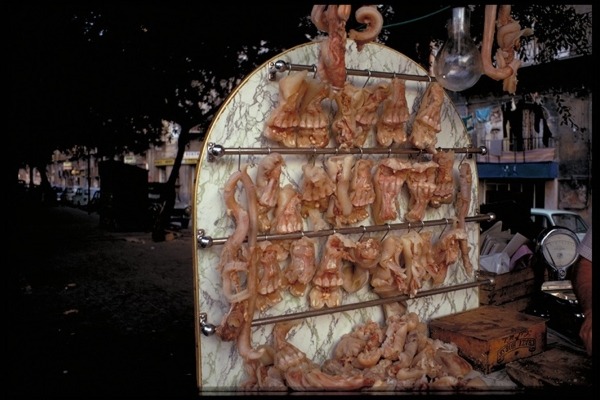

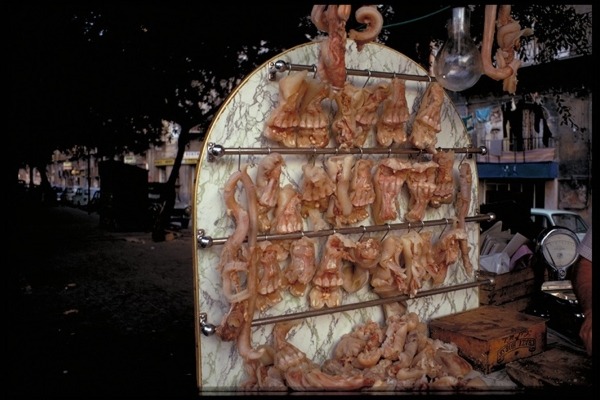

Don’t dry till next morning. But dubbin goes in well. Market is full of transistor gear. All looks like rubbish. In fact it’s all very rubbishy. Not a pretty object in sight.

Amin [Uganda president] is in Tripoli. Appears on television, like an ape-man.

In the morning, the bank. Soldier, shabby, hairy, with gun. Stout Arab is at the cashier. Behind cracked glass three men are all engaged in counting his money. He has brought a stack of notes over a foot high. And all in fives, tens and twenties. They count them again, and again. Holding bundle with one hand, flipping notes sideways with the other, looking around and smiling at friends, losing count and starting again. Twenty minutes goes by. Rain still bursts down sporadically.

Off at last. After eleven. The road to Benghazi. First, olive groves. Small trees. Then thousands of date palms. Dates light brown clusters at centre of palm – like dead leaves. Occasional camel. Settlements, earth confined by mud dykes. Wells of curious shape. Why the steps? Tried to ask the man here at hotel. Yes, he said, it’s like this. The road from here is good for 250km. Then there’s a very bad stretch of 250km !!!!???? Indeed. And what happened to my bed at 75 piastres? One Dinar it costs me for an army bed. But I digress. This is no tourist country. Why should I complain about it? That’s how it is.

The desert. Wow! Really desert. Out for ever. Cloud. Sun. Rain. Blue sky. All at once. For hundreds of miles around. I’ve never seen so much weather. Part of it’s dry. Groups of camels gather by the road. Frightened by noise, but shrubs grow greener at roadside. Pictures. Camels in haze of sand. On and on. Sand drifting across tarmac makes patterns like flames in fire.

First mechanical trouble. Throttle is stuck. Can hardly move it up. Won’t slide back. Have to cut off to slow down. Get to Ben-Gren way station.

First signs of trouble. Air filter inadequate.

Two Egyptian labourers help to move bike into shelter where I clean sand out of carburetor. This is going to happen again. Get a plate of spaghetti – young fellow, son of owner, speaks English. He gives me the food. Take pictures again. Also took pic earlier of – Septis Magna – was it?

Police stop me once. Go through my papers. No question of insurance, though. Drive on as sun dies behind me. Into the gates of hell. Huge storm blackens sky ahead. Seem to be always driving into the worst weather. Altogether this journey feels like that. Sort of apocalyptic. Like Frodo going to the dark country.

After the storm, road suddenly barred. Diversion points out into the desert. Can’t see a road. Decide to ignore sign. Tarmac continues, very broad, almost like an airstrip. Is it? Nearly at the end, car full of soldiers comes weaving past and stops me. Examine my passport upside down, very earnestly. But always with good humour. Police and soldiers shake your hand afterwards. Wish you well. On into the night. Feel good, alert. Ready to drive all night, but stop for petrol at Sirte, and soldier says I must go to police. Evidently, they don’t like people out at night. Have to stay at this hotel. Rambling building. Group of Arabs in fez and pyjamas sitting in one corner smoking and drinking tea. Those famous pyjamas. Desert dogs look white and handsome. Ground in Libya looks as though it’s had the top ripped off – like bottom of a disused quarry.

Sirte is a sea of wet sand. But everywhere among the broken buildings, the rubbish, the peasant shacks, are new cars gleaming. Black and white taxis drive up to the poorest buildings, rush up and down the highway – big Peugeots, Mercedes, Datsun trucks, Toyota rovers. And everyone seems to have a stack of those big banknotes, to make me feel poor, underprivileged like a newly arrived Pakistani.

In this weather the tent is almost impossible to use. Hotels break me. Only petrol is cheap, thank God.

Oh yes. Big tents in the desert, usually near a village. Like marquees.

Lousy desert picture, but it’s all I’ve got.

Tuesday, October 30th

Left Sirte at dawn. Clerk sleeping in his clothes by the door, wrapped in a sheet with light on, his white fez by his couch. Arabs by the car-load continuing their journey. Rain goes on. Very heavy for three hours. Can’t believe the bike won’t stop. God bless Triumph, and Avon – and Lucas. Stop for petrol at small place before Sidr. Cup of mint tea, packet of sweet rolls. Bartender takes 10 p. Must have cost more. Had two shaky moments on mud ridges dried hard and then wetted down. Was into the second before I realised what the first had been.

Absolutely soaked. Boots squelching. Crutch sopping. Then, at 10am, after 150 miles head down on tank, like a bullet at 70mph through downpour comes the light. This desert is not the desert of BOP, of Khartoum and Lawrence. This is a primaeval swamp and camels look like prehistoric monsters. Rivers gushing along the side of the road. More permanently garnished with shredded tyres and cautionary wrecks – road safety sculptures of cars frozen and rusting in the posture of collision. A deliberate warning? Or simply neglect.

The sky clears as I drive out from under the roof of raincloud. Stop. Walk in the desert. Picture of bike draped in clothing. Then on in sunshine. 100 miles from Benghazi, make coffee, eat sardines within 100 yards of tented encampment. But nobody approaches.

Next week: To Benghazi

I took the ferry from Palermo to Tunis.

Sunday, October 20th

For some days I’ve been travelling on the brink of Africa. From London, perhaps, Tunisia seems no great distance, just a package flight away. For myself I can only tell you that after 2000 miles travelling towards this immense continent, speculating on what lies ahead, I feel a very long way from home and, in quiet moments, alone as though I were about to step off the edge of the world.

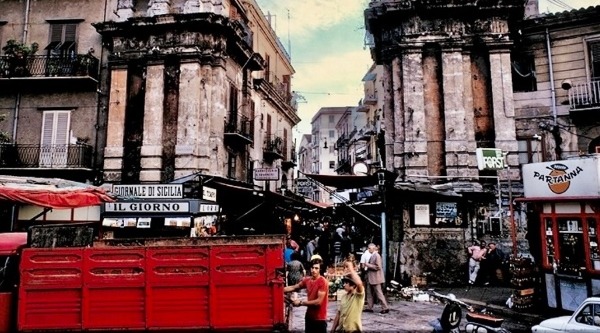

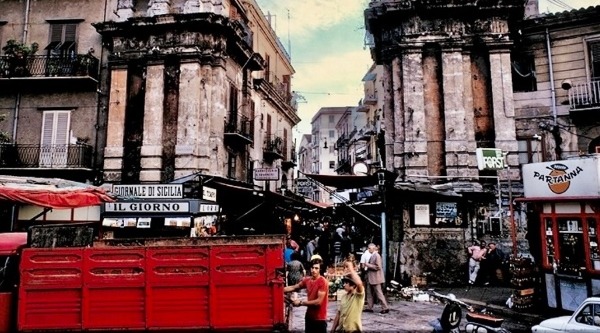

Goodbye Palermo

The boat left at 9.30 – a fine looking, modern boat, with drive on facilities, called “Pascoli.” On the deck met two somewhat effete Englishmen with a Renault, driving back to their home in Tangier. I still seemed a long way from the kind of Africa I was expecting. On the boat, in the plastic lounge, was robbed for a beer. I met the Tunisian from the market yesterday, but he failed to make much impression because with him was the man who became the pivot of the ship’s life for most of the morning.

He was chubby, Castro-bearded in a green tunic (US style). Shock of black hair at the top, pale skin wrinkled by much facial work. Coconut shaped head. About 30 years old. Started by being merely noisy.

The poet is waving a paper in front of Mohamed’s face

“Ah you, vous, wass machen, sprechen Deutsch. Ich auch. Scheisse.” Burst of Arabic. “Ich bin Hamburg. . . . “ and so on. Then he started singing. Gradually he drew his audience around him. Singing and clapping. Soon he began to formalise his act. And from buffoonery he moved to love poetry and then an extraordinary declaration on behalf of Bourguiba. Much of this I have on tape. The train driver from Sousse translated and gave his view.

“At first I thought he was a fool. But now what he says is really impressive. It is realistic and good sense and very poetic.” Much of this is on tape and performer’s address is in the book. Took B&W pics but quite dark and will need pushing through.

[I was still planning to send tapes back to the London radio station.]

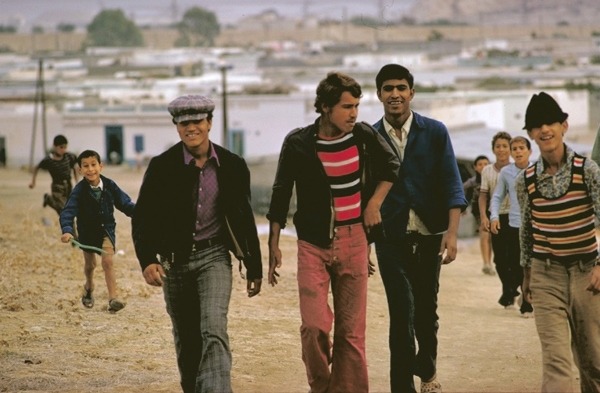

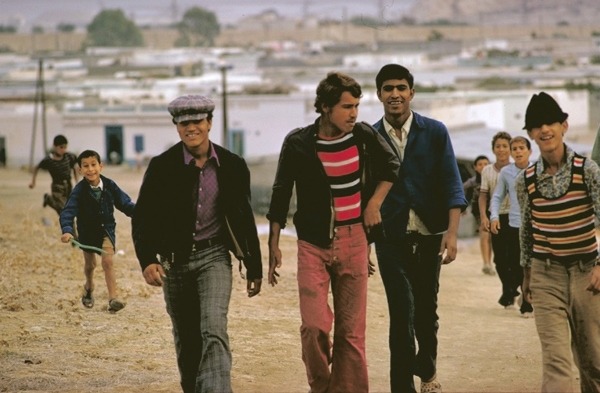

Singing along was a young handsome Arab with a peaked cap and smart jacket. He also was very friendly and although his French was worse than the other’s he persisted and invited me to his house. I followed the taxi round Tunis and then through an open dark area [night was already falling] to the Cité Nouvelle el Kabbaria. Blocks of plastered brick, 1 storey high. No window. Set down in rectangular arrangement on stony ground.

Mohamed (left) and friends

In No27 Rue 10083 lived Mohamed’s family. There are 9 altogether but only five of them live here. Two small kids and parents. Father, red fez, trousers and shirt, runs a tabac. So he has a room opens onto street, with a counter. His tabac is lit by a Japanese paraffin lamp. Mother smaller, and similar to Algerian ladies in Lodève [my nearest market town in France]. Five children. One other daughter married and pregnant. One youngest girl and three boys. The two small ones are barefoot, very appealing, curious, active. At night, with light and shade so mixed, it’s hard to see the building as a whole but in the morning I see.

In the back room, which is Mohamad’s, a sumptuous looking bed draped with a cotton pile rug in shiny floral pattern. This seems to be the only bed in the house and is offered to me. I am not quite able to subdue my imagination which still suggests that I have fallen into a cunning trap, partly because I’m set down on a chair in the bedroom while whispered conference in Arabic outside. But commonsense tells me this isn’t so. Shortly, I get up and walk into the courtyard, but some residue of suspicion must have shown in my movement or expression. Mohamed said I could come and watch the motorbike if I wanted, but it was all right. Slightly shamed I returned into the room (which was never more than a few feet away) to find that a dish had been laid there with bread. Two small lamb chops in heavily spiced hot sauce with peas and a pepper. No cutlery. Got my hands messy trying to scoop up the sauce and peas. Couldn’t finish it – too hot. Felt bad about that too.

Wanted to let M sleep in his bed. “Whether you sleep in it or I it’s the same thing. If you sleep in it, it is as if I were sleeping in it.” The Arab formula was not florid lip service to some tradition. It was real and meant. No doubt. Although the bed was a doubtful privilege. Couldn’t sleep for ages, with tickles, particularly on my hand. Lay on the rug with a sheet to wrap around. In morning enormous numb swellings on my left face, neck and right hand. All out of the sheet. Felt as though some fearful African leprosy had struck me down already. Of course they must be bed bugs. But WHAT bugs!

In the night someone processed in the street beating a soft drum at slow march, missing an occasional beat. He was announcing the time to eat for Ramadan – before the light at 4.35 am. For these are the last five days of Ramadan. And Tunis has an Italian fairground to celebrate it. No eating, drinking during daylight.

Remark by Mohamed, “Mon coeur est blanc” – “My heart is white.”

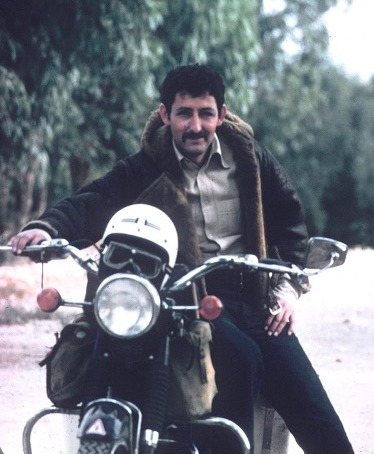

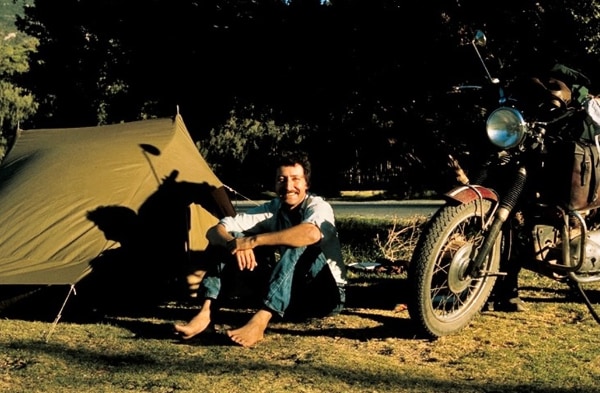

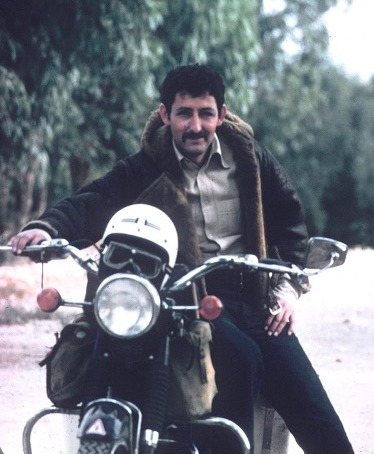

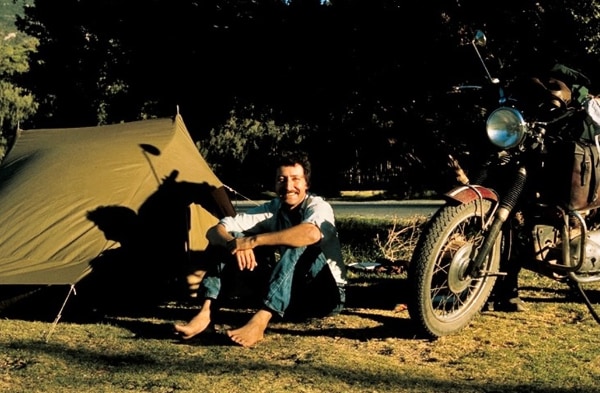

How I looked then

Monday October 22nd

Went to the ‘forest’ – a sparsely wooded slope leading to a beach where “all of Kabaria” sits in the summer “to admire the view and the trees and the flowers” with Mohamed’s friends and brother. We took pictures of all of them sitting on the bike in turn. These I hope still to have, including a “Magnificent Seven” pic of them coming up over a hill.

No question, M is impatient with pix in which he doesn’t figure and has a star’s attitude to photography presenting his best profile (one cheek is scarred by eczema or acne). In a sultry mood.

In the evening, I took him to Tunis with some clothes for another sister, and her husband who mends watches. More appealing children.

We’re invited to lunch by M’s brother-in-law. He has a job, and has a prosperous look, confident, etc. Newly married, wife is pregnant. Sweet in pink gown, tight round her belly and behind. She has cooked some of the food that M bought at the market. Olives, pickled vegetables, salad – crinkly kind – grenades. No plastic. Thick paper wrapping.

[They took me to visit the brother-in-law’s father, a traditional country “paysan.”]

The oven where they bake their unleavened bread

The brother-in-law’s father’s homestead. The bread oven, cow and calf. Beehive. Cactus hedges. Story of Jewess who has children by the man who killed her husband. “Beschwaya, beschwaya, wait and see.” [Slowly, slowly. She teaches her children to kill him.]

“Jews smell,” he says. Clean area. Charcoal brazier. Couscous with chicken. Powerful tea. Old man’s feet. Face. On bed smoking. Wife always behind me. Crouching over fire. Bread and honey. Leave after dark.

The day at Libyan embassy. The “jailor” in fez. People all living in one room. The desk clerk at Hotel Africa. “Arabs don’t know how to make politics. Here’s the round table. Here’s a general, a king, a dictator, a democratic president. They never agree. So they can never bring force to bear. Always arguing.”

Tuesday 23rd Leaving El Kabaria

The final incident. Pied piper leads huge hoard of children and people. M swinging the camera. Police. Film exposed. Humiliation. Departure. What did the police tell him?

[I had no choice but to leave in style, with half the village trailing behind me, but two ugly-looking plain-clothes policemen came to break it up – threaten the people, seize my camera and open it to expose the film, then accuse me of whipping up a mob for my own dastardly purposes. Tell me to get lost. The following picture of Mohamed’s father in his courtyard just survived.]

If you read last week’s notes about Zanfini, you would probably like to know what became of him and his project. I returned to Roggiano in 2001 and wrote about it in Dreaming of Jupiter. I have reproduced some of that at the end of this week’s notes. For more you might like to buy the book.

Friday October 19th , Leaving Roggiano

Now just a matter of making distance to get to Palermo. Have only a sketchy idea of distances in Sicily. Think it’s pretty small. Partly the effect of Mercator’s projection, but mainly through insular whim concerning islands.

Ferry crossed from Reggio to Messina at 3 –3.30 pm. Cost 700 Lire (150 for person) Carries trains and cars. Rails on wood warped into barrel-shaped sections between rails. At other end, straight on to promising Autostrada missing Messina altogether. In the event it was 150 miles of which perhaps 25 were motorway, the rest sinuous coast road with patches of “original” Italian road surfaces. One and a half hours of daylight driving, three hours in dark following a car or a truck. Into Palermo itself, a half mile of cobbles. Arrive at 8pm, very far gone.

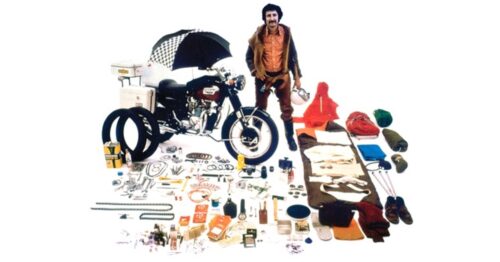

Mentally, when I get off the bike after a long ride, although capable of thought, I feel almost incapable of initiative. I want to reach immediately for the nearest source of rest, food and security. And this is where the act of motorcycling can impose an unusual perspective on life. Can make a prince feel like a peasant.

First of all, it is almost impossible to ride hundreds of miles with traffic without getting filthy and feeling it. Second, and I speak now about cities, you can’t leave the bike. Assembled on it is your universe, a natural target for thievery. Like a Christmas tree it glitters attractively and has presents tied all over it. You and it must be inseparable. You can’t lock up your car and melt into the crowd. You must attract the crowd, and the crowd becomes your enemy and your salvation. Because somewhere among the curious children and adults is someone who will help. But who to trust? How to convey your meaning with few words in common? All these things require patience, reserves of goodwill and imagination, which are precisely the qualities you’re least able to call upon. In summoning them up you dig into your own personality and painfully a sort of truth emerges which represents you, not as you would like to be seen, not as you think you ought to be seen, but as you are.

October 20th, Palermo

Yesterday I arrived in Palermo slack of face, filthy of garb, and reached immediately for a telephone to call the friend of a friend. Then sat in a bar and waited. Why did the large, fat man sitting outside playing cards warn me to keep my eye constantly on the bike? Why did he want to help me find my friend? What about the Israeli who came up and said he was trying to find out whether he would be jailed if he went back to Israel now? What about the German-speaking waiter? Wouldn’t any of them have helped me towards food, bed and stable? I was glad to have my friends, to be taken to a grand restaurant, fine pasta and grilled fish. What did I miss?

Today I can view Palermo as a tourist – but last night, on the via Torremuzzo, I saw it as a film by Visconti or Fellini – a set piece of villains, freaks, saints and brawlers in the night.

Priorities

1. Ferry booking, Peter Harland, LBC, ST Notes and film, Triumph diagnosis.

This is a coded inventory of anxieties. I am obviously destined to live with them for a long time, but it contradicts the habit of a lifetime. Somehow I will have to learn to enjoy what my senses can grasp and not draw them in like a frightened snail until I’m sure it’s safe outside. Is this possible at the age of 42? I’m definitely up against time now – time spent and time to come.

2. Will the Tunisians let me in?

How will I recover my deposit from the piratical Tirrenhia [The shipping company] if they don’t? What on earth will I do if they don’t?

3. Why is the Sunday Times telex number wrong? UK MOTNE LONDON indeed!!! Cost me 500 lire for a nonsensical waste of time.

4. Will I ever get through to Harland?

5. Is there something very wrong with the bike if it does three pints in a thousand miles? Obviously.

6. Can I cure it alone? So on and on.

Each problem solved opens doors to new ones. I must find it in me to go on solving them and still say – To hell with them! Obviously though if I’m to keep going on the money I have, I must keep out of big cities most of the time.

[A week or so before leaving England, Harry Evans, the Editor of the Sunday Times who also rode a bike, arranged for us both to get schooled by the motorcycle police. In those days it was still a rule to give hand signals.]

Sergeants Farmer, Fittal, and Easthaugh, I’ve been thinking of you. Every time I take the wrong line on a bend or find myself hopelessly confused between wanting to twist the throttle and signal with my right hand; I feel your eyes heavy but benign on my neck.

“He’s a good lad,” they say. “He’s trying, but he’ll never be one of us.”

Who are those three dashing sergeants? They are all at the police driving school at Hendon, and I was privileged to spend two days with them before leaving England, to see what motorcycle policemen are made of. The experience had a profound effect on me, which extended far beyond mere motorcycle matters. I learned for the first time in fifteen years of miscellaneous driving what that boring old highway code was really about; what it feels like to be safe on the road. As a motorcyclist I feel much more competent to stay out of trouble, but if only car drivers could get just a glimpse of the dangers of the road as a motorcyclist sees them, I would be elated. I include myself. Three months before leaving on this marathon I was an ordinary driver on four wheels. What I did then makes me shudder.

For one thing, car drivers fondly imagine that a motorcyclist can always squeeze by somehow. In fact, on two wheels you take your life in your hands on many roads going to the edge to avoid a road hog. On country roads particularly where there is often loose grit or gravel at the edge. I’ve fallen twice in this way, fortunately at slow speeds. Once at high speed and face-to-face with a four-wheeled assassin filling my side of the road I was just lucky.

Then car drivers suppose that other drivers trust them to do the right thing. On a motorcycle you dare not trust anyone. If you see a car rushing up towards you on a side road, you can’t afford to assume he’s going to brake at the last moment. And the avoiding action you take, whether you brake, swerve, or accelerate, is likely to carry its own risks. Car drivers who signal badly, or not at all are a hazard to all traffic, but to motorcyclists they are positively lethal. And so on and on. . . . . .

[Well, here endeth the lesson. I don’t think even police riders do hand signals anymore, and my feeling is that car drivers are generally more controlled today than they were then, more by regulation than by themselves. But you still dare not take your eyes off them.]

I wanted to reproduce here what I discovered in Roggiano in 2001, but to my surprise and disgust Adobe has locked me out of the pdf files of my own book, and I have no time now to sort this out. Suffice to say, when I arrived Zanfini had been dead just a few years. A school in Roggiano had been named after him. His widow was curiously reticent to talk about their history. I formed an opinion, quite unfounded, that there had been some strain on their relationship, and that it might have had to do with the young woman dressed in black, who had so impressed me when I first arrived. At any rate, Zanfini appears to have succeeded with his program, and was well remembered, but the buildings so ardently created, were now obsolete and derelict.

Cheers, everyone, until we meet again.

Ted

On October 18th I was still making my way down Italy to Sicily, and the ferry that would take me to North Africa. With my eyes firmly fixed on the unknown world ahead of me I wasn’t expecting to experience anything much worth recording, but in Roggiano, Calabria, I was reminded that the adventure can begin anywhere, when Giuseppe Zanfini made his operatic appearance in my life.

Please read last week’s notes first if you haven’t already.

Here’s what I wrote in my notebook:

“When I was eighteen, I was a fascist from my eyes to my boots.” His hands described the very ample parts of himself that included, but his plumply energetic features indicated that he was far beyond making excuses.

“I volunteered for the army to go to war. I was in officer school. Then in Sicily, four years after, came my first real battle. I heard the toot toot of the bugle “ – he went toot toot – “that meant go to prepare arms. I was in the tent to pick up my gun and clean it and I thought, this time it is not for a paper cut-out figure. This time you will have to kill real men, and I knew then that I couldn’t. Not to kill men with mothers like mine, with children – men who come from homes like mine which will be in misery.”

Short of wringing tears from his eyes Signor Zanfini relived his moment of conversion in front of me, behind his office desk. In a measured hush he spoke of love and brotherhood, his face flitting between solemnity and ecstasy. As the battle progressed he wiped blood – the blood of other men – from his face. He represented graphically how other men had lost a hand, an eye, a leg.

“After the battle the Colonel wanted to give me a decoration because I had stayed on my feet through the battle, but I refused. I told him I would never bring myself to kill another man. He said he understood but asked me only to keep my sentiments to myself. Three months later was armistice and the colonel was able to sign my permission to go to university. There in the new democratic Italy I studied to become a teacher and came home to Roggiano to teach others that we must have peace not war.”

“Then I saw that our men were returning from the prison camps and talking to their families at the fireside about the war. And then soon the children in the square were rushing around saying ‘Bang, bang’ and ‘Boom, boom’ playing at war. And I saw that although we had already lost one war, we were in danger of losing an even bigger one around the hearth.”

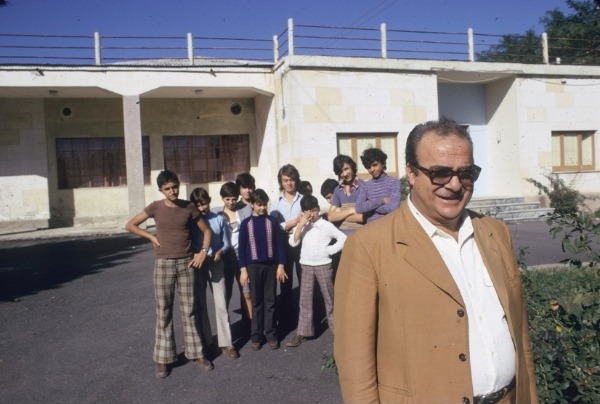

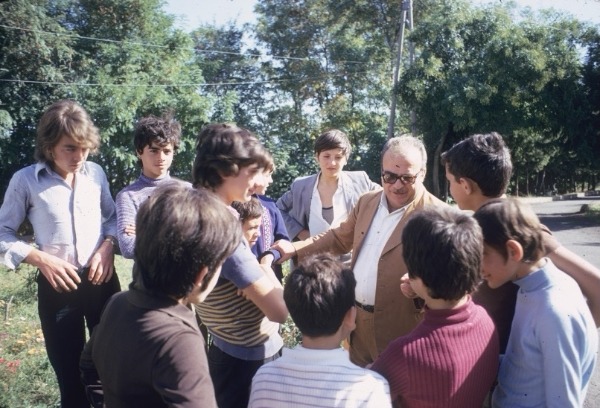

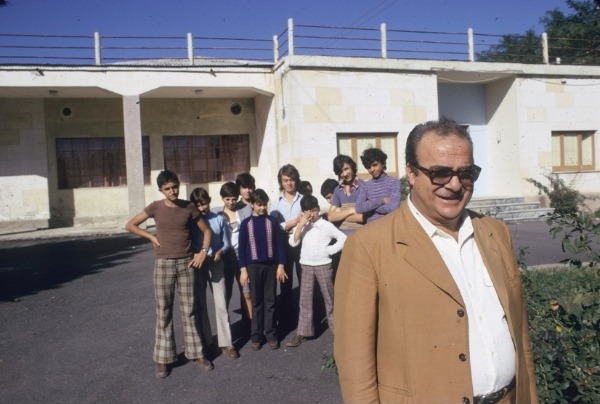

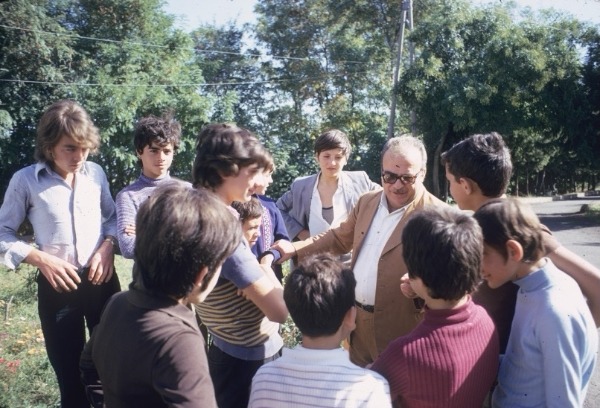

Zanfini was determined that children should not grow up to worship war. He propagandised ceaselessly, in school and out. In 1949 he joined in with the illiteracy campaign to open a small cultural centre in Roggiano. Nearly fifteen years later his energy and imagination (supported by his undoubted dramatic ability) has had great influence. It has drawn visitors, expert and student alike, from 84 centres to watch signor Zanfini’s cultural program at work in a peasant community. Both Swansea University and Manchester (through Prof. Ross Waller) have a permanent connection with Roggiano and send many students from undeveloped countries who may see how to tackle similar problems in Asia and Africa.

Because Roggiano is in Calabria, the heart of the Mezzogiorno and, at the end of the war, still largely cut off from the mainstream of European thought and progress. Now Zanfini is at the point of seeing his last and most extensive project realised. After seven years of bargaining and persuasion he has brought the mayors of the fourteen communes of Esore – seven Christian Democrats, four Communists, three Socialists – together to agree on one school for the whole region. A school not just for children, but for adults too. A centre where the skills learned by the children can be put to use by the community, where chemistry students can tell the peasants what their soil needs, etc.

He unfolded his plan and pinned it to the wall.

“All this,” he said – and there was a lot of it; some thirty buildings or more, with sports stadium, pavilion, theatre, and so on – “all this will cost only an eighth of what must be spent if each of the communes were to build their own necessary schools.

“Yesterday I had the councilors of the Regional Government of Calabria here to make their own final decision. They have agreed that it must go ahead. Now all we are waiting for is Rome and the law. The principle of comprehensive education was already accepted by the previous minister of education. But even if the Government said no, the people of Calabria would be determined to go through with it somehow.”

“Another march on Rome?” I suggested jokingly.

“No,” he said. “Never. There must never be another march anywhere.” And that same ineffable sweetness flooded his face, which only in Italy could carry conviction. “Peace and love. Love and peace.”

Now that he’s fifty he’s ready to retire. Area involved about 60 Km X 35

All decisions on community centre are unanimous.

Friday October 19th

Took pictures of Zanfini on 28mm lens. Then usual hour to pack everything. Got away about 10.30. Changed money in Roggiano. Every time the rate gets worse. In Rapallo 600 lire per $, in Rome between 583 and 575, in Roggiano 565, a 6% drop in value. What will it be in Palermo?

The last ten days have been a fairly comfortable prelude to the adventure, through familiar country, although I oddly failed to note the night outside Florence where, refusing to go to a hotel and finding all the camp sites locked I spent the night sleeping triumphantly on the bike under my umbrella.

An audience in Florence, the night I slept on the bike under my umbrella

Tuesday November 16th

Left Rome. Stopped in Latina for coffee.

Too hot. Tied chaps round luggage and lost them.

Spent the most miserable afternoon I can remember looking in vain over 25 km of road and then cursing, whining, wishing and regretting everything I had ever done. Not helped by impossibility of finding anywhere to put tent.

At last, at Larga Patrici, just before Naples, a beachy site. Felt better in tent. Terrible condensation in morning. Stopped to dry out tent on autostrada to Regio just after Pollo. Tent filled like a sail. Took 200mm pix of caterpillar and mountains. Also frames, 28mm, 3,4,5,6,7 of bike against mountain and villages. A little further on, a town against a mountain.

Then came off A3 at 1.15 to find some hot food. Buonapiticola provided a ‘Pizzeria’ where I asked for spaghetti. Passed old lady, just like Lucy, gathering vegetables in garden. Spaghetti at 300 lira was too expensive, but I regret the noise I made. Northern male strikes again.

From the autostrada

This business of the chaps has provoked a great many notions. I suppose a journey of this sort is bound to search out one’s weaknesses as well as expose other underlying traits. While the solitude is not so apparent nor the strain so monotonous as in a wilderness or on the high seas, it may in in its own way be as telling.

Alone in a yacht or on polar expeditions I’ve heard it said that men are inclined to swing between much greater extremes of misery and ecstasy. My own reaction to the loss of the chaps was naturally profound, but it seemed to eat deeper into me in a bitter fashion as I rode along in the night, going nowhere, looking for somewhere, almost crying with vexation, longing, self-pity and love for Jo, whom I seemed to have abandoned just as stupidly as I did the garment her loving hands had made to protect me.

As I rode through the night, from one locked campsite to another, I composed endless letters to her expressing my feelings and simply couldn’t wait to find somewhere to get my pen to paper. Yet as soon as I got somewhere and was settled into the tent, my anguish seemed to entirely evaporate, and I was forced to observe my own apparent fickleness with some disgust while feeling far too relieved to be really unhappy even about that.

This was written while waiting for the spaghetti to cook.

Back on A3. Viaducts between mountains become ever more spectacular. Took 28mm pic of one being built. At 4pm decided to leave A3 in search of a place to pitch my tent. Night falls here at about 5pm. Came to town called Roggiano. Lads shouted, children rushed up. Found a group of men in the square, in carefully pressed suits. One spoke English. They were curious and he spoke to me. I wanted to buy coffee. He indicated the alimentari shop which opened at 4.30. Bought an orange soda then went back to talk to them. Point is, I had time on my hands. Result was that eventually he said there’s an international centre up the hill. UNESCO he said. They would give me a bed if I said I was a journalist.

A cavalcade of young boys (where do the young girls go?) escorted me for 500 metres whooping and shouting as I maneouvered the Triumph among them. A young man with renaissance features and facial hair to match received me kindly in halting French (I spoke no Italian worth speaking with). He described the basic idea of the centre , which consisted of a number of low, flat buildings, pastel pebble-dash, steel-frame windows, in gravel paths and thin grass. It started as a centre for UNLA – the national campaign against illiteracy in 1949. It has become a cultural centre for the region. It has a staff of four full-time, himself, his father, another teacher and a secretary.

All the buildings were erected by the people of the region in their spare time, including bedrooms for those who have to come a long way to Roggiano from one of the other 14 villages scattered around the river Esaro. In a great communal hall a grave young woman in black brought a tray of coffee and cups and stood by us patiently while we drank. Earlier I had watched her with a vast bundle of laundry at least as tall as herself balanced on her head, walking easily through a doorway without an inch to spare on either side.

I was received by the father, Guiseppe Zanfini, in his office. When he had finished his telephone call he beamed across at me with such concentrated benevolence and hospitality that I wanted immediately to vote him into office, any office. Then without preamble and scarcely a pleasantry he launched directly and astonishingly into his story.

Next week: Zanfini’s story.

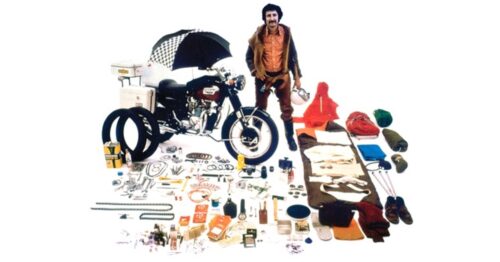

The journey began in confusion.

At the time I had no place of my own in London and was staying in Putney with friends, John, Graham and Diane, who had to put up with my chaotic preparations. In my room I had the three fibre-glass boxes that were attached to the bike and spent endless hours assembling, and sorting and often discarding the eclectic assortment of things I thought I might need in remote parts of the world of which I knew nothing. Everything was last minute. Even the north-African visas came with only days to spare.

I was due to leave on Saturday, October 6th. My first notes, made on Friday, began with a list of numbers:

American Express Card No: 421 109 604 7 800AX

Midland A/c No: 90739812

Traveller cheque serial Nos. RA72 443 021/5 ($100)

Passport number 535439A Issued 10 Sep 1973

Previous passport number 575911 issued 14 June 1968

Domestic driving licence No 3A/1024534 Exp 3rd April 1976

Triumph registration number XRW964M

Naturalisation Cert. No. BZ233

Engine & Chassis Serial No. DH 31414

Insurance policy no. GB/105/L82d9857 (83) London & Lancashire

Sudan Air Ticket: (British Midland Airways) serial number 001580 5

Even though I was on a bike, Sudan required a return ticket by air for a visa.

Cable Credit Card No CW14602CW

Camera serial numbers: BODY 1 5386100/BODY 2 5413027/28mm 5838503/200mm5852279/55mm 6290789

Tony Morgan Telex No. 99291. Ask for Vera Dormer Tel 037576519

Triumph key nos. Ignition FS 913, Lock EJR 5 Both Union.

You will note the absence of mobile phone numbers and email addresses. Then followed an inventory of my wealth:

Cash. $600 US, Libya 5 Dinars, $Aus 10, Ethiopia 28 dollars, Zambia 10 kwatcha Brazil 38.5 cruzeiros, Francs 50, Balance at bank (all cheques cleared) £1000

I was supposed to start the journey from the Sunday Times office building in Grays Inn road on Saturday so that the paper could print the news of my departure on Sunday.

Saturday 6th October

[Still in Putney]

I started packing, writing letters for Peter Harland to send to Sudan, trying to sort out rubbish, hours sped by, 4pm still not finished.

John enters to say Egypt and Israel are at war. Outside it’s raining heavily, with thunder. Graham and Cheryl [an Australian couple also staying there] are in a terrible state about their air ticket. A strange mood. Everything feels wrong. Jo [my girlfriend in France] is to ring me at Orsett at 7.

At 6pm I am at the ST. The war progresses and must be taken seriously. Thus, on the very day I leave, after six months of preparation, all my arrangements are thrown into confusion. It may even mean going round the world in the opposite direction. A card has arrived at the ST wishing me well, from Mary & David Abercrombie. I pick up TriX film and ST cuttings, and leave. Outside in the rain I drop Mary’s card in the gutter where it quickly becomes muddy litter. Bike won’t start. And I have left my leathers at Putney, where I have already been bid a hero’s farewell.

[Well, the bike did start after all. I rode back to Putney for the “leathers” – some beautiful chaps that Jo had made for me – and then rode on to Essex. Although the paper said I was riding to Folkestone that night I had always planned to spend two more days before leaving England. Tony Morgan, another friend, had invited me to spend the night at his palatial home at Orsett, and the following day I said goodbye to my mother, at Wickford.]

Drive through rain to Orsett. Musto trousers are not waterproof, but next best thing.

[There was no waterproof clothing for bikers that I could find. Tony had suggested tunic and trousers made for yachtsmen made by his friend Musto.]

At Orsett all turns much better. Champagne. Happy times. Jo has called. I’ll ring her on Sunday morning.

Sunday 7th

Mostly at Orsett, reading in ST about my departure from Folkestone the night before. Repacking, timing engine, etc. Then at 5pm to Wickford.

Monday 8th

Leave at 7.15. Arrive Dover 9.30. Buy umbrella. Take 10.30 hovercraft at 11.30. “Electrical faults.” Don’t believe it. Probably just saving money if they can get two loads into the 11.30 trip. Drive as far as Orleans.

Canterbury lamb. Oast houses. Orchards. Sugar beet in France. Huge area devoted to it. Grandvilliers, north of Paris. “Son Parking.” “Sa Zone Industrielle.” Uneventful drive to Orleans. Hotel du Martron. Garage. Bushy gray-haired proprietor. Happy. Had a Matchless and an AJS. Thinks they were much better.

“La Baraque.” “La Baraque Brulée.”

[Two villages]

Tuesday 9th

Fog out of Orleans. 100 miles. Nearly killed on road into Millau. How to allow for suicidal over takers? Remember other roads, fast narrow roads in and out of provincial towns and dangerous home-bound traffic at dusk. I shall have to remember. Slow start. Slow finish. It takes an effort of will to get the speed down. The will to survive.

Wednesday 10th

Millau. The International Hotel. Memories of steam engines wafting in the smoky air. Jo on the plateau. Repacking. Tomatoes and green peppers. Home. The barn so neat, so complete looking. Love. Tiredness. Calm.

Thursday 11th

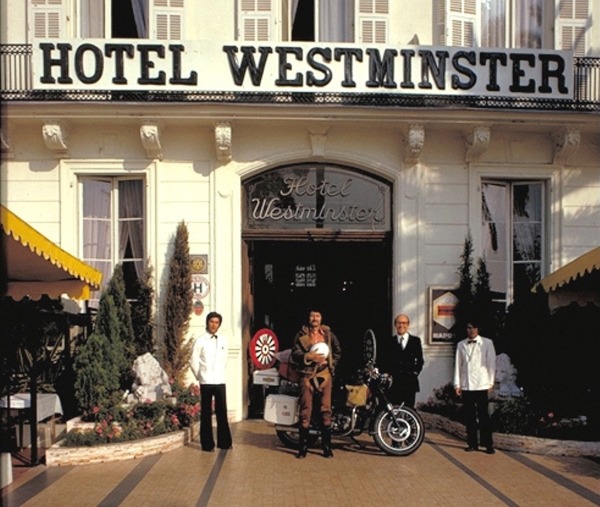

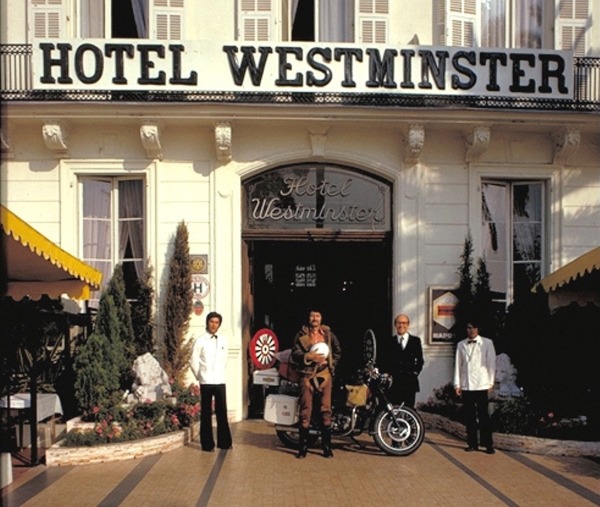

To Nice. Easy ride. Autoroute (9 NF). Pierre welcoming. [Pierre Guirand was the director of the Westminster Hotel on the Promenade des Anglais. I knew him from my newspaper days.] Meet two American actors and a girlfriend, Ruth. They are Tom Skerrit (c/o William Morris) and Keith Carradine (c/o I.F.A ) in LA.

Did push the bike over outside Gignac, fiddling with the horn. Got a rough taste of what it will be like having to pick it up. In Nice repacked once more. Now have the sleeping bag outside the sack on top with the waterproofs in plastic. Washing bag on top box, with knife and sausage. Also tightened up rear suspension to maximum.

Friday 12th

Felt sleazy. Did some exercise. 7 pushups maximum. Thought again about picking up bike, regret weak arms. Down for coffee, croissant on terrace, having fetched bike from garage. The picture with Pierre. Can’t get the measure of him.

[A woman insists I must be going to Sierra Leone.]

“When in Sierra Leone. Robert Snowden (World Bank). Diana Pitt (his wife is her first cousin.) Aziz 6791108 / Ferahi 4249967.”

Sat/Sunday/Monday

In Rome. First day exclusively on cleaning and looking at the bike. Reset tappet clearances. Rt hand inlet had little, if any. Machine is now quieter, but also vibration just as pronounced. Primary chain seems a trifle loose, but every time I adjust it, it seems to find this same tension. So I’ll see if it stays or gets slacker. Cleaned it. Tightened front crankcase bolt (LH).

Andrew and Gabrielle Hale [newspaper contacts] very hospitable, though he gets up tight often and shows a waspish front to deter invasions of privacy. A pained look that must have developed over years of coping with Italian gusto.

Pensione “Kent House” on via delle Crocce. 3,500 lire a night for three bed room. Family restaurant next door (on the right, facing houses). 2000 lire a meal. (Etrusca in Vittoria is cheaper).

Monday recorded for LBC and felt unhappy about it.

[A new radio station had opened in London and I had an arrangement to record stuff and send them tapes.]

Faced first problems of postage. Wrote out notes for ST. Seemed to spend ages packing again, as always. Tried to buy a few simple things and found them appallingly expensive or unobtainable. (ie. Roll of tape for 500 lire). Must be like an Italian trying to buy ironmongery in Mayfair. Met Oswaldo Marino and learned a few things.

Next week: To Roggiano

This has been an unusual week. In France there has been a day of nationwide strikes because people think the government isn’t giving them what they want, but they can’t seem to elect a government that will, probably because no such government could exist.

In England I witnessed, on TV of course, the most elaborate and expensive act of sycophancy ever devised by any government in the history of the world to flatter one person, Donald Trump, in the desperate hope that he will really think he deserves it. They seem to have succeeded.

Next week, back to reality.

With this excerpt I’m only days away from the end of a four-year journey, approaching the Mediterranean coast of Turkey, still in the company of Ted Holst and Mina on their BMW.

Still Monday June 6th

At Mersin a fertiliser factory is producing the worst smoke pollution I’ve ever seen. A pall of salmon smoke completely obscures the road and the country around.

Trying to get to Silifke before dark. Tried at a MoCamp (BP). Prices were too high, and I thought it was all too lavish. We went on and spotted the “Yilmaz” restaurant overlooking bay. They let us camp on a terrace, and we ate and drank – fish, salad and wine – for 48 Lira each.

Tuesday June 7th

Stayed at restaurant. Met two burly bulldozer mechanics who were liberal with fish and raki. Peter had difficulty accepting it. (He turned up just before lunch.) In afternoon another family came and dished out fruit and yoghurt. A lazy day.

[The question of which offers to accept and which to refuse can be tricky. I took the rather grandiose and self-serving view that since I was intending to give all my thoughts and experiences back to the world as a book, I was entitled to take from it whatever it offered. I was on a mission. Peter was not.]

Wednesday 8th

Left, and forgot to pack the fishing rod. Slept in woods before Alanya, with fire. Nice coast.

View from the road

Thursday 9th

To Antalya. Public campground on road to Kemer, on beach. Grilled kebab meat. Nice port. High stone walls. Fish restaurants. Cheap apricots. Dropped gloves twice in street.

Friday 10th

Next day left Pete and rode north. Then vibration started. We fiddled with timing and stuff.

[I guess Pete must have caught up with me.]

Lost lots of time, and stopped long way short of Afyon, the target. In small hotel, where French couple, coming the other way, joined us in trip to the Hamam, escorted by hotel owner and Turkish friend. All together in bath, while Turks waited outside. Afterwards lots of lewd remarks about “spielen” – and next morning the foolish scene in bedroom between Hennie [the French girl] and hotel keeper while Mark slept. So a good impression spoiled, but not too badly for us men. We are not Muslims.

Next day, Saturday, stopped again to camp behind BP station eating bread and sausage and cheese. So, Sunday into Istanbul.

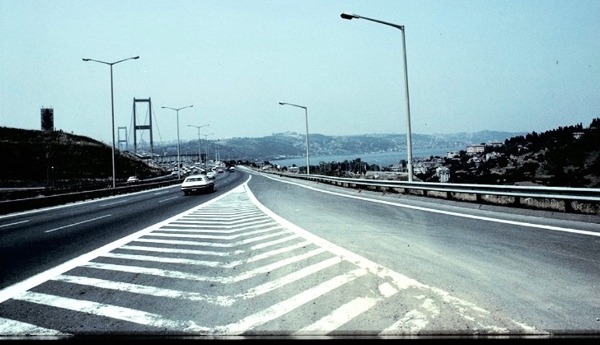

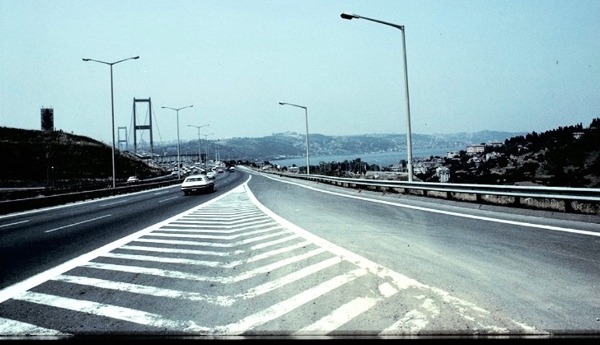

The bridge out of Asia – across the Bosphorus to Istanbul

[I spent three days in Istanbul and saw plenty but wrote nothing about it. I only have one very clear recollection. In a residential neighbourhood the three or four storey houses, built as a U, enclosed an open space where a long table was set up and people all ate and drank there together. I, a total stranger, was invited. I found it extraordinarily civilised.]

Thursday 16th

Left Istanbul at 12.00. Milometer reads 31310. Fresh oil to full mark. Fresh engine oil. Tank full of petrol and five lira in pocket.

Difficulty to find way out of Sultanahmet. Once on road vibration was as bad as after Antalya. Hot day. Met idiot driver who nearly pushed me off the road.

Retarded timing. No effect. Plugs white. Put on choke. No apparent change. Spent much time contemplating engine failure. Had to change another £10 [traveller’s cheque] in Tekirdag. Lunch of Köfte, rice etc, 23 Lira. Changed 235 Lira at border into 510 Drachma. Border is 150 miles from Istanbul. Called Hudut. Got to Kavela, slept under concrete skeleton in lovely bay. Good fish, chips, salad and retsina for 49 drachmae.

Next day Thessaloniki. Rained. Prisunic [supermarket]. Spent about 54. Got litre of oil. Balance in Petrol. Thought I was diddled by 6 Drachmae. Ran out of petrol 100 m from border. Had 10 Dinar given by mistake. Worth a litre. Got one and a half litres by mistake. Absurdity on Yugoslav side with money and coupons. Changed £10. Rode on through rain. Stopped for tea. Met Dieter’s bro-in-law. Hash story. We went on together, but he lost me just before Skopje. Thought I saw him pounding back on the other side of dual carriageway.

Tried motel. Awful little box for 114 Dinar (£4) Went out of town. Slept in field with tent. Did well. Next day changed £10 in Nisi and had scratch breakfast. On to Belgrade by 1.15. (Yugoslavs always sitting at empty tables).

From West Turkey the New German Empire. Every other car in Yugoslavia is Deutsch. Belgrade surprised me. So many tall blocks. They do well at apartment buildings it seems. Hwy runs in and out. Stopped for a moment on a grassy side turning. Already 225 miles today. Vibration varies. Loosening primary chain seemed to help. Alignment also better (next day). But still lot of ache in limbs. Now countryside changes. Lower lying. More prosperous. Tidy towns with churches. Stopped somewhere near Sisak. Altogether about 425 miles.

Friendly waiter in restaurant gives short measures in beer but good goulash. Camp at end of field. Again OK, but ground very bumpy. In morning first sign of backache, but not serious. Bread, chocolate and tea. Put in litre of oil. Began to think of reaching München today. Past Zagreb and Ljubljana.

On way, nastiest accident scene. Little car torn apart and two TIR trucks askew on road. Mother and 5-month baby dead. Great queues of traffic form in no time.

I skip past, exchange a word with TIR drivers, all standing around in singlets. Then on with no traffic ahead or behind. Made my journey easier. They didn’t give their lives for nothing. Very little though. Don’t know who was driving the car. The baby maybe would have had better instinct for survival. Strange how we lose the instinct in a car.

After Ljubljana spend my last Dinar on petrol. So £20 gone in Yugoslavia and almost all of it on petrol. New frontier roads, through broad mountain pass, to Villach where I was waved into Austria and met Gaby of Neckerman Reise. Also, the Grüss Gott witch with the goulash supper. But very gentle man in bank. There’s a jazz festival in Ljubljana. Oh God, No way.

Sunday 19th

To Spittal and then the amazing toll road under the mountains, Katschberg, etc. 4 endless tunnels. 50 schilling toll (£2). I burst out laughing. It seemed preposterous, but of course it’s in line with everything else. [What was I thinking? For once I simply can’t put my head back into that place. I may have been slightly nuts.]

Now lots of rain, and hail. But dry patches afterwards. Tank up once near Werfen. Petrol still over a £1 a gallon. To border. No formalities at all. Could have brought anything at all into Europe. Then the long, fast motorway to Munich, but I’m the slowest thing on it. And just at nightfall, in rain or drizzle, I pull up in the Rosenheimer Strasse and call Octavia [one of the German sisters I met in Ceylon] from a Gaststätte.

Wonderful. Home and dry after a lot of searching for house. Pleasant looking girl in VW which seems to be full of mongoloid idiots with faces pressed against windows.

Miles 32750. So, 1400 from Istanbul. Average 400 a day. 2 litres of oil – not quite. Bike fell over in Austria in rain. Had to lift it, but with back already bad put my body to severest strain. Felt it and laughed about it with Octavia.

2 days in München with O and one more alone. Meanwhile contact with Jackie Stewart and Mme Albaret in Paris about my things.

So I’m in Munich, and almost home, though where home is remains to be seen.

I began publishing these notes two and a half years ago – as single excerpts at first, from Cairo and Aswan, Chile and Ceylon and then, as I got into the fun of it, in sequence. But the sequence began halfway up South America, so most of my notes from the beginning of the journey have not yet graced your Sunday breakfast table (or wherever it is you read them).

Starting next week I’ll go back to the beginning of the story.

I am still thinking about how this might be made into a book. It presents some peculiar problems, but it could be beautiful. More words of encouragement from you would be welcome.

Leaving Iran.

Wednesday, June 1st

To border, meeting Ted and Mina by roadside. Then the endless snake of lorries lined on road – maybe a kilometre – waiting to be processed at border. They watched with non-committal eyes. Balkan drivers in shorts and short-sleeved shirts and sandals. Mostly Bulgarians. They pioneered the route – according to Ted. But what do they carry?

The Iran border was quick and easy. Though the police, again, seemed to be competing for the “Most Hostile Expression” award. Then from Iran through an archway into a muddy courtyard that was Turkey, where a mustachioed man in uniform waved me round like a maitre d’hotel from the Habsburg Empire.

We queued in customs before a man who was nervously new to the job and kept stopping to stare at papers and passports with a thoughtful faraway look.

From the border to Dogubayazit, and not a 100 yards down the road two small boys threw a stone and crawled off up a hillside. It was so prompt a fulfillment of the Turkish reputation, it was hilarious. They should be paid by the tourist office, who could supply them with polystyrene rocks.

At Igdir, at the Park restaurant, I stopped to wait for T&M and drank tea with two young Turks. One said he was a Marxist. I said I was police. Then brandished my CPF lighter. [What was that? I have no idea.] We had kebab, salad and bread. Immediately noticed that the food was far better flavoured. T says Greek food originated from Turkey and was better there. It was warm and pleasant in the garden. A few clouds in a blue summer sky. I set off contentedly, quite unprepared for what was to come. Winding off among a maze of peaks and valleys, ever higher, distant snowcap advancing, clouds growing fat and dark and sagging heavily, then drizzle into rain, tarmac into dirt, rock slides and mud, and cold until it began to penetrate that this was becoming an ordeal.

When I stopped once to smoke a cigarette under my umbrella, I found my fingers couldn’t handle the top stud of my jacket [Actually it was getting quite serious. I want to put more clothing under my jacket, but couldn’t take it off.] while a friendly shepherd watched with amused sympathy.

(Turks all remind me of unemployed workers in the Depression years – flat hats, old-style shirts, waistcoats and suits. The women wear shorter versions of the Afghan/Iran skirts and shawls, but later this changes dramatically and in the centre, after Kayseri , they wear those big bags with holes at the corner. Were they invented for warmth or as prevention against sudden rape. Back on the bike, wondering whether I would ever see the welcoming warmth of a tea cup again. Singing, flexing my muscles, trying to imagine the countryside on a fine day, trying to relax my neck muscles, so stiff I can’t turn my head, amazed that when I’m so close to home I should run into such extreme conditions, wondering how I had imagined that it was simply a matter of going up over a few passes and then down again, trying to visualise this crumpled landscape of rocks extending back to the Himalayas and North to the Caucasus and realising all the time that the cold was getting into me without quite knowing why. When I did get to the village before Horasen, and got off, I sat among the men in the tea shop laughing and shaking – couldn’t stop shaking – like a puppet with somebody jerking the strings. After half an hour, and several teas, I put on leather trousers – would have used “long johns” if I hadn’t sent them back from Delhi, ski socks, jumper and scarf. People were nice – though one man was desperate to swap cigarettes.

All the way little boys who weren’t throwing stones held two fingers in a wide V over their lips to ask for cigarettes. From Horasen to Erzerum was much easier, though higher still and above snow. Erzerum also a surprise. Mountain town, cobbled streets weaving. Hotels full. Took room at new hotel, Bohara, run by young men, embarrassed amateurs. Room cost 72 ($4) but plumbing was incomplete and no water. T &M caught me at road into Erzerum. We ate together (good food) and went to a Furini where a relaxed baker with fine features wielded his huge baker’s paddle and tossed dough from his little mezzanine dough house above the oven onto the wooden platform below.

Thursday, 2nd

Left T&M in their hotel and set off for Sivas. No rain, lovely ride in mountains. Two high passes. Over the second, guard humour, then comic disaster as I slid into clay gulley by roadside. Rode bike out with much effort then dropped it back down . . . .in ditch. Fought to get everything off and bike upright before petrol all ran out. Much cursing and swearing. At last set off, but visor dirty. Parked again on camber to clean up and passing bus blew bike over in same humiliating position. My laughter was hysterical. Bus driver passed grinning. Then while I was fighting to get bike upright a Hungaro-camion driver stopped his giant truck (and his partner’s) and leapt out to help me. Very surprised and grateful.

Down to Erzincan to eat kebab (off big spit: where did I see that before?) and wander along shops. Copper jug $8. Too much. Petrol in Turkey 2.80 a litre – 75 cents a gallon (Iran 50 cents – 8 Rials litre)

Sivas at 4pm. Huge excavation in main street. With concrete channels being set in under road. Shared bedroom for 25 lira. Met Mark, Hennie and Peter in restaurant.

Friday, 3rd

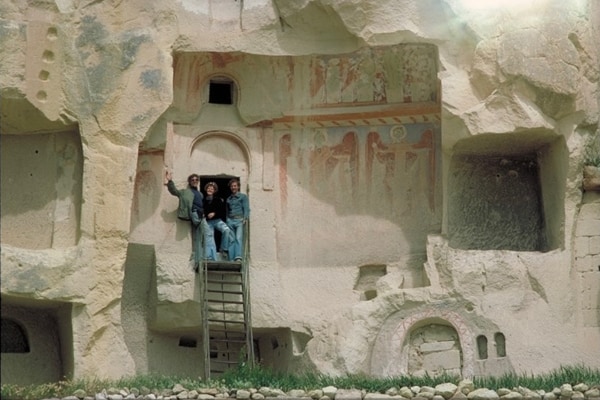

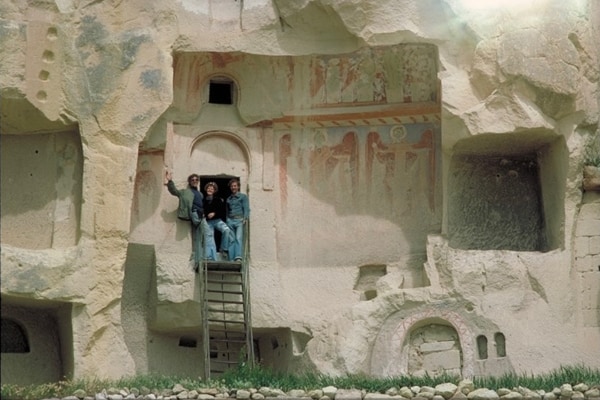

In convoy to Urgüp. Cimenli camping. Bargained for 15 lira each. Two good days – one just hanging about, one to see the troglodyte churches at Göreme and the fantastic eroded landscape of cones around there.

Overcast sky turns to gale and hail at night. Morning turns to drenching rain. Peter turns out to have no raingear, not even gloves. We have to leave him and make the soaking ride down to the main road to Adana. First half hour was worst. Then a dry spell. Then more rain on a broad table-land of wheat, etc. Then a tea stop while the sun came out. On to big jetu on Antara-Adana road just as we seem to be heading over a great range of snowy mountains – Taurus range. Road sweeps sharp left, along river, downhill. Then up to last pass and among endless stream of petrol tankers down to the coast.

Mercedes driver rushing in front of me at impossible speed seen seconds later after a head-on collision with another Merc. His face, as he gets out, a picture of utter defeat and resignation. Probably he had nothing to hurry for, but imagine what it might have meant. A last glimpse of someone he loved? A million dollar deal? A last chance to escape jail?

On the way we talked about Das Rollende Hotel [the bus with its 39 bed slots in three layers.] The idea that each slot was actually a coffin. At the end, 39 jets of gas ignite and incinerate each compartment, and 39 urns pop out. “Holiday of a Lifetime.”

I’m off to my own holiday now. Find me here again in September. All the best.

It is noticeable that I was much more concerned with the condition of the bike, now, than by what was going on around me. A chronic problem with the Tiger 100 was the tendency of the rocker caps or pushrod covers– often called “hot cross buns” because of the grooves on top – to come unscrewed and loose oil. Loctite was supposed to be the solution, but since they had to be removed from time to time there could never be a permanent fix.

I’m now leaving Kandahar on my way to the frontier with Iran.

Thursday, May 19th

To Herat. Long ride. 130 miles (?) Oil is now pouring out. At Sangan Hotel with Holst again. Two days. 1st day try to cure leaks with silicone rubber donated by Mark Fry, US biker on BMW. Doesn’t work.

Second day, more thorough job on push rod covers. Seems to work. The pelicans. The Mosque. The fastest horse-drawn carts yet.

Sunday, 22nd

To Mashad. [Iran.] The frontier. Hell on both sides. To camp site. Lost the Holsts again.

[What I remember now of that frontier was tourist cars and trailers being almost dismantled by customs officials looking for drugs, with storms of paper products (toilet, tissue, towels) blowing across the landscape.]

Monday, 23rd

Stay in Mashad, tinkering and trying to finish letter to Carol. Holst arrives, having lost his gear lever before the frontier yesterday.

Tuesday, 24th

Breakfast meeting with so-called maths teacher who takes me to the Magic Carpet Shop. Then off. Cross desert and mountain pass to rain and Gorgan. Different world – really Slav. Night on cement balcony over bus depot. But OK finally.

Wednesday, 25th. To Gorgan

[Somewhere – I can’t remember how – I got an introduction to a family called Havranek, at Rasht on the Caspian coast and I headed that way rather than to Tehran.]

Beyond Gorgan weather starts breaking up. Towards mountains (Elburtz) some rain. Passes in cloud. On other side, first rich black soil in a long time. Rice fields. Towns have a more European look. Gorgan in rain. At 2nd hotel small man with bristled aging face insists I can have a room. How much can you pay, 200?, 300? Hopeless of getting anything cheaper I agree. But he is not to do with hotel. A truck driver who worked as a young man on BP rigs nr Aberdeen. Eat a chalo Kabab Morg (chicken) and he buys me a tumblerful of vodka, to be taken with pickled garlic. And there is not a bed except for 400 rials. But he rings the Tourist Home. Eventually go back there. And after showing me rooms at 200 or more, shows me bed outside on terrace above bus station, for 70, paid in advance. But bed is comfortable. Next day I drive out through the baksheesh barrier. Old gent in brown hunting clothes with stick is chanting a haunting song, and begging. In restaurant men eat like king-pigs while women huddle abjectly outside in drizzle.

Thursday, 26th. To Rasht

From Gorgan to Rasht along coast. Holiday villas all the way – in all styles. Much unfinished building, small resort towns, with railed-in parks, flower gardens. Coastline not very attractive. Much rain, which consolidates over Rasht. How will I find Havranek? Settle on going to biggest hotel I can find and trying for telephone number. But Iran Hotel receptionist knows him. Two Germans translate. All is well.

Mud on my boots, on my visor, in my eye. One well-directed spray from passing truck and I have to stop. A perfectly opaque screen forms instantly. I wondered why I had the Belstaff suit. Now I know. It’s disgusting on the outside but lovely to be inside. The bike is smothered. Not since the Altiplano like this. Geography is full of surprises – some nasty – never anticipated. Such filthy weather. Is it all the Caspian? And the mountains. My chin feels as though it’s been skinned by a thousand little knives. The huge TIR juggernauts roll on, pushing the air around. I look up into the cabs as I try to pass. It’s a different world in there. A young, blond man in shirt sleeves sits as tho’ at his office desk with blank eyes. Is there music and constant running coffee in there? They run in fleets. P.I.E. Hungarocamion – advertising offices in Budapest, London, Malmo, Zurich – with phone and telex numbers. Always at a steady pace 60 or 70 mph. Impeccable driving – signals. Paintwork and canvas. The rest of the traffic buzzes around them like bees around a beer.

Dino’s brother once abandoned a tour bus full of ladies at Qazvin (where they had no right to be) and ran off with the money. Hi family had to settle the scandal.

Melh Bank – big horseshoe shaped hall. But people here want to do business, It goes fast. Despite comments of Havranek family.

Conversations about We and They – always suspect. In Persian cafes the chairs are all set sideways at table with their backs to the wall.

4 nights, 3 days with the Havraneks. Lots of booze, wine, cigarettes.

[Surprisingly I don’t mention the caviar – of which there was plenty. A cherished memory.]

2 days of slight feverishness. Did I come off the malaria pill too soon? Third day OK. Dino & Maggie arrive on third day. Dino gets his Yamaha trials bike out. Very strange feeling. Light, high, very close ratios, hard to change, 450 cc single cylinder, no fly wheel.

Sunday, 29th

To Tehran. Easy run, but big climb among dusty green hills, and rivers, expecting to go over top and down again, but it’s a plateau. Very cold at first. Through Qazvin. Then the main artery, but its not so bad. Hop onto freeway but get kicked off by police after 20 miles. “Get”, he shouts, pointing. “Get. Get.”

British embassy in huge walled enclosure. Consulate like prison gate. Wait an hour for opening (Was lucky. Closes Friday and Saturday). At first they say No clearance. Then find telex message. 15 minutes and the renewal is done. And Amexco has the money from Tony, plus a letter. So to stay with Judy and Davoud Ismaeli and their daughters. Dino & Maggie are there too. We go to eat at Jap place (huki) and then to see Papillon. Sleep well on carpet. Breakfast with girls, then off to town. After bank.

Monday, 30th

To Zanjan, and once again rain and mud. Tea in small tea house full of avuncular Persians and song birds in cages. Share bedroom for three. 110 rials.

Tuesday, May 31st

On to Tabriz. Clear day. Roads are very good. Countryside is beautiful, pastoral, running between ranges. At Tabriz buy Turkish money, then on to escape huge raincloud. Stop 20kms on for lunch. Then to Marand. Remarkable town in great bowl of rock. Vertical faces all round with square building seemingly glued to rock.

Man in road said “Hello. Fuck off.” Got sucked into new hotel. Room for 200. Ill-favoured man kept on at me about shit. “Tourists like shit. I have shit. My brother is in police,” etc. I’ve come to hate that conspiratorial grin – the most potent of the various ways in which all the sharp youths all over the world try to establish instant intimacy.

Somewhere along the way – probably after Marand – I was invited into a family home for the night and enjoyed what I assume was a perfectly traditional Iranian evening and night, sleeping on rugs rolled out from cupboards in the wall. Wonderful hospitality.

Next week’s will be the last of this series of notes. After that I will be in the UK, visiting first Nick Sanders’ rally in Wales and later Paddy Tyson’s wonderful Overland Event near Oxford. So, until next week…

As seen from Europe, in those days (maybe still today) Afghanistan seemed a very distant country, but for me then in Kabul, France seemed just around the corner. Having to cross Iran and Turkey and the Balkans to get there seemed to offer no problem at all – how different my attitude from when I started in North Africa. The exigencies of travel didn’t bother me, but after three and a half years on the road I was tired, and glad of company to lift my spirits. Ted Holst and his oriental companion were also going my way and a loose relationship with them was comforting.

Scenes from Afghanistan

On the road to Kabul

My first poppy field

Tuesday, May 17th

Met Holst and Mina-san again in the Miami restaurant two nights ago. Yesterday we ate dinner at Sikris – getting a lift in a Mercedes from young man whose wealth had not saved him from the army. Meal was too rich. Ted was very sick. I was less so. From what? Mina later became sick, and hers lasted longer. Yesterday I called consulate. Afghan employee called Dona. No reply yet. Most of my week in Kabul has been spent recovering my centre of gravity. Had been unable to find myself.

[An anthropologist friend in London had recommended that I visit an American, Louis Dupree, in Kabul. Three years later he was still there – an established luminary, very much a Southern Gentleman – living in a house with Nancy Hatch. He was welcoming. Also at his house I met again Peter Wass whom I had met in Nairobi, when he gave me the elephant hair bracelets for his sister in Queensland.]

Particularly bad last Friday on my first visit to Dupree’s house. (Louis and Nancy Hatch). The five o’clock follies. Louis talks like a man who hopes his words will hold the sky up. – “hot as pussy on a Saturday night in a mining town,” his elaborate Southern metaphors are overdrawn. He specialises in iconoclasm but it’s not quite profound enough – not integrated. Second visit on Monday was much better for me. Extraordinary meeting with Peter Wass. He interrogates Dupree on Africa in general. What crops, etc, in particular. They are sparring. Both are basically contemptuous of each other but maintain a wary respect. Wass admits to trying to do good. Dupree claims to have given it up (when I labelled them as agents of progress.)

They discuss – we discuss – the effects of taking roads to the villages. Brings the city entrepreneurs direct to the peasants, who are no match. The despised middleman is cut out, but he was the buffer and has his uses.

Louis castigates the Helman dam and irrigation project. He says it is silting up – ‘not administered’ – i.e the Afghans now in charge don’t do it properly. (It’s a US project but they didn’t carry it right through.) He prefers many small catchments on a village scale. His slogan is “take the politics to the villages.”

Wass is part of a UK project to stabilise wheat prices in the general area. Once based in Beirut – now in Amman, where he and Diane live. “We fight furiously once a fortnight but thank God we have a normal marriage” – referring to his sister and Brian Adams.

Nancy does a guidebook.

At Embassy my first meeting is with Ian Hughes – Acting vice-consul, probably the Security/Intelligence man. Very bland, close and maladroit. “Funnily enough I read your piece about Australia in the magazine.” No comment. Are you busy? I ask. Rather, he says, with all the Hippies. After work? I prompt. Pretty tied up, he says. Are you staying a few days? Then I’ll probably see you around town, he says brightly. Wants nothing to do with me. I do see him around town once on Sunday morning in the impossible dark suit and high white collar, with the Embassy Land Rover, picking up smart tourists in Afghani coats – for the church service perhaps? Or to visit the jail? I am not psychologically fit to mix it with him and let it go by. They all behave as though an armed coup was imminent.

At the Green hotel heavily carpeted public rooms. English woman approaches me. Crisp upper-class style, but no courtesy. (“Show this man the bathroom”) She wants 30 Afs to [illegible]. I say I think 10 Afs is normal. “Good luck,” she says, and turns on her heel and strides off. Business is abrasive in Afghanistan.

[I had a fancy to buy a Russian samovar.]

The samovar hunt. In and out constantly. Once I’m offered one for $45. Next day it’s refused. Another time I’m offered another for the price. When I go back to get it the brother says, “No it’s not ours. I’m just repairing it for some Germans”. But the shops are loaded with goodies. Inlaid pistols, jugs, trays, mugs, knives, rugs, teapots, ‘lunch boxes’, etc. At the Kabul Hotel – a $10 bonus. Followed by rain and bedbugs. The Sikhs at the Khoresan constantly trying to diddle me out of a dollar and finally undercharging me. The Istanbul; 24hrs restaurant, and the splendid Abdul, whom I took for a Turk, perched cross-legged behind the counter with his high domed head and utterly cynical expression, though less cynical in fact than his young partner full of bonhomie and greed.

Today at consulate again., but no message. Dona says they’ll refer clearance to Teheran. So I set out for Ghazni [about 100 miles] to catch up with Holst.

The over-friendly man in the US car who leads us too fast into town.

“You want a ho-tel? Come on!” His room for 120 Afs. “Special student price.” Hah!

The robes worn by women – finely pleated. Underneath, often trousers and shoes by St. Laurent – quasi.

Russians walk leaning forward from the waist, shoulders back.

Traffic police dressed like Germans – in grey one-piece suits. With lots of straps and belts. Was it Calcutta where the police wear a harness to support an umbrella?

Ghazni:

Hotel with Persian name. Wide street of dirt. Horses and carts dashing past, full gallop. Later find Holst at campsite. Next to Col. Gregory’s broken down Comex bus (Commonwealth Expedition.) Fleet of seven buses named after Commonwealth places. Ie. Ontario. Old style enthusiasm. Finale at Wells Cathedral service.

Then comes Das Rollende Hotel. [A German invention seen on the road: A bus with a trailer that sleeps 39 people.] Thirty-nine cells in three layers. A heap of diarrhoea 3 yards from the entrance with a piece of toilet paper, attached like a flag.

It is assumed that because people enjoy themselves, what they are doing must be OK. People enjoy themselves in war. The hardships are what weakens their enjoyment. The trick is to get them to volunteer their money and themselves in the first place.

Great dust storm blows up – lasts for an hour. Then clear night.

Wednesday, 18th

To Kandahar. Lose Holst. Find Aria hotel. Comfortable. 25Afs. Lungful of Hookah hash smoke nearly kills me. Frenchman, hair in long black ringlets and black lace shirt with trim mustache and beard like decadent young blade of 18th Century. [He was fondling and polishing a brick of hash to smuggle through Iran and Turkey. I thought it better not to mention it in my notes. I always wondered whether he made it through, having seen “Midnight Express”]